Introduction

In the management literature, the debate, argument, and counter argument of the contribution of qualitative versus quantitative research is not abating. In particular, questioning continues on the manner in which the validity and generalisability of qualitative research is underpinned or undermined (Aguinis & Solarino, 2019; Pratt et al., 2019). Management accounting research is not immune to this debate with many scholars teasing out relevant aspects including: subjectivity, validity, rationale, appropriateness, and contribution (Ahrens, 2008; Chapman, 2008; Humphrey, 2014; Laughlin, 2004; Lillis, 2008; McKinnon, 1988; Parker, 2014; Vaivio, 2008). In this context providing illustrative examples of how qualitative research might be approached in a manner that addresses concerns of validity and fit is important (Taylor, 2018). This is especially so with interpretive research approaches such as abduction where replication may be viewed as problematic (Bamberger, 2019). Few papers, with the notable exception of Taylor (2018), draw from the experience of abductive research in management accounting. This paper adds to the development of our understanding of the challenges in abduction and the research practices that mitigate them.

This paper sets out the approach to a qualitative case study completed for the author’s PhD. The field work and analysis was conducted between 2015 and 2018 with some of the core findings published in 2018 (F. Conaty & Robbins, 2018). The paper elicits the way in which theory, data, and the researcher interact, the role of reflective practices, and the importance of maintaining an open, objective, analytical perspective.

The study’s objective was to explore how the management of Non-Profit Organisations (NPOs), providing health and welfare services, perceive the complex stakeholder profile of their organisations, and how their perception of stakeholder salience informs the design and use of Management Control Systems (MCS). The motivation in conducting this research was informed through the researcher’s personal experience in the domain of disability services in Ireland, coupled with a growing call for research to explicate the dynamics of performance management in NPOs involved in the provision of health, welfare, and other services (Bar-Nir & Gal, 2011; Barretta & Busco, 2011; F. J. Conaty, 2012; Stone & Ostrower, 2007).

The researcher’s 20-year experience with NPOs in the disability sector in Ireland spanned both personal and professional involvement in the formation and direction of intellectual disability support organisations at a national and regional level. This experience developed in the researcher an awareness that NPOs face differing and complex challenges, different from those experienced by for-profit and public sector organisations, fuelling an interest in the management of NPOs and the role of accounting and MCS in management practices.

The next section outlines the methodological approach of abduction in general, the specifics of why it was suitable for this case study, and the reasoning behind the selection of the initial theoretical frame. The detail of the approach in practice follows, from case selection, to pre-field work, data gathering, and analysis. At each stage the manner in which the abductive approach informed the design and conduct of the research is outlined. The key challenges for validity and generalisability are then summarised, followed by some further reflections on the experience of conducting abductive research. Finally the concluding section assembles a practical overview of abduction as an approach to research in management accounting.

Abduction: The Role of Theory, Phronesis and Reflection

In selecting the intellectual disability services sector in Ireland as the domain of study, the researcher’s twenty years experience in that domain needed to be recognised and managed (see section setting out the detail of the case selection). The challenge, therefore, was how to recognise and draw on this experience without undermining the integrity of the research. Abductive reasoning, first described by the American philosopher C.S. Peirce (Haig, 2005), recognises the role of the researcher through embracing their prior experience, phronesis[1], as an unavoidable and essential element in the analytical relational dynamic between researcher, the subject of study, and theory (Thomas, 2010). As a methodological approach, abduction presented the potential to meet the challenge of recognising the researcher’s experience in a manner that would not undermine but rather enhance the research.

In addition to the researcher’s experience of the domain of study suggesting the appropriateness of abduction, the approach was further underpinned by two additional factors. As described later, stakeholder theory provided the overarching initial theoretical frame for the research. Freeman (1999, p. 233, 236) argues that stakeholder theory is underpinned by a ‘philosophical pragmatism’ which resonates with the observation that ‘pragmatism’ is an essential feature lying at the heart of abductive research (Lukka & Modell, 2010, p. 466-467; Richardson & Kramer, 2006, p. 499). Furthermore, an abductive approach lends itself to case study research where the researcher is in close proximity to the phenomenon under study and the source of the data. Together, the researcher’s experience, the research question, the initial theoretical frame, and the case study method, underpinned abduction as a good fit for the study.

Abduction

An abductive, unlike a deductive approach, does not involve the pre-selection of a theory to be verified through the formulation and testing of hypotheses (Haig, 2005). Nor, as is the case with an inductive approach, is abduction concerned with building and justifying theory from analysing empirical data through ‘secure observations’ of singular events (Haig, 2005, p. 372-373). Rather, with abduction, hypotheses are developed from examining facts that infer; (i) that a new theory may have validity and can be accepted if no other explanation has greater validity, or (ii) that an existing theory may be further developed (Haig, 2005; Kapitan, 1992). Abduction is not necessarily an alternative to induction and deduction, but rather that each one may lend itself to different research objectives; deduction - theory testing, induction - theory development from data, abduction - generation of hypothesis from inference that suggest new, or existing theory development.

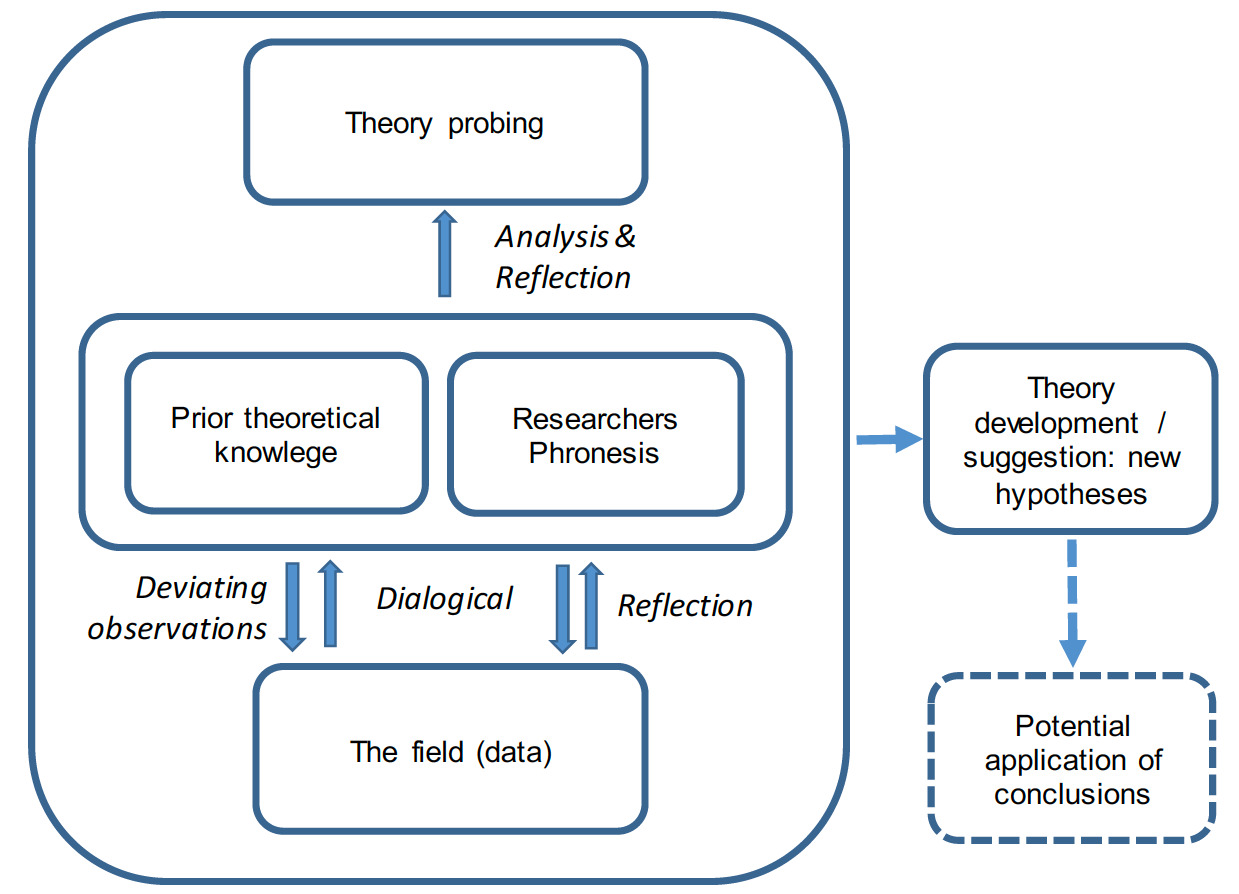

As an approach to research, abduction, as a means of inferring new theory or the development of existing theory, fits with the idea that ‘the practice of qualitative field studies involves an ongoing reflection on data and its positioning against different theories such that data can contribute to and develop further the chosen research questions’ (Ahrens & Chapman, 2006, p. 820). Lukka & Modell (2010, p. 467) draw a distinction between deduction and abduction observing that abduction ‘starts from the empirical findings, not from theory’, but that this ‘does not deny the role of prior theoretical knowledge in providing a background to the search for the most plausible explanation for empirical observations’ (Lukka & Modell, 2010, p. 467). The relational dynamics of the abductive approach are shown in Figure 1.

As noted above, the abductive approach may proceed with or without an initial theoretical frame. If an initial theoretical frame is accepted, it is not with a view to testing the theory, as in deduction, but rather to facilitate the exploration of the phenomena through a close examination of individual cases (Thomas, 2010). It is through such close examination that plausible inferences may be drawn, that in turn lead to the development of existing theory, or potentially suggest new theory entirely (Haig, 2005; Kapitan, 1992; Lukka & Modell, 2010; Thomas, 2010). Critically, the process involves a continuous reflective dialogue between the researcher, data, and theory (Haig, 2005; Thomas, 2010) (See Figure 1). This dialogue allows for novel and unanticipated themes to emerge as well as probing of the expected as an integral part of data gathering and analysis.

Abduction and the Role of Phronesis: A Dialogical Approach

The abductive approach allows for creativity and intuition to inform theoretical evolution and to understanding the generalisable and the specifics of the observed phenomena (Dubois & Gadde, 2002; Kovács & Spens, 2005). Indeed, it is through embracing the researcher’s phronesis as a means of interpretation, that the ability to dustinguish the generalisable and the specific is enabled. This, in turn, facilitates critical analysis allowing insights to emerge from the interplay of theory as an evolving heuristic guide, case, and researcher. Central to this process is the role of reflection. Drawing from the concept of ‘reflexive sociology’ as described by Bourdieu (1990, p. 9-14), reflective practices, incorporated within the abductive approach, are critical to positioning the researcher’s phronesis in the analytical process (Figure 1). Phronesis is the collective application of practical understanding, wisdom, prudence, and sound judgement. Notably, case studies, as in this study, offer ‘an example from which one’s experience, one’s phronesis, enables one to gather insight or understand a problem’ (Thomas, 2010, p. 578).

The primary research data for the case study, captured through semi-structured interviews with managers and informed by a branch of stakeholder theory, stakeholder salience theory, provided contextualised exemplars of managers perceptions of stakeholders and MCS. The data was gathered, analysed, and interpreted acknowledging the researcher’s phronesis. This process was continuous and integrated as opposed to purely sequential, allowing for the necessary dialogue between the researcher, data, and theory. By embracing the researcher’s experiential understanding in this way, the approach recognises the interplay of habitus and field[2] (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 9-14; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 15-19; Navarro, 2006, p. 16-18), as an underpinning dynamic of the abductive approach. In the practice of abductive social enquiry, Thomas (2010, p. 579) highlights the importance of intuitive ‘insight’ and that ‘the case study seems the ideal vehicle for this kind of insight to occur, as long as it is enabled by a spirit of inquisitiveness and not extinguished in a search for generality’. While ‘questioning is the starting point, serendipity, noticing, and insight provide an elevation, and interpretation based on phronesis’ that ‘is key’ to the approach (Thomas, 2010, p. 579).

Exploring the role of data and theory in qualitative research in management accounting, Ahrens & Chapman (2006, p. 837) argue that ‘to generate findings that are of interest to the wider management accounting research community, the qualitative field researcher must be able to continuously make linkages between theory and findings from the field in order to evaluate the potential interest of the research as it unfolds’. They continue that ‘this ongoing engaging of research questions, theory, and data has important implications for the ways in which qualitative field researchers can define the field and interpret its activities’. With abduction this dynamic is both varied and taken one step further. The variation is that an initial theoretical frame may or may not be part of this engagement, while the inclusion of the researcher’s phronesis further enriches the ongoing engagement and analytical dialogue. In the study described in this paper, an initial theory was incorporated.

The Initial Theoretical Frame

The NPO literature in the main characterises NPO performance as a construct of the objectives of multiple stakeholders (Herman & Renz, 1998). In conceptualising an approach to research into MCS (as employed by management in the management of performance) a multiple stakeholder conception of performance suggested that stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984, p. 1-249) might assist in framing an understanding of the dynamics at play, and for MCS design and use in particular (Balser & McClusky, 2005; Collier, 2008; Freeman & Phillips, 2002; McAdam et al., 2005). Further, accepting that what is perceived as important to management will attract the attention of management, suggested that the stakeholder salience framework as developed by Mitchell et al. (1997) could provide a useful initial framework in the examination of the dynamics of MCS design and use in NPOs. Stakeholder salience theory posits that management’s attention to the needs of any particular stakeholder depends on how salient they perceive the stakeholder to be. For the purposes of the study, stakeholder theory, and in particular, stakeholder salience theory was the initial theoretical frame.

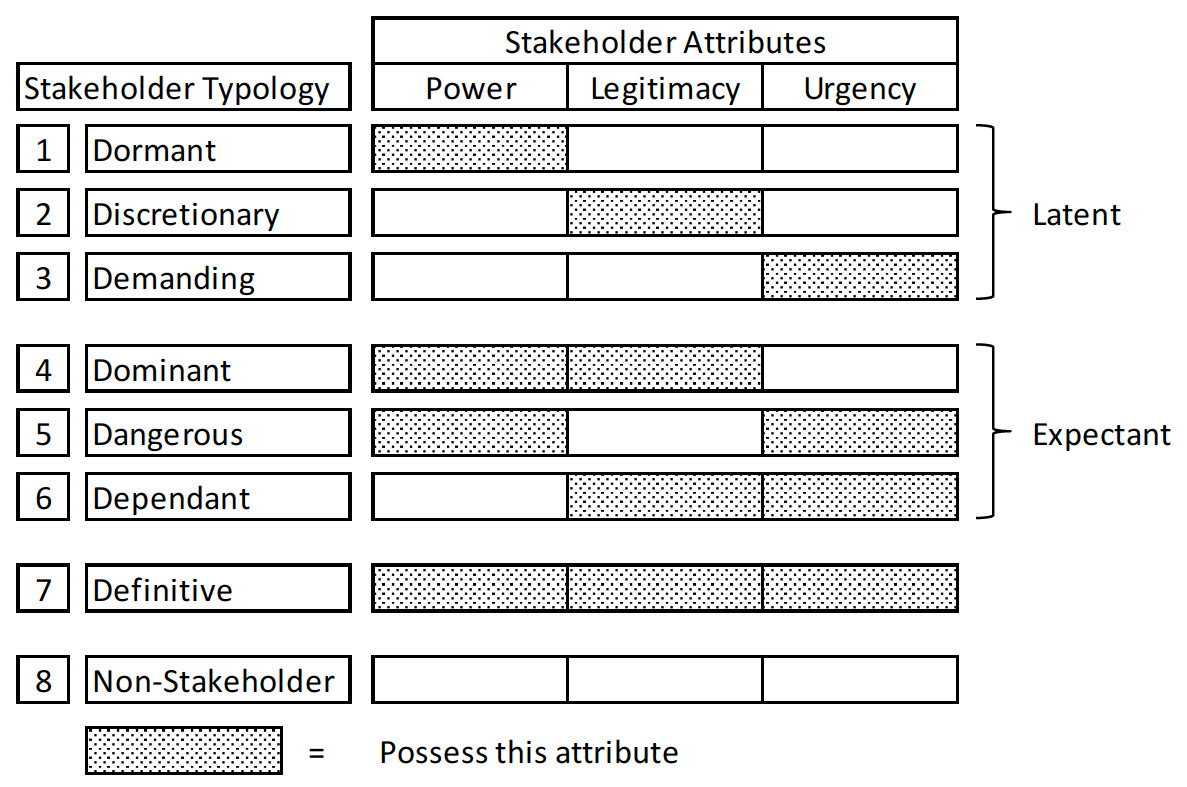

The fundamental underpinning principle of stakeholder salience theory is that management’s attention to individual or groups of stakeholders will be aligned to their perceptions of the salience of those stakeholders. From their synthesis of the literature and prior study, Mitchell et al. (1997), focus on the three attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency (of the stakeholder’s need or call on the organisation) as a means of identifying relevant stakeholders and describing differing stakeholder typologies. Mitchell et al. (1997, p. 862-863) propose what in their words is a ‘systematic comprehensible, and dynamic model’ of stakeholder identification. Their model holds that the attributes of power and legitimacy are the primary identifying attributes and that once ‘evaluated in light of the compelling demands of urgency’, management’s perception of stakeholder salience is revealed (Mitchell et al., 1997, p. 863). In identifying the differing combinations of attributes that a stakeholder may be perceived to possess, the model classifies stakeholders into seven categories or typologies (Mitchell et al., 1997, p. 872-879) (see Figure 2).

Mitchell et al. (1997, p. 878-879) identify stakeholders that possess all three attributes as ‘Definitive’, and that they would be afforded the greatest attention with management having ‘a clear and immediate mandate to attend to and give priority to them’. Stakeholders possessing two attributes are regarded as ‘expectant’ and, depending on the attributes they possess, are regarded as either ‘Dominant’, ‘Dangerous’, or ‘Dependent’ (see Figure 2). These stakeholders will command a significant level of attention with ‘the level of engagement between managers and these expectant stakeholders likely to be higher’ than less salient stakeholders possessing only one attribute (Mitchell et al., 1997, p. 876-878). Stakeholders perceived to be possessed of only one attribute are identified as: ‘Dormant’ when powerful; ‘Discretionary’ when legitimate; and ‘Demanding’ when urgent; collectively considered as ‘latent’ they would command relatively less attention, if any at all (Mitchell et al., 1997, p. 874-876).

Conduct of the Research: Case Study and Data Gathering

Case Study

Case study research resonates with abduction as a methodological approach as it supports a depth of interaction between the researcher and the field and between data and theory. Furthermore, as the abductive approach was informed by stakeholder salience theory, and centred on the analysis of management perceptions, a case study approach allowed for the necessary proximity to the field and data in addressing the research objectives. When the subjective perspective of organisational actors is central to the objectives of research, case studies are regarded as having significant utility, particularly when how or why questions are being posed, when the researcher has little control over events, and when the focus is on contemporary phenomenon in a real life context’ (Adams et al., 2006, p. 362). In this study, the combination of the abductive approach, the nature of the research questions, and case study as the approach to data gathering, reinforced each other.

Case Study and Abduction

There are differing forms of case study that lend themselves to differing research questions; for example, ‘exploratory’, ‘descriptive’, ‘illustrative’, and ‘explanatory or causal’ (Adams et al., 2006, p. 364). The research question addressed in the case study: How do management’s perceptions of stakeholder salience inform the design and use of MCS in NPOs?, could suggest that the case study is solely descriptive in nature. The how in the research question, however, embodied not just how but in combination with inform, embraced the implicit question of why or in what manner the salience perceptions of managers inform the design and use of MCS. In consequence, while having a descriptive element, the case study was also explanatory in nature; where the analysis sought not just to describe the stakeholder salience perceptions of managers and their perceptions of MCS design and use, but also the dynamics at play. In considering both how and why, through an abductive process, the research allowed for the potential for plausible explanations of the relational dynamics at play to emerge. Additionally, the nature of the phenomenon to be studied was a central factor in the study approach to be adopted, as was the manner in which the phenomenon might best be observed. Case studies, and in particular field studies, lend themselves to ‘studying issues that are not yet well understood, that are socially complex or contextually contingent’ (Ferreira & Merchant, 1992, p. 24). The immersive nature of abduction as a methodological approach facilitates such enquiry. Further, as noted earlier, reflection is a central aspect of the abductive approach and case study research facilitates reflection as the nature of case studies allow for the interaction of researcher, field, and contemplative space (Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006; Oliver et al., 2005).

The Research Question and Abduction

Understanding management perceptions of stakeholder salience, in an NPO performance context, was central to addressing the research question. The perceptions of management and organisational performance can be argued to be complex and socially embedded. In this regard an abductive approach to a case study facilitated the depth of phenomenological understanding required. In particular, the nuance necessary in embracing the researcher’s phronesis is, arguably, most effectively enabled through in-depth direct engagement with the actors who populate the situational domain of the phenomenon being studied. This level of direct engagement is best realised through a case study, something that was reinforced by the experience of this study.

Case Selection: Meeting the Needs of the Research and the Abductive Approach

Given the objectives of the research, the choice of case organisations to select presented a challenge. Important considerations were access, spread, and representation. Yin (1999, p. 1214) underscores an approach to case selection from theoretical grounds, observing that ‘the preliminary theoretical propositions used in formulating the case study design provide important guidance for defining the case’. The objective of the study was to examine the role of management stakeholder perceptions in the design and use of MCS in NPOs engaged in the provision of public health and welfare services. In case selection what was needed was a substantive exemplar to provide ‘clear examples of new relationships, new orientations, or new phenomena that current theory and theoretical perspectives have not captured’ (Dyer & Wilkins, 1991, p. 617). The intellectual disability services sector in Ireland was the obvious choice as an exemplar of the domain of study given the researcher’s familiarity with the sector. Not only did this facilitate access to relevant organisations, but critically, drew on the researcher’s phronesis as an integral part of the abductive process. Additionally, with the sector representing 13.4% of all Government expenditure in the provision of such services (Campbell et al., 2017), it is a substantive exemplar.

Furthermore, the nature of the research called for a ‘paradigmatic’ approach to selection as described by Flyvbjerg (2006, p. 232-233). Paradigmatic cases ‘highlight more general characteristics of the societies in question’ (that are the subject of study), the selection of which is both intuitive and informed by understanding with a view to providing both ‘metaphorical’ and ‘prototypical’ value (Flyvbjerg, 2006, p. 232). The intellectual disability services’ sector in Ireland is dominated by just over 60 NPOs delivering in excess of 85% of all such services. It was evident therefore that a selection of substantive NPOs from the sector with a spread in terms of organisational origin, secular (S) and religious (R), and that had a breadth of service delivery,[3] were required to meet the paradigmatic requirements. Four substantive NPOs were included in the case study (Table 1).

With 3,525 people in receipt of services from these four NPOs, including residential, respite, and day services, the organisations at that time accounted for c.12.7% of the intellectual disability services delivered by NPOs in Ireland. While there is no upper limit as to a suitable representative proportion of organisations in a particular domain in qualitative research, the operational coverage of these four NPOs was such as to provide confidence in meeting the paradigmatic requirements for the field of study. In so doing, however, the selection was not so extensive as to detract from an ability to achieve the depth of understanding sought through the abductive approach.

Phronesis and the Development of Sectoral Knowledge and Understanding

Phronesis built from experience, the accumulation of knowledge, and the development of understanding, is central to the abductive approach. As previously outlined the researcher has over twenty years of involvement with the intellectual disability sector in Ireland, ranging from ad-hoc participation in community organisations to national policy development. This involvement with the sector included board membership on both regional NPO disability service organisations and national advocacy support organisations over many years. In addition to experientially derived knowledge and understanding, relevant national policy documents, statutes, and international treaties in relation to disability published over the last fifteen years were studied for further context.

To build on his sectoral knowledge, and in tandem with conducting a deep and structured literature review, the researcher sought advance access to one of the NPOs identified for the case study for a preliminary field visit (Table 1 - S1). The purpose of the site visit was to advance knowledge and understanding of performance management systems, MCS, and governance structures, and to obtain preliminary insights into management perceptions of their organisation mission and of stakeholder objectives in that context. This immersion further enriched the researcher’s existing phronesis that he was to subsequently bring into the data-gathering and analysis process of the study.

Primary Data Collection: Meeting the Needs of the Research Objectives and the Abductive Approach

Drawing on the work of Hyndman & McDonnell (2009) on NPO governance structures, four relevant external stakeholders were selected for the study: 1) the ‘Funder’ (the State, through the Health Service Executive (HSE)[4]); 2) the primary ‘Regulator’ (Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA)[5]); 3) the client ‘service users’; and 4) the NPO ‘Board’. The primary data was collected through semi-structured interviews with 36 members of the management teams of the four NPOs between May 2015 and May 2016. Each NPO was requested to make available all senior managers and as many middle and unit-level managers as might be available during the periods of the site visits. At senior level, managers with a direct ‘service’ function and those in ‘support’ function roles were included, all other managers were involved in direct service delivery. This allowed for a breadth and depth of views across the management teams, see Table 2.

In addition to the interviews, knowledge and understanding of each organisation was augmented through review of mission statements, strategic plans, organisational charts and annual reports covering both operational and financial activities. Finally, arising from the nature of a field-based case study, additional informal encounters with managers and other staff featured in the visits to all of the NPOs. These encounters complemented the researcher’s phronesis, augmenting his knowledge and understanding of the organisations and facilitating additional nuanced dialogue between the researcher and the data, a dialogue central to the abductive approach.

Interview Design: Addressing the Research Question, Facilitating Abduction and Mitigating Bias

The interviews were semi-structured and informed both by the abductive approach (allowing for dialogue and facilitating insight) and the initial theoretical frame, stakeholder salience theory. The flexibility of the semi-structured interview approach allowed the interviews to flow, facilitating the emergence and exploration of themes that could be further probed during the data analysis. An interview guide was employed, developed from the experiences of the preliminary field visit and informed by the initial theoretical frame. This ensured that themes central to the research were fully explored. The interview guide was refined after the first six interviews drawing on the initial experience of the conduct of the interviews, their flow, and focus. Firstly, to facilitate understanding on the part of interviewees of the salience attributes, in particular urgency, vignettes were incorporated to set up scenarios for the interviewees to respond to. Secondly, the sequencing of the questions was reordered to facilitate a better flow to the interview. Thirdly, invitations for the interviewees to reflect were including in the interview design. The latter arose as a result of some of the initial interviewees spontaneously engaging in reflection, yielding valuable additional insight, underpinning reflection as part of the abductive process (see section following on reflection and the interview process). Table 3 sets out an extract from the interview guide in relation to the exploration of the salience attribute urgency.

As well as ensuring the interviews were effectively designed and conducted to reflect the objectives of the research, it was critical to mitigate bias. Given the researcher’s phronesis, a constant self-awareness and vigilance to avoid bias featured in the conduct of the interviews. Further, and crucially, during the conduct of the interviews appropriate time was incorporated to facilitate interviewee/researcher interaction, to draw on the insights of the interviewees, and to allow for reflection (Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006; McKinnon, 1988; Oliver et al., 2005; Yin, 1999).

The choice of interviewees is also seen as contributing to mitigating bias. Eisenhardt & Graebner (2007, p. 28) suggest that a ‘key approach’ in managing bias is to include ‘numerous and highly knowledgeable informants who view the focal phenomena from diverse perspectives’ and that ‘these informants can include organisational actors from different hierarchical levels, functional areas, groups, and geographies, as well as actors from other relevant organisations’. The mix of managers interviewed in the study spanned differing management levels and functions, and were drawn from both religious and secular organisations. This tactic, in managing the potential for bias and underpinning the validity of the research, was augmented through adopting additional measures such as note taking, probing questions, and the researcher’s self-awareness of his own social behaviour in the field (McKinnon, 1988). Measures that also support a dialogical abductive approach.

The interviews were conducted in a manner that allowed time for the exploration of emergent themes in keeping with the abductive approach. Central to this was the researcher’s understanding of the sector, that sensitised him to that which might be relevant. Phronesis played a central role in the identification and probing of important themes, such as stakeholder advocacy and accountability, and in discarding others that presented, such as the role of humility, that on reflection was not germane to addressing the research question. The researcher’s familiarity with the domain of study was disclosed to and accepted by the interviewees. This disclosure was central to ensuring an openness and frankness of response by the interviewees who may otherwise have held back. Additionally, by embracing his phronesis, the researcher was able to recognise responses that were promoting a particular agenda, or interviewee bias.

Reflection and the Interview Approach

As set out earlier, reflection is central to the abductive approach and supports the development of insight that might not otherwise emerge (Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006; Oliver et al., 2005). Time for reflection both during, as well as at the conclusion of each interview was factored into the research design. At the end of each interview managers were encouraged to pause and ponder, and several important themes emerged from these reflections, or indeed themes that had emerged earlier during the course of an interview were further reinforced. These reflections fed into the process of working with and analysing the data as described below.

Analysing the Data

The data analysis was a continuous process commencing with the reading of background and contextual documentation (relevant external policy documents and statutes, internal governance policies, and systems documentation for each of the MCS elements) and then moving to the recorded interview transcripts and notes. Key elements of the data analysis process were central in underpinning the abductive process and are explored below.

Coding and Initial Analysis of Interview Data

Interviews were recorded and listened back to before being transcribed. Note taking, during, after, and when listening to the recorded interviews was an important aspect of the analysis, capturing relevant themes and observations. Pause and reflection, and listening to the tone and emphasis of interviewees throughout the interviews formed an integral part to facilitate as deep and as analytical a process as possible (Oliver et al., 2005).

Field research by its nature can be overwhelming, as observed by Ahrens & Dent (1998, p. 9), ‘a recurrent fear […] is the possibility of “drowning in the data”.’ Structured coding can provide a life raft to help in avoiding drowning while unstructured coding can effectively abandon the researcher to an ocean of data devoid of meaning. Coding and analysis of the interviews was managed using the qualitative data analysis software package, NVivo. This facilitated order and organisation and assisted in the identification and further probing of relevant themes as they emerged.

The approach to coding was initially structured around the essential areas of exploration to address the research question: 1) stakeholder objectives, 2) stakeholder salience attributes of power, legitimacy, and urgency, 3) stakeholder importance in an organisational mission context, 4) MCS utility for management in meeting stakeholder objectives, and 5) MCS design and use. These areas of exploration were the first high-order coding nodes utilised in the first review of the interview data. This, together with insights gained from prior literature, the preliminary field study, background and contextual documentation, internal governance and systems documentation (MCS), and crucially the researcher’s phronesis, facilitated identifying emerging themes from the data. These emerging themes were located both within the initial high-order coding nodes, requiring the inclusion of sub-nodes, and outside these nodes requiring the inclusion of additional coding nodes. This process continued through four, and in some instances five reviews of the interview data. The process involved a continuous journey for the researcher moving from theory to data in a series of trips to and fro, compelled by emerging insights and observations, towards a formulation of an understanding of plausible inferences. Central to this process was reflection on the part of the researcher. This was reinforced once again through note taking and the maintenance of a thought board (see section to follow on facilitating a dialogical approach).

Emerging Themes

The interviews were informed by honest and open cooperation of interviewees supporting the capture of a deep and rich body of data. The emergence of a coherent story from such data requires nurturing and also honesty from the researcher, as Ahrens & Dent (1998, p. 9) observe, ‘the researcher examines and re-examines existing observations and gathers more field material, to ensure that the patterns adequately represent the observed world and are not merely a product of his or her imagination; […] seeing patterns and developing theory is an emergent process in field research, in which the researcher iterates between insights and the field material’.

During this research, and in particular during the coding and analysis phase, several themes emerged that were later discounted in terms of addressing the central research question. Potential emerging themes were rejected if, after further analysis, and reflection, informed by the researcher’s phronesis, they were not adequately supported by the data through the identification of corroborating patterns that underpinned a coherent story. Conversely, emerging themes were retained for further consideration if the data analysis suggested patterns that corroborated a coherent explanatory story. This openness to the consideration of emergent themes, including discarding them, is critical in underpinning the integrity of the research and ultimately the findings (Ahrens & Dent, 1998).

Stakeholder advocacy and accountability emerged as two distinct and important themes. The emergence of advocacy in relation to the service users, was a powerful example of how this process surfaced an unexpected theme. Advocacy first emerged through the regular mention by interviewees when referring to service users, of their voice, or lack thereof, and was often noted in the reflective part of the interview. Advocacy was not something that was suggested as being relevant by the initial theoretical frame and emerged solely from the data. The consistency of interviewee reference to advocacy (with identifying phrases such as advocacy, voice, being heard, excluded/included, etc), combined with the researcher’s phronesis (that through reflection underpinned the validity of advocacy as a central element of the phenomenon under study), led to further exploration of the role of advocacy in MCS design and use. Ultimately, advocacy formed a central finding of the research, suggesting a nuanced approach to understanding perceptions of salience and its role in MCS design and use in NPOs engaged with service users.

Facilitating a Dialogical Approach

A dialogical approach informed by insight and underpinned by the researcher’s phronesis, is central to abduction. A dialogical approach requires a mindful and reflective disposition to probing and questioning the validity of explanation. Bazeley (2013, p. 101-124) outlines the steps of ‘read, reflect, play and explore’, that describe the process undertaken in the study. While not unique to an abductive approach, these activities in analysing the data, support a rich dialogical and reflective practice that is essential to the abductive process. Through engaging with, and spending time with, the data in this manner, differing perspectives can be considered, surfacing potential inference for consideration as having validity. Critically, engaging with the data in this way allows the space and time for the researcher’s phronesis to inform the analysis.

Read: Reading was central to the analysis at every step; commencing with the reading of the relevant literature and the background and contextual documents, to reading and re-reading the interview transcripts. Initial reading of the transcripts was conducted while listening to the interview recordings. This facilitated understanding, nuance, and inflection and also controlled for interpretation errors in the transcription process. During the preliminary field work, the background and contextual documentation in the area of governance and MCS was supplemented with discussions with relevant managers. These discussions were recorded by note taking and later, with the addition of the information from the systems documentation, transcribed into descriptions of the primary MCS.

Reflect: Essential to the abductive methodology, reflection on the part of the researcher characterised the analytical process. Reflective notes were written while listening to the interview recording, during the coding process, and through to the formulation of the distinctive story line of the research. Further, these notes were used to collate observed areas of interest, possible avenues for exploration as well as, consensus and conflicts with prior literature and theory. Challenges encountered were brought to supervision meetings and research fora which were used to tease out and understand the observations in the context of the research objective. The latter element of the research process, supervision and engaging with appropriate research fora, represented an extension of the reflective process, offering insight and an opportunity to engage with alternative objective views. This helped to redirect in instances where the researcher may have strayed from the primary research objective (an acknowledged risk when presented with a rich data base (Ahrens & Dent, 1998; Bazeley, 2013, p. 63-91)), and provided a source of confirmation when an understanding was shared and a consensus reflected back.

Play: Play is an unusual term, but is used by Bazeley (2013, p. 106-112), to describe processes where data is taken and framed in differing ways (pictures, diagrams, writing vignettes, video, etc.) to promote insight and facilitate an emergent understanding. Freeform diagrammatic rendering as an approach was employed as part of the analysis from the outset. Early in the analytical process a free-form thought board was constructed. The thought board was maintained and regularly updated throughout the analysis phase of the research. The board assisted in capturing observations and emergent themes, their relation to theory, and the interrelationships in particular with the nature and design of MCS. The thought board proved to be a useful methodology in informing the ongoing coding process, allowing for the role of phronesis, and the filtering of themes.

Explore: The use of reflective note taking and the maintenance of the thought board, combined with the coding process itself, allowed for a rich exploration of the data. As observed by Bazeley (2013, p. 113) ‘analysis is as much about identifying the larger significance and meaning of objects and events for a participant, about finding the connections – the interdependencies – within and across data, as it is about segmenting and coding data’. While coding was essential in facilitating the emergence of themes and relevant ‘story lines’, the broader perspective engaged in through reflection, note taking, and the maintenance of the thought board, underpinned the coherence of the emerging story and helped to ensure that the story remained connected with reality as opposed to simply being a construction of the coding process.

Two Key Challenges and Trade-Offs of the Abductive Approach

While not unique to abductive research, the management of bias and underpinning validity present particular challenges for abductive research, as does the further challenge of generalisability. Both of these aspects are reflected on below.

Phronesis and Research Validity

In addition to the challenges of generalisability of interpretivist research, addressed in the next section, abductive research comes with the added challenge of researchers embracing their own phronesis in interpreting the observed and drawing inference from the data. When it comes to case study research adopting an abductive approach, validity is not obtained from an existing body of theory or accepted generalised knowledge but ‘through the connections and insights it offers between another’s experience and one’s own’, between the researcher and the researched (Thomas, 2010, p. 579). This is cited as a potential weaknesses of abductive research, leading to the potential for the ‘logical fallacy of affirming the consequent’ giving rise to a difficulty in determining whether some theoretical explanations have a greater value than others (Lukka & Modell, 2010, p. 467). To address this, abduction is recognised as ‘an ongoing process compelling researchers to constantly remain open to alternative explanations whilst ruling out explanations deemed less plausible as they move back and forth between theory and empirical data’ (Lukka & Modell, 2010, p. 467-468). The key methods employed in the conduct of the study to guard against the risk of bias, while embracing the phronesis of the researcher, were: attention to detail in the approach to the study design; approach to data gathering; the analytical approach as described earlier, and crucially the researcher’s approach to self awareness (see later section on the researcher and the observer self). These methods involved key aspects such as case and interviewee selection, constant vigilance in the conduct of the interviews, identification and rejection or acceptance of emergent themes, and the constant challenging of inferences derived. Further, the manner in which the researcher approached the dialogical analytical process, structured the interaction with the data, made use of the thought board, and the multiple readings of the data, underpinned analytical thoroughness while at the same time allowing the researcher’s phronesis to probe the emerging storylines. The deliberate inclusion of reflective practice on the part of the researcher, and indeed the interviewee participants, in the conduct of the research was central to the process of internal validation. It is through such a structured approach, with reflection, and self awareness, that the phronesis of the researcher can be drawn on to sense test inferences drawn. All of these measures were further reinforced through the regular testing of the observations and inferences in open, objective, research fora.

The Challenge for Generalisability

With an abductive approach to case study research, the importance of embracing the researcher’s phronesis, to facilitate depth and insight is critical, while at the same time ensuring that the case selection is otherwise appropriate for the research objectives. This required the selection of a substantive paradigmatic exemplar while allowing for the depth of insight central to abduction. The reasoning behind the consequent selection of the intellectual disability sector in Ireland is described earlier in outlining the conduct of the research (see earlier section on case selection). As a substantive exemplar of NPOs in the health and welfare service area, the validity and generalisability of the research outcomes for such organisations is underpinned. It is nevertheless accepted that as the sector is a subset of NPOs involved in health and welfare services, thus future generalisability to sectors other than the intellectual disability and similar sectors is bounded.

Studies crafted around a single qualitative case study (in this study the intellectual disability sector in Ireland), while facilitating phronesis and depth of understanding of phenomena, given its singularity is open to criticism for a lack of generalisability. This criticism is not unique to abductive research but is a well-recognised criticism of interpretivist case based research in general (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007; Flyvbjerg, 2006; McKinnon, 1988; Parker & Northcott, 2016; Siggelkow, 2007; Yin, 1999). Such criticisms are, however, cited as a particular challenge in abductive research with recognition of an inevitable trade-off between the depth and richness of understanding and generalisability (Dubois & Gadde, 2002; Kovács & Spens, 2005; Thomas, 2010). The objective of abduction is to gain a depth of understanding of the phenomenon of study in a domain and, where appropriate, in the context of existing theory. Through the design and conduct of this study, this depth was achieved and, as reflected on in the next section, the research has supported an argument for theory development and potential new, or hybrid, theory. While it is acknowledged that generalisability of findings from a study grounded in a specific domain presents challenges for future research, there are, nevertheless, perspectives that provide possible pathways of understanding the nature of the generalisability of the findings from such studies. Ahrens & Chapman (2006, p. 836) noted that ‘by showing the relationship between qualitative field study observations, area of scholarly debate (literature), and theory, the observation and analysis of organisational process can be structured in ways that can produce theoretically significant contributions,’ and because they remain grounded in their specific contexts, single qualitative field studies can be of general interest; and further, that ‘the specificity of theorising in qualitative field studies is one of their key characteristics and strengths.’ Furthermore, it is notable that the design, conduct, and findings of this study can be regarded as having both ‘theoretical generalisation’ and ‘naturalistic generalisation’ as described by Parker & Northcott (2016). The former, in the context of the theoretical analysis and findings, and the latter in the context of the depth and richness of the case study where ‘thick description plays a key role in building contextually situated research findings that support naturalistic generalisation by allowing the reader to draw appropriate comparisons’ (Parker & Northcott, 2016, p. 1114). It is from this understanding of scholarly value that the research seeks to contribute to both theory and practice. If this results in a certain trade off with, or qualification of, generalisability, this is accepted as an inevitable characteristic of abductive research.

Methodology and Research Outcomes: Some Reflections

Engaging in research through an abductive process positions the researcher within the process in a manner unlike other approaches; in particular the way in which the researcher embraces and deploys his or her phronesis. Another important consideration is the manner in which the approach in this study facilitated the exploration of the research question. Finally, central to abduction, understanding the manner in which the approach yielded theoretical outcomes is important to the practice of abductive research. These three elements are reflected on below.

The Researcher and the Observer’s Self

Adopting an abductive approach to the research allowed the researcher to be free to move from the initial theoretical frame of stakeholder salience theory, to allow the data and the interactive abductive approach to present plausible inferences. The plausible nature of those inferences was underpinned by permitting, with care, the researcher’s experience of the domain of study (phronesis) to be part of the sense testing of the suggested inference, and indeed to reveal what might not have otherwise emerged. Embracing the interplay of habitus and field[6] (Bourdieu, 1990, p. 9-14; Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992, p. 15-19) in this way necessitates an attuned self awareness. The approach requires the researcher to be self aware of a duality of identity: the researcher/observer and the ‘observer’s self’ (Krieger, 1985, p. 309). It is as if there are three parties to the research process: the researcher/observer, the observed, and the researcher/observer’s self. Krieger (1985, p. 320) pointed out that ‘the great danger of doing injustice to the reality of the [observed] does not come about through use of the self, but through lack of use of a full enough sense of self which, concomitantly, produces a stifled, artificial, limited, and unreal knowledge of others’. The challenge is not dissimilar to the need for awareness of the tension that is observed in participant observation research between ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ perspectives (Labaree, 2002, p. 115-118; McKinnon, 1988, p. 47-49). The need to be one’s own critical observer, to facilitate and at the same time police one’s phronesis, forced the researcher to be at all times self aware and probing, to identify and understand the implications of personal prejudice and bias. At every stage of the research process (case selection, interviewee selection, the conduct of the interviews, and the approach to analysis), this required the researcher to constantly challenge himself. It can be likened to sitting on a high shelf in your own mind from where you observe your active self, allowing you to question your actions, and conclusions. This was further reinforced by regular presentation and discussion of the work in independent fora, compelling the researcher to continuously question his role in the observations and analysis.

Abduction and the Research Findings

The abductive approach to the study facilitated the emergence of unanticipated themes and consideration of those themes as to their validity in addressing the research question. While several themes were ultimately discarded, two unanticipated themes emerged that retained their validity; underpinned by the rigour and probing of the analysis. The first, was advocacy as a support intervention, and the second was the discharge of accountability to stakeholders as an important element of MCS design and use. Consequently, both of these themes were explored through the relevant literature and helped to inform the analytical discussion providing insight that framed the key findings that emerged from the research. As noted earlier, while the abductive approach may not have been the sole driver of these insights and findings, it was undoubtedly a significant one.

Abduction and Theory

While abductive research may uses an initial theoretical frame, in this study stakeholder salience theory, the approach seeks through an iterative conversation, a dialogue, between the data the researcher and the initial theoretical frame, to draw plausible inferences that may suggest theory development or indeed new theory. In this study, both theory development and the possibility of new theory development were outcomes.

In terms of theory development, a key finding was a suggested refinement of stakeholder salience theory, adding the recognition that stakeholders may be regarded simultaneously possessing/not possessing a salience attribute and therefore also falling into differing stakeholder typologies simultaneously. This heretofore unarticulated nuance of the co-existence or duality of stakeholder typologies for a given stakeholder at a point in time contributes to the development of theory. The finding refines our understanding of stakeholder salience highlighting a much more complex interplay of perceptions and contexts and makes the case for the incorporation of this refinement into stakeholder salience theory (F. Conaty & Robbins, 2018).

Further, the analysis and findings were enriched through the recognition that another stakeholder theory, stakeholder-agency theory (Hill & Jones, 1992),[7] extended the depth of understanding gained through the lens of stakeholder salience theory. That stakeholder agency theory might facilitate such an extension was only evident as a result of the immersive abductive approach and, in particular, drawing on the phronesis of the researcher. The researcher’s practical knowledge of the dynamics of NPO stakeholder - management relations prompted the initial insight that suggested probing stakeholder - management agency dynamics. Stakeholder-agency theory in concert with the initial theoretical frame, helped to unlock further insights, in particular, in the description of agency interventions and moral hazard. This openness to additional theories as useful in framing an understanding of the phenomena of study, toward the evolution of theory or new theory development, was supported by the methodological approach of abduction (Lukka & Modell, 2010; Richardson & Kramer, 2006). This is something for researchers to be sensitive to in case study research when ‘events in the field may be best explained with reference to multiple theories’ (Ahrens & Chapman, 2006, p. 823). Openness to incorporating other theoretical frames that emerge as useful in the study of the phenomenon being observed, is a feature of abductive research that, as in this case, can provide valuable research outcomes in terms of theory development. The study described how the elucidation of stakeholder salience dynamics facilitated the inclusion of stakeholder agency theory as an additional frame of analysis – a symbiosis with stakeholder salience theory that might be described as a hybrid theory. This outcome supports the potential value for the pursuit of research that is open to embracing theoretical symbiosis.

Conclusions

The abductive approach and the research methods adopted presented challenges and opportunities in the conduct of this research. The manner in which these challenges were met, and the opportunities the study presented for developing methodological understanding, contribute significantly to the conduct of qualitative case study research in management accounting. In particular, the insights gleaned in meeting the challenge of recognising the observer’s self may prove useful to those who pursue abductive research.

Interpretive qualitative research persistently faces challenges as to the validity, meaning, and generalisability of findings. Interpretative management accounting research is not immune to or isolated from such critique (Ahrens, 2008; Ahrens & Chapman, 2006; Lukka & Modell, 2010). The abductive approach has come under even greater scrutiny in this regard (Haig, 2005; Lukka & Modell, 2010; Thomas, 2010). The conduct of this study exemplifies how validity and meaning can be underpinned, and generalisability trade-offs understood, through careful planning and conduct of research in terms of method. As an exemplar that directly addresses these critical challenges to interpretative qualitative research, the study provides a valuable methodological roadmap, reinforcing the contribution of the abductive approach to the conduct of research, not just in management accounting, but in general.

Central to underpinning the validity of the findings was managing the potential for bias and ensuring that the findings were led by, and grounded in, the data while allowing for depth of insight through embracing the researcher’s phronesis. In embracing the researcher’s phronesis, integrity of approach and method is vital. This was achieved in the awareness of, and attention afforded to, the challenges posed in the application of the abductive method. In particular, facilitating an iterative dialogue between the researcher’s phronesis, the data, the initial theoretical frame, and the literature while at the same time maintaining a critical awareness of the observer’s self. From the outset the role of reflective practices was recognised as an essential element in both supporting richness of exploration and rigour of analysis (Irvine & Gaffikin, 2006; Lukka & Modell, 2010; Oliver et al., 2005). In abductive research, but also in other interpretative approaches, thoroughness in self scrutiny and honesty is essential if validity is not to be compromised (Eisenhardt & Graebner, 2007). To this end the rigorous approach adopted in this study to the design and conduct of the interviews (including reflective practices) and to the analysis of the data (incorporating dialogue, reflection, creativity, and exposure to the objective criticism of other researchers) are suggested as exemplars of good practice in abductive research. The approaches adopted in allowing for the role of the researcher’s phronesis, while maintaining the necessary awareness of the observer’s self, are ultimately what underpin the validity of the findings.

Limitations, however, must be acknowledged. Notwithstanding the significant and positive contribution that the phronesis of the researcher brought in terms of access, execution, and analysis, and the approaches adopted to mitigate bias, the potential for residual bias must be recognised. This is accepted as an unavoidable risk in abductive research.

Further, it is also recognised that the account presented in this paper is incomplete, largely due to the practicalities of meeting the length constraints for published work. Nevertheless every effort was made to ensure a balanced representation of the research experience and approach adopted.

In describing an illustrative example of abduction as a methodological approach to qualitative research in management accounting, this paper advances the conversation surrounding the challenges of qualitative research, suggesting elements that underpin the validity and generalisability of abductive interpretative research. Other researchers may be prompted to share their experiences to build our collective understanding and trust in qualitative research.

Philosophy: practical understanding; wisdom, prudence; sound judgement, available at: (https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/phronesis) [Accessed on 28 January 2019].

Pierre Bourdieu described ‘habitus’ as that which is created through social process leading to patterns that are enduring and transferrable from one context to another; and ‘field’ as a network, structure or set of relationships which may be intellectual, religious, educational, cultural, etc. (Navarro, 2006, p. 16-18).

Support services for people with intellectual disability services range from day support services (typically multidisciplinary in nature) delivered in the community and in campus and school settings, residential services provided in community and institutional settings, and respite services again in either community or institutional settings. For a full profile of intellectual disability support services see: Annual Report of the National Intellectual Disability Database Committee 2017. Available at: https://www.hrb.ie/publications/publication/annual-report-of-the-national-intellectual-disability-database-committee-2017/ [Accessed on: 17 December 2018].

The Health Service Executive (HSE) is the primary public body in Ireland responsible for the commissioning, delivery, and oversight of acute and community health services.

The Health Information and Quality Authority (HIQA), is an independent authority established to drive high-quality and safe care for people using health and social care services in Ireland. see: https://www.hiqa.ie/ [Accessed on: 22 September 2018].

Pierre Bourdieu described ‘habitus’ as that which is created through social process leading to patterns that are enduring and transferrable from one context to another; and ‘field’ as a network, structure or set of relationships which may be intellectual, religious, educational, cultural, etc. (Navarro, 2006, p. 16-18).

Stakeholder Agency Theory was first described by Hill & Jones (1992). The theory places the management at the nexus of all relevant stakeholder relationships and posits that each management/stakeholder relationship can be viewed as an ‘agent/principal’ relationship with all of the attendant complexities of divergent interests, information differentials, moral hazard and self-interest. The authors modified the informing theories, agency theory and stakeholder theory, through the incorporation of aspects of theories of power and resource dependence.