Introduction

The current paper addresses an issue often overlooked in mainstream accounting history literature: the human need to render an account of our lives at death and the implications of this need for accounting. This idea relates to ‘eschatology’, a term that refers to religious or philosophical beliefs concerning death, judgement, and the ultimate destiny of the soul or humankind (Marinis, 2016; Segal, 2004). In this context, eschatological thinking frames the end of life as a time when one’s deeds are reviewed, weighed, and recorded, often with consequences for the afterlife. This phenomenon is significant as it speaks to a universal human concern: how we are judged based on our actions and moral worth throughout our lives. The belief in an essential ‘calling to account’ at life’s end, evident in historical writings spanning over 4,000 years (Marinis, 2016), reflects deep cultural and ethical roots that continue to influence contemporary norms. Religious traditions as diverse as those in ancient Egypt and early medieval Ireland—where Christian eschatological imagery appeared prominently in monastic stone carvings and hagiographic narratives—reveal how the notion of judgement after death was both spiritually formative and culturally embedded.

Evidence can be found in ancient Egyptian practices (Ezzamel, 2009), where the weighing of deeds determined one’s afterlife, and in early Judaic texts (Kuck, 1992) that shaped later Christian beliefs (Griffiths, 1991). Zoroastrianism, one of the world’s oldest monotheistic religions, also introduced powerful themes of personal judgement and moral dualism over 3,000 years ago, influencing Judaic and subsequently Christian eschatological thought (Clark, 1998). These themes were subsequently adopted and incorporated within Western religious traditions and art, especially in Celtic and medieval Ireland.

The early Irish church is known for several influential practices such as peregrinatio (Charles-Edwards, 1976; Meeder, 2019), the origins of penance (Aho, 2005; Dooley, 1982) and the hagiography of sea-going saints, such as St. Brendan (Wooding, 2000). The monastic influence of the Irish in Europe during the 6th and 7th centuries CE,[1] is evident in the founding of important monasteries such as Iona in Scotland, Lindisfarne in England, Fointaine in France and Bobbio in Italy (Bradley, 2003; H. Graham, 1925). What is possibly less well known, but of interest for this paper, is the imagery associated with judgement at death in stone carvings in early medieval Irish monasteries, providing an example of how eschatological imagery was embedded in Christian culture (Veelenturf, 1997). For instance, following the 8th century Céile Dé reform movement, several Irish high crosses of the 9th and 10th centuries CE depict scenes of the Last Judgement and the weighing of souls (Bradley, 2003; Veelenturf, 2017). These visual narratives helped reinforce the practice of rendering an account as central to the Christian life.

This body of research illustrates a persistent theme of moral evaluation that transcends individual cultures and epochs, prompting a deeper inquiry into its implications for modern accounting. The judgement or auditing of the self at the point of death was initially premised on the idea of an afterlife (Segal, 2004). However, the practical aspects of judging, and the literal writing down of an account in a book of deeds,[2] found in the early writings, gave way over time, to a self-regulating code of behaviour against which an individual would measure their moral worth with respect to contemporary social norms. This evaluation was often achieved through the intercession of a privileged group who were experts in the code and who could advise on the rendering of an account. The current paper presents an exploration of how accounting practice may have been influenced by this assessment of what happens at death, via the concept of ‘weighed in the balance’. An historical overview of the eschatological themes of (i) weighing, (ii) the book of deeds in which good and bad deeds are recorded, and (iii) the mediators or intercessors, demonstrates how the ‘rendering of an account’ became normalised over a long period of time as an often-unremarked backdrop to more recent social developments such as accounting. The current paper discusses the role played by eschatological imagery in a number of religious traditions, including that of Celtic monasticism in “early medieval Ireland” (Veelenturf, 2017, p. 222) in this process.

Despite the rich historical background in this area, there remains a notable gap in the literature regarding how past eschatological themes may have informed current accounting practices. Previous studies about the impact of religion on accounting have focused primarily on transactional phenomena within medical contexts or limited themselves to specific religious institutions (Baker, 2016; W. J. Jackson et al., 2013; Moerman & van der Laan, 2022). Cordery (2015) highlights the scarcity of macro-perspectives on this topic that explore the influence of religion on accounting practices beyond religious frameworks, stating: “Few studies take a macro-perspective to consider how religion influenced (or potentially could influence) accounting outside of religious institutions” (Cordery, 2015, p. 430). Most of the prior literature in this area has tended to focus on one period.

Closing this gap is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of the moral underpinnings of modern accounting practices, particularly in relation to Western capitalist norms (de Lautour, 2017) that often derive from Anglo-Protestant ethical codes (Weber, 1992). By analysing the historical interplay between moral accountability and accounting, this paper aims to show how the rendering of an account has evolved into a societal expectation, contributing to our understanding of accountability in both historical and contemporary contexts.

To address this issue, the current paper employs a macro-historical lens—an analytical approach that investigates long-term structures and recurring patterns across civilisations (Braudel, 1995; Christian, 2005). By focusing on eschatological themes that span millennia, macro-history enables the identification of enduring motifs of accountability that prefigure and shape accounting practices. Applying this lens of macro-history using mainly secondary sources, the current paper examines the eschatological themes of weighing deeds, the book of deeds, and the role of mediators across various cultural narratives—including that of medieval Ireland. This approach provides insights into how the concept of rendering an account has shaped and been shaped by societal norms over time.

This paper makes several contributions to accounting history. First, it adopts a different focus from prior work, which concentrates on the material process of accounting, namely that of the accounting for one’s own actions in life that takes place at death. Second, it employs a macro-historical theoretical lens, which is not frequently employed in the accounting history area. Third, it reinforces the argument that moral and material accounting are historically intertwined. In revisiting the notion of what it means to render an account the paper aims to show how accounting—beyond its institutional or technical forms—has long been linked with moral judgement and cultural meaning. This perspective positions accounting history not merely as a tool of retrospective description, but as a resource for understanding how accountability has been imagined, represented, and evolved over time.

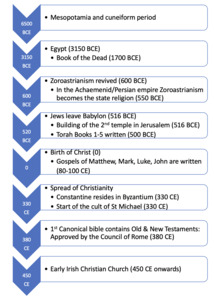

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: first, we present an overview of associated research; then, in the methodology section, we discuss the macro-historical approach; next, we analyse eschatological tropes from the Egyptian, Zoroastrian, Judaic, and Christian traditions.[3] A chronology of the periods relating to the traditions discussed in the paper is given in Figure 1. Finally, the conclusion summarises the main arguments, addresses methodological issues, and suggests future research directions in accounting and eschatology.

Associated Research

Accounting Origins and Eschatological Metaphors

This section considers research into the early history of accounting, from without and within the accounting academic community, and associated research into the link between accounting and religion. Arguments have been advanced in the literature about whether the role of counting and measurement in trade or commerce developed at the same time as eschatological concerns in religion about the rendering of an account for one’s life at the point of death. For instance, Robens and Mikhail (1984) suggest that this notion of “weighing or balancing” migrated from commerce to religion as counting and measurement developed:

“[W]eighing or balancing in its meaning as judging, estimating, levelling and equalising appears to be a fundamental mode of human thinking. The balance at first was a very important instrument for use in trade and commerce, and the development of money is based on the weight … it is not astonishing that in many cultures the balance has symbolic significance and that the invention of the balance has been given a mythological background.” (Robens & Mikhail, 1984, p. 63).

In contrast, Ezzamel (2009, p. 357) argues that “both accounting and accounting for objects, deeds and conduct had a symbiotic relationship” with religious belief. For instance, “in ancient Egypt, counting [already existed] before the emergence of [religious] myth” such as that associated with judgement upon death. Irrespective of how or when counting and weighing emerged, they became intertwined with both commerce and religious practices, and fundamental to both eschatology and accounting.

The history of accounting (or rather proto-accounting and economic activity) has been of interest to researchers of archaeology, archives, philology and economic history for at least a century. In 1972, Posner identified that financial records were the majority of items found in archives of ancient worlds, which included Pharaonic, Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Persia (Posner, 1972). In fact, the study of ancient record-keeping, archives and the development of writing all strongly link the beginnings of accounting to the development of more complex human activities during the time between 6000 and 5000 BCE (Schmandt-Besserat, 2014). This period is associated with state development in the near Middle East, especially involving those civilisations concerned with regulating irrigation and water access. Archives of different writings (on baked clay, papyrus, stone, etc.) have been uncovered that detail the stockpiling of food and materials, the maintenance of armies, religious observances, the production of the latest technologies linked with metalworking, and the building of large monuments.

Counting, as demonstrated by the token method in Neolithic times (c. 7500–3500 BCE), prior to the emergence of these more complicated state developments, has been shown as a basis for all subsequent writing systems. For example, Schmandt-Besserat (1996) analyses the use of tokens to keep track of animals, humans and goods, for domestic consumption, and trade, using archaeological collections across many locations, cultures and times. Further, she demonstrates that the rudimentary symbols used to differentiate between, say, lambs and sheep, influenced the rise of writing in Mesopotamia, among other early civilisations (Schmandt-Besserat, 1996).

Steinkeller (2003, p. 44) presents, in some detail, several management accounting examples from Babylonia in the third millennium BCE where stocks of copper and the production of goods for farmers were managed via the documenting of amounts, or the recording of labour “extracted from the un-skilled workers of the UN-il or éren classes”. Inscribed clay tablets found at Umma (a Sumerian site in Iraq) functioned “as a closely interconnected system, consisting of a chain of receipt tablets, linked to one another by balanced accounts” (Steinkeller, 2003, p. 42). Romer notes the similarities in accounting forms, using grid systems and tokens, found in Mesopotamia, and early Egyptian tomb-offering accounts of 3500 BCE (Romer, 2012). Building on this theme, Molina (2016) provides an interesting overview of the dispersal and fragmentation of a large archive of accounting and bookkeeping records from Mesopotamia circa 2110–2003 BCE. An analysis of clay tablets and tokens from the archives of the Achaemenid Empire, which at that period governed both Persia and Mesopotamia (509-494 BCE), demonstrates the further development of accounting techniques that allowed the government of the time to control the allocation of scarce resources (Namazi & Taak, 2022).

There is evidence for standard weights appearing circa 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, with fundamental values called shekel (translated as something hung or suspended) or mina (a count). These weights were used both for production, such as measuring ratios of tin and copper to produce bronze, and for exchange, by comparing the equivalence of goods, or bullion (Hafford, 2005). According to Ialongo et al. (2021), further standardisation of weights occurred throughout Western Eurasia during the next 2,000 years, which showed an economic interdependency of raw materials during the Bronze Age, from Europe to the Indus.

A number of authors note the persistence across cultures and religions of weighing or balance metaphors adopted from the contemporary technologies of commerce and account-keeping discussed above. For example, Brandon (1967) provides an early comparative study of the history of judgement at the point of death in major religions; in a later paper, they compare the weighing-of-the-soul motif in the Egyptian and Christian eras (Brandon, 1969). Seidenberg and Casey (1980) build on this work and investigate the ritual origin of the balance in a range of cultures and religions, as well as the history of weights and balances. More recent studies such as Robens, Jayaweera and Keifer (2014) provide a comprehensive overview of the history of weights and balances across cultures. Their chapter on the balance as a symbol and object of art is particularly relevant to the discussion in this paper. Finally, Graham (2023) traces aspects of the weighing of souls or fate, found in ancient Greece, through time.

Irish Accounting History

Despite Ireland’s rich cultural and religious heritage, Irish accounting history in the early Christian era remains relatively underexplored. As Clarke (1996) notes, studies of Irish accounting history have largely focused on commercial and professional developments from the 17th century onward, with minimal investigation of earlier religious or monastic contexts. This may be partly due to the lack of surviving systematic ledgers from early Irish monasteries—a gap suggested in the historiography by Ó hÓgartaigh (2008). Nevertheless, evidence from early medieval Irish religious manuscripts, such as annalistic entries and marginal notations, indicates that monastic communities recorded land donations, tributes, and bequests as part of their spiritual and administrative functions (Valante, 2006). The interplay between spiritual accountability and material record-keeping is evident in medieval monastic records (Dobie, 2024)—including those in Ireland. For instance, the notes on religious texts such as the Book of Kells produced by early medieval Irish monastic communities recorded several different types of economic transactions (Valante, 2006). In this way, monasteries maintained records reflecting a concern for (i) the management of their “earthly” resources, and (ii) the “avoidance of sin” associated with property ownership given their vow of poverty (Dobie, 2024). These proto-records, though not accounting books in the formal sense, illustrate the embedding of economic stewardship within eschatologically motivated frameworks; that is, Irish monastic institutions sought to balance material management with moral accountability, a theme consistent with wider patterns across the ancient world.

Accounting and Religion

Beyond the Irish example, a growing literature explores the links between religion and accounting as both a practical and ethical tool. Joannidès and Berland (2010) note that there are different strands of research concerning the interplay of religious belief and actual accounting practice. Often, the research is self-selected because the author’s religious belief provides a particular ethical motivation and, in many instances, case studies are employed because the author is a participant-observer in the religious structures of interest. Joannidès and Berland’s (2010) overview considers mainly Christian accounting practices, but Muslim, Jewish, and Hindu belief systems also have accounting research agendas. Thus, researchers in accounting and religion include those who would like a specific religious ethos to inform accounting practice (e.g., Jacobs & Walker, 2004). or are trying to resolve the tensions inherent in, say, those religions that proscribe usury, and Western accounting as well as banking practices (Riaz et al., 2023).

Cordery (2015) reviews the literature on accounting history and religion over a 30-year period, noting that most research focuses on case studies of accounting by a religious group, rather than investigating how religions may have influenced accounting practice (Cordery, 2015). In their review chapter, which discusses religion and accounting history, Carmona and Ezzamel further conclude that: “Research on accounting in sacred and religious texts is sparse and fragmented. There is considerable potential to explore such texts in relation to a variety of accounting themes (such as accountability, governance and wealth).” (Carmona & Ezzamel, 2020, p. 623).

This current paper responds to the call for further research in Carmona and Ezzamel (2020); it explores the history of accounting practice further by adopting a different focus from prior work which concentrates on the material process of accounting, namely that of the accounting for one’s own actions in life which takes place at death. This focus is therefore one that deals with the moral values of early cultures and draws on evidence in the important historical texts and images of several traditions, namely Egyptian, Zoroastrian, Judaic, and Christian, ending with the emergence of double-entry bookkeeping in Western history in the late 16th century.

Methodology

Macro-history functions in this paper as both a methodological approach and a theoretical lens. As a theory of historical change, macro-history seeks to identify deep structural continuities, longue durée transformations, and the cultural transmission of core motifs across time and space (Christian, 2005). It enables the study of how key moral narratives, such as judgement, balance, and accountability, become embedded in social systems, including accounting. The use of macro-history as a research method is prevalent in different fields such as sociology (Mjøset, 2015), geography (Wescoat, 2023), history (Gibbons, 2003), and especially economic history (Braudel & Matthews, 1982) which has a particular affinity with accounting history.

Macro-history adopts a “reductionist analysis, with a top-down method … produc[ing] generalised understandings of historical change” (Carnegie & McBride, 2023, p. 252). As Inayatullah (1998, p. 381) argues, macro-history not only operates as a method but as a theoretical lens: “Macrohistory is thus both nomothetic and diachronic” in its search of “patterns [and] even laws of social change”. It searches for large-scale trends over a long period of time to understand the origins of change and the development of society. This approach often involves primary materials and sometimes includes tables and graphs of economic information to identify stages of human development. However, while primary materials are invaluable for detailed studies of specific events or periods, historians working on transnational, longue durée or global themes often engage critically with secondary sources. Several historians have highlighted that the vast scope of macro-historical inquiry—spanning centuries (Tosh, 2022), continents (Christian, 2011), or civilisations (Braudel, 1995)—renders reliance on primary sources alone impractical. Academics have suggested that secondary works provide the necessary scaffolding to contextualise and integrate patterns across time and space. Indeed, Tosh (2022) underscores the importance of secondary sources in shaping research questions and providing context, which is particularly vital in macro-historical research that spans extensive temporal and spatial dimensions. For this reason, the current investigation uses the macro-historical approach while focusing mainly on secondary sources.

In implementing this macro-historical approach, the research was structured around three tropes found in the earliest images and texts associated with the Final Judgement and their strong underlying basis of accounting for one’s actions in life: weighing, books of deeds, and mediators, These tropes were chosen because they present early, sustained, and iconographically rich expressions of judgement/accountability that persisted into Western religious traditions. First, the different religions of Egyptian, Zoroastrian, Jewish and Christian traditions were identified and their historic links investigated. Second, religious texts and images associated with the Final Judgement from each period and religion were reviewed. A cross-cultural comparison was then made to trace the continuity, migration, or reinterpretation of symbols and their relationship with the main concepts, thereby testing our ideas concerning the persistence of these three themes and their relationship with contemporaneous accounting practice.

Within accounting, the use of macro-history is relatively uncommon. Indeed, one of the few papers to adopt this approach in the accounting area is Alawattage and Wickramasinghe (2009, p. 379) who examine the emancipatory potential of accounting “to suppress or hegemonise … indigenous resistance implicated in emancipatory potential [of] … a distinct subaltern group in Ceylon Tea”. Carmona and Ezzamel also note the imbalance between micro and macro focuses in reviewing religion and accounting history research:

“Perhaps unsurprisingly, this review has revealed that some topics have been extensively researched—in particular, the micro focus, while others have been sparsely explored in particular, the macro perspective on the interrelationship between accounting and religion and how accounting is presented in religious texts.” (Carmona & Ezzamel, 2020, p. 623)

As the name suggests, macro-history is associated with the study of an issue over relatively long periods of time, often covering hundreds and thousands of years. It examines an issue at the broad macro level “to identify historical patterns of what is happening … that takes into account … long-term historical trends” (Sadovnichy et al., 2023, pp. 17–18). A recent paper that explores the historical roots of environmental and ecological accounting “from the dawn of time” takes a similarly broad view (Atkins et al., 2023). According to Sadovnichy et al. (2023, pp. 17–18), a macro-historical approach helps to avoid “historical myopia” and reduce subjectivity when studying contemporary issues. The current paper employs a macro-historical theoretical perspective, treating historical eschatological themes not simply as a sequence of events but as enduring symbolic systems that shape activities like accounting.

There are a number of terms for research that considers longer timescales than those of event-driven historical narratives or micro-histories, including ‘Great’, ‘Macro’, ‘World’ and ‘Global’ (Christian, 2005; Crossley, 2018). These terms are also associated with the concept of ‘Big History’, first used by Christian in 1991, which describes those histories that use a timescale which starts much further back in geological time to consider historical change (Christian, 1991). In addition, there is the legacy of Fernand Braudel, who is regarded as one of the most important social and economic historians of the 20th century (Forster, 2018). In the preface to a collection of his essays published in 1969, Braudel stated as follows:

“The way to study history is to view it as a long duration, as what I have called the longue durée. It is not the only way, but it is one which by itself can pose all the great problems of social structures, past and present. It is the only language binding history to the present, creating one indivisible whole.” (Braudel & Matthews, 1982, p. viii).

Peter Burke states in his overview of the French Annales School, which was led by Braudel from 1956 until he retired in 1976:

“Even more significant for historians is Braudel’s original treatment of time, his attempt to divide historical time into geographical time, social time and individual time and to stress the importance of what has become known (since the publication of his famous article on the subject) as la longue durée.” (Burke, 2015, p. 47)

The positioning of macro-history as a theory of time and transformation is echoed in Christian’s (2005, p. 27) view that “seeing the past through many different time frames ought to offer a richer, fuller and [a] more coherent understanding of the past in general”. He emphasises macro-history’s theoretical value in framing insights across different temporal scales, what Jacques Revel earlier termed “the play of scales”. Christian (2005, p. 28) notes that such an approach “appears not as the opposite of microhistory, but as its complement”[4] arguing that “Macrohistory and microhistory are really just different ways around the circle.” While recognising that a detailed investigation of a very short period of time can offer useful insights, Christan (2005, p. 28) further states that “the opposite is also true; by trying to grasp very large themes, you can sometimes find to your surprise that you are closing in on the intimate and the personal”.

In the following analysis, we are further informed by a secular tradition of studying religious texts, rather than any theological concerns associated with an interpretation of the divine or religious exegesis, and on trying to understand the philological, philosophical and socio-historical contexts of such documentary evidence. We therefore take an interpretive stance on textual analysis as suggested by Willis (2007).

Macro-historical Analysis

This section analyses different cultures from Egyptian to Christian times using the macro-historical approach noted above, by studying important religious texts and images of each tradition and culture in turn, looking at similar themes and noting changes and differences which reflect the changing societal beliefs over time. We start in Egypt, where the Book of the Dead was an important religious illustrated text from approximately 1700 BCE until 100 BCE. Next, concepts of judgement at the point of death are found in Zoroastrian (circa 600 BCE) and the later Manichean texts, which were established in what was then Persia and is now Iran. Then we consider Judaic and Christian texts and the images associated with the cult of St Michael (which began with Emperor Constantine’s building of a church of St Michael in the 4th century CE). We note that the Old Testament of the Christian Bible is based on books of the Torah, of which the first five books were written around 500 BCE, when Jewish communities were returning from exile in Babylon (now Iraq) (see Figure 1 for a more detailed chronology). In each of these periods we identify the three eschatological themes discussed above: (i) weighing; (ii) the book of deeds in which good and bad deeds are recorded; and (iii) the role of mediators or intercessors. The following sections look more closely at the important texts and images of these religions, how, over time. the motif of being ‘weighed in the balance’ became a calling to account for one’s life at the point of death, and how this motif was further assimilated into normal social beliefs and customs outside of religious belief.

Egypt

Ezzamel (either on his own, or with Hoskin or Carmona) contributes many interesting examples of early accounting practices in ancient Egypt, which link the palace, the temple, tax collection,[5] and individual family units with what may be considered proto-accounting practices (Carmona & Ezzamel, 2006; Ezzamel, 2009, 2012; Ezzamel & Hoskin, 2002). Ezzamel also details much of the religious context for the scribal accounting process; for example, scribes, who were often priests, kept accounts for all state activities, such as temple offerings, collecting taxes, palace accounts, and oversight of building activities; they also produced funerary texts (Ezzamel, 2012). Here we focus on the illustrated guidebook for reaching the afterlife, the Book of the Dead, which emerged from earlier written guides circa 1700 BCE, and which was in use until approximately 100 BCE (Taylor, 2010a) (see Figure 2, which is commonly reproduced in the literature as an example of Egyptian rituals at the end of an individual’s life.)

The Book of the Dead details the required rituals and spells that allowed access to the Western land of abundance, a place of eternal life after death. It includes spells to placate over 40 different deities and demons, and always details the steps required to pass the important judgement of Osiris, at which one’s heart, which was regarded as the most important human organ, was weighed in the balance by Anubis against the feather of Maat, the symbol of correct and morally acceptable behaviour (Taylor, 2010b). If the dead person’s heart was found to be “heavy with sin”, and therefore heavier than Maat’s feather, then Ammit (a monstrous demon) would eat it; without a heart, the dead person’s chance of an afterlife would disappear (see also Ezzamel, 2012).

What is interesting about this motif is that it led to the discovery that over a period of time (approximately 1,500 years) scribes in ancient Egypt systematised the production of this important and expensive instruction manual. Originally, only pharaohs were buried with a Book of the Dead, and other important funerary items, including coffin texts, which included similar incantations. Subsequently, as a more elaborate funeral process was extended to family members of courtiers and dignitaries, these papyri were included as part of the preparations for burial across a larger group. Such a scroll would be created with empty picture spaces in which the buyer’s image and name would be inserted at the critical points in the journey to the afterlife, so that they could confront, in person, the various gods and monsters, and speak the required words to pass through each stage (see also Verhoeven-van Elsberger, 2023). Thus, a wealthy enough person could maximise the possibility of attaining the Egyptian afterlife, ensuring that the correct rituals were enacted, both at their deathbed, and after death. Those with less status were also aware of this particular eschatology: there is evidence that scribes had their own Book of the Dead, and those who created the funeral monuments had prayers and amulets inscribed for their own funerals, which included those from the Book of the Dead canon (James, 2007).

This systemisation of ritual, under the aegis of the scribe, is interesting, but so is the description, (i) of the scribe as accountant, (ii) of the deity Thoth, ibis-headed god of magic, scribes, science, bringer of writing, note-taker of the life account and judge of the dead and, (iii) the motif of the self being weighed in the balance. Since 2011, various projects have identified and digitised access to approximately 3,000 items relating to the Book of the Dead. This work includes materials relating to funerary practices during the Greek and Roman periods (800 BCE–600 CE) and shows the persistence of the tropes detailed above in later Egyptian periods, which overlap with the early Christian era discussed below (EADH 2018; Lucarelli & Stadler, 2023).

Zoroastrianism and Manichaeism Religions

Zoroastrianism emerged around 1400 BCE, in a pre-literate culture and is based on the teachings of Zoroaster (or Zarathustra), a figure whose life and existence cannot be historically verified. The basic tenets of the religion are found in the Gathas, 17 short hymns, which are part of an Iranian and Indian traditional culture (Clark, 1998). The particular importance of this belief system is that it presents an ethical dualism between good and evil: between these two, a follower must consciously choose. Of interest to this paper is the text that describes the explicit judgement carried out when a person dies, and the emphasis in the religion on an account of good and bad deeds. The soul arrives at the “bridge of the separator”, or account-keeper’s bridge, where it is assessed by three angels named, Mithra, Sraosha and Rashnu, before whom “the life-account is rendered and the good and bad deeds respectively are weighed in the balance” (Clark, 1998; A. V. W. Jackson, 1928).

“As a second important point in the general ethics of the religion, we must notice the doctrine of man’s responsibility to account. A strict watch over each man’s actions was believed to be kept by the divinities. All good deeds were carefully recorded; all sinful acts were sternly set down. No doctrine of a recording angel could be clearer and more precise than this of the Zoroastrian creed. These actions were written in an Account-Book and were heaped up to be weighed in the balance at the time of the Individual Judgement. Allusions to such a record and weighing are found throughout the sacred books of Zoroastrianism from the earliest to the latest times.” (A. V. W. Jackson, 1896, p. 57)

This weighing of the soul is regarded by Jackson as being an integral part of Zoroastrian ethics from its inception (A. V. W. Jackson, 1896), being based on an older myth with some modifications, according to Clark (1998). The followers of Zoroaster were presumed to be of two main types: the “elect” are the higher religious members who withdraw from daily life to follow a life of devotion and chastity; the “auditors” or “hearers” are yet to become elect but provide the daily food and wherewithal for the elect to live. These auditors can marry (similar to the idea of the laity in Christian belief systems). Those who were not followers of Zoroaster were treated differently when they died. At the point of death there was a judgement and a division based on the path taken in life—the elect went straight to heaven in the company of a lovely woman, possibly an angel (there appears to be no lovely men for female elects). The auditors did not cross the bridge but waited until they become elect, perhaps through reincarnation, so that they could choose to be more religious in their new life and could then pass directly to heaven. Everyone else, unfortunately, went to hell, accompanied by demons (Boyce, 2001).

The religion that was most directly influenced by Zoroastrianism is Manichaeism, after the teachings of the historical figure, Mani (216–274 CE). Jackson shows how several Zoroastrian beliefs, including the accounting for life/judgement on death, were adopted by Manichaeism. Indeed, both the judgement and the keeping of a life-account were documented in earlier teachings of this religion according to fragments of manuscript found in Turkey and Iran (A. V. W. Jackson, 1923, 1930). These ideas then formed part of the later religious legacies of Manichaeism: those of the Parsees in India and several sects in China (Lane Fox, 1986).

Manichaeism originated in Sassanid Persia in the 3rd century CE and spread across the Roman world until the 7th century. It spread as far as China until the later part of the 14th century. The Cologne Mani-Codex found in Upper Egypt in 1969 provides historical evidence for Mani and his origins in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, Babylonia, as a member of a Jewish–Christian sect, the Elchasaites (Gardner, 2020). Mani is thought to have lived around 250 CE, and his teachings synthesised Zoroastrian, Buddhist and Christian sources. Manichaeism is a Gnostic religion—one of the religions formed in the early Christian era which took some kind of esoteric knowledge as a basis for salvation from the material world. These religions include early Christian sects, Hellenistic Jews, followers of Zoroastrianism, and Greco-Roman mystery religions such as the Mithraic cult, which was popular with the officer classes of Roman armies in the first centuries of the modern era (Fear, 2022; Lane Fox, 1986; Shean, 2010). One of the main legacies of Mani’s teaching in the modern age is that of ‘Manichean Dualism’, or the polarising and conflicting aspects of good versus evil, often depicted as light versus dark. As Gardner notes, this idea is somewhat removed from the early teachings of Mani’s followers but uncovered in later writings (Gardner, 2020).

Jewish and Christian Traditions Including the Irish Christian Context

“In the seventh century, Saint John Climacus reported visiting a monastery near Gaza where every brother carried a small wax tablet on his belt. If he found himself committing (or considering) a sin, he would note it on the tablet, and at the end of the day confess it to the abbot, and the tablet would be wiped clean literally and metaphorically.” (Allen, 2023, p. 260)

As we have seen above, weights were a form of currency and part of proto-accounting in the ancient world, but they also had symbolic meanings (Seidenberg & Casey, 1980). For example, the Old Testament often uses balances and weights to discuss good and evil, as shown in the following text: “If I have walked with vanity, Or if my foot hath hasted to deceit; Let me be weighed in an even balance, That God may know mine integrity” (Job 31.5–6, KJV). A more famous example is found in the Book of Daniel (Daniel 5:27, KJV)[6] when mysterious prophetic words appear on a wall during Belshazzar’s feast:

“And this is the writing that was written, MENE, MENE, TEKEL, UPHARSIN. This is the interpretation of the thing: MENE; God hath numbered thy kingdom, and finished it. TEKEL; Thou art weighed in the balances, and art found wanting. PERES; Thy kingdom is divided, and given to the Medes and Persians.”

The motif of a heavenly book, or book of life, which records the name of the righteous and/or a person’s deeds, is found in Judaic and early Christian writings, namely the Book of Daniel, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and other Second Temple Literature, for the period 200 BCE – 200 CE (Baynes, 2012). This book of life, also associated with the day of judgement for all peoples, is found in the Bible in the Books of Daniel, Isaiah and Revelation. For example:

“And I saw a great white throne, and him that sat on it, from whose face the earth and the heaven fled away; and there was found no place for them. And I saw the dead, small and great, stand before God; and the books were opened: and another book was opened, which is the book of life: and the dead were judged out of those things which were written in the books, according to their works.” (Rev 20:11–12, KJV)

Aho notes that in Revelations there are two books in which someone’s debits and credits (sins and good deeds) are entered: one is a book of accounts, kept on earth, and the other, the book of life, which is a register for those who will enter heaven (Aho, 2005). Various ways of keeping such books are alluded to in Christianity and include the idea of a recording angel. For example, when writing about literacy and power in early Christianity, Lane Fox observes that “Recording angels were a constant, literate police force, active above early Christian saints and sinners”. He further states that “Bede, Eccles. Hist. 5.13 has a vivid story of the imagery of the two heavenly books, good and bad, being balanced against each other during a Christian’s dying hours. Before a New Testament existed, Christians were already a ‘people of the Book’ in this neglected sense: the book of their Recording Angel” (Lane Fox, 1994, p. 133).

Providing a link between Manichean beliefs and that of the early Christian church, St Augustine of Hippo (354–430 CE) spent nine years as a follower of Mani, attaining the status of an auditor: one who looks after “the elect” but hopes to join them when reincarnated, as noted above. After he turned back to the Christian faith, St Augustine’s subsequent writings were very influential, in that his resolution of an eschatological dispute concerning both personal and general judgements, which emphasised that the fate of the soul was determined at death, was adopted as part of the mainstream Christian faith for the period up to and including the European Reformation (Lane Fox, 2016).[7]

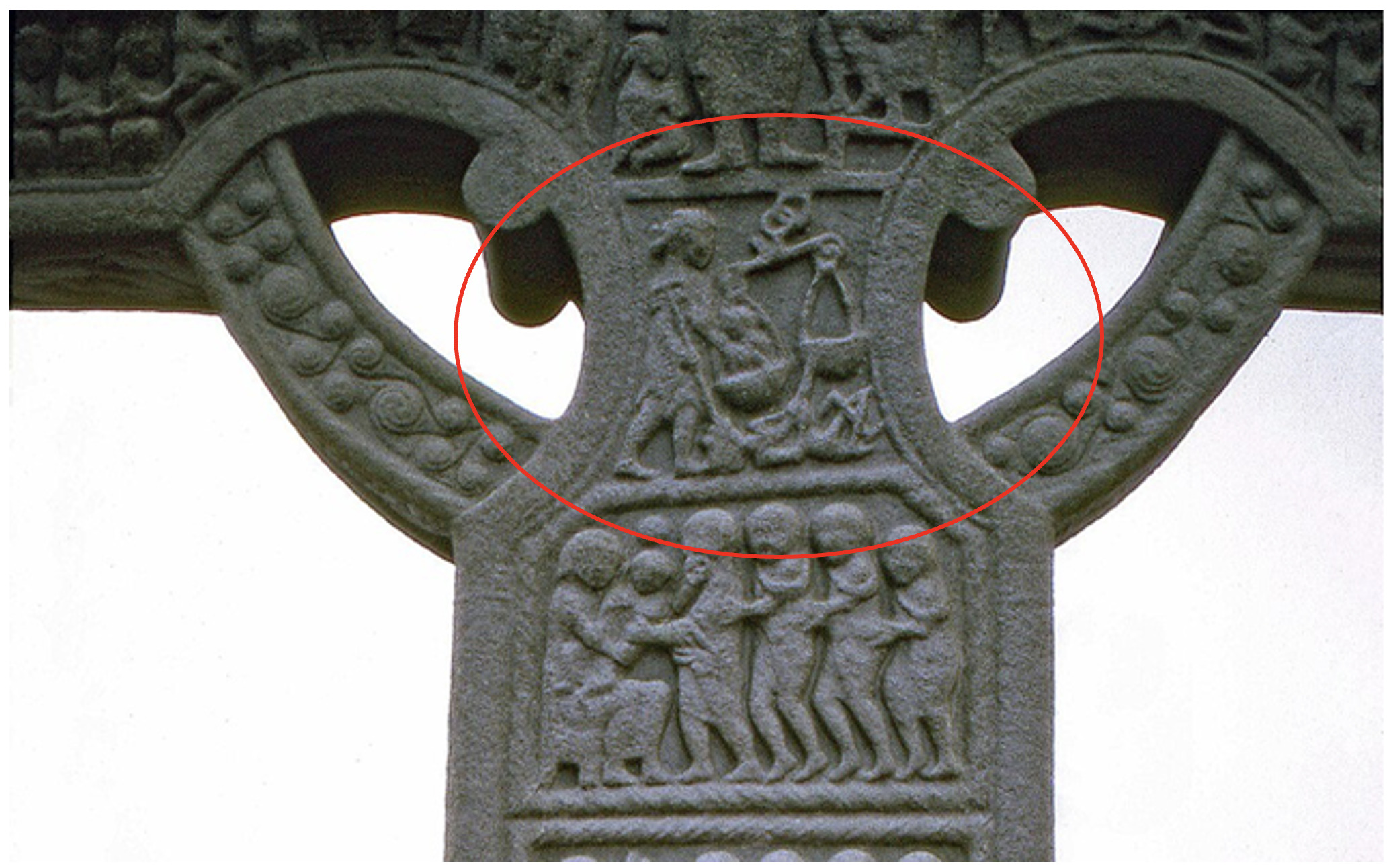

Images of St Michael weighing souls are found throughout the medieval period, some carved in stone (Veelenturf, 2017) and others in later medieval paintings (Robens et al., 2014). One of the earliest known examples of this image during the Christian era, with the Archangel Michael performing the weighing task, is in Ireland (Harbison, 1992). On Irish high crosses, St Michael is depicted weighing souls, often in a contest with a tiny devil beneath the scales. For example, on Muiredach’s High Cross (see Figure 3) this imagery is clearly represented.

“[A] particular judgement is carved showing the Archangel Michael weighing the soul … within a balance, but doing so in contest with a tiny devil, who is pulling at the other scale underneath. St Michael pins the devil down with his own staff.” (Veelenturf, 2017, p. 222)

Parallels have been drawn between this motif and the eschatological imagery in the Egyptian Book of the Dead, which also features the weighing of deeds. Despite the chronological and geographical distance between Egypt and Ireland, Veelenturf (2017, p. 225) argues that it is unlikely such similarities are merely coincidental. As he notes, “the shared combination of eschatological features on the Cross of Muiredach” and in the Book of the Dead makes an independent origin improbable. As Quinn (2005, p. 205) argues, “The structure and ethos of the Early Irish Church is so suffused with … North African characteristics that to attribute it to second-hand influences begs too many questions.” Such a view supports the possibility that the Irish Church absorbed eschatological and moral-accounting motifs not solely from continental European traditions, but through broader trans-Mediterranean exchanges reinforcing the macro-historical proposition of shared symbolic motifs across civilisations.

Further evidence from the 13th century onwards in early Irish poetry has highlighted the role of St Michael imagery “with his scales in which the deeds of individuals were to be weighed” (Ryan, 2009, p. 188). As part of the Celtic tradition, St Michael was expected to intercede in order to secure a favourable result for the deceased during this weighing of souls[8]:

“Michael, ever-blooming tree, true master of the eternal home, is my battle-shield against the world; may he counter-weigh my debts (in the scales).” (McKenna, 1931, Poem 11, Stanza 32).

Lane (1989) also notes that images of the Last Judgement appear on many medieval churches, often carved on the tympanum (the pediment above the doors), and that this image occurs in several Books of Hours, illustrated devotional texts used for personal contemplation. A typical example of St Michael as the weigher of souls is found in Roger van der Weyden’s large panel of the Last Judgement (see Figure 4). Commissioned by a wealthy patron for the Hôtel-Dieu in Beaune in Burgundy between 1443 and 1451, the painting places St Michael holding the scales directly below Christ. This image is frequently cited in the literature as a canonical depiction of eschatological judgement. Aho describes the emergence of double-entry bookkeeping in the early medieval period and shows that this was closely related to an individual’s religious belief and behaviour, making strong links between confession and bookkeeping and for the religious and moral roots of modern accounting (Aho, 2005). He argues that religious observances, such as confession, constituted a form of control and self-discipline in the pre- and post-Reformation Catholic Church.[9] Thus, a priest, as confessor and arbiter of sin, was a mediator in the process of accounting for the self, and ultimately accounting for death. The current paper is less direct about the link between accounting and religion. Instead, it suggests that the trope of weighing and the balance has persisted across many religions and may have led to an acceptance of the need to render an account (balancing debits and credits) more widely, not only in the context of eschatological judgement at death, but also in the conduct of everyday economic life, including the management of property, trade or debt.

Discussion

This paper demonstrates that the notion of being called to account for one’s life at death has been a powerful and enduring motif across many major religious traditions and associated cultural practices. Through the macro-historical exploration of eschatological themes, namely (i) the weighing of deeds, (ii) the keeping of a ‘Book of Life’, and (iii) the role of mediators or intercessors, this study sheds light on how these religious and moral concepts have influenced the development of accounting systems and practices. The findings reveal not only the continuity of these motifs but also their capacity to adapt to and shape societal norms over time.

In his 2009 paper, “Books to be practiced”, Quattrone identifies four concepts underpinning the emergence of accounting. The one most relevant to the current research is his emphasis on the importance of visual images in transmitting and stabilising accounting ideas. Visualisation, he argues, is integral to accounting practice because images communicate concepts of order, memory, and accountability in ways that transcend literacy barriers. In our context, the images of judgement at death, particularly the weighing of souls and the Book of the Dead, performed a similar role. They acted as powerful “visual treatises”, embedding in the popular imagination the notion that life itself must be accounted for, weighed, and recorded by experts. In pre-literate societies, these images functioned as teaching tools, shaping habits of thought that equated moral worth with the balancing of accounts. This is why judgement-at-death matters for accounting history: it created a cultural template in which accounting metaphors were already familiar, intelligible, and authoritative. The resonance between Quattrone’s (2009) analysis of visualisation and the religious imagery examined here reinforces the argument that the emergence of accounting relied not only on technical procedures but also on deeply rooted symbolic systems that made the very idea of “rendering an account” both natural and compelling.

The symbolic and practical importance of weighing as a means of judgement is perhaps one of the most universal aspects of the eschatological tradition explored in this paper. From the physical balances in Egyptian rituals—where the heart was weighed against the feather of Maat—to the Christian imagery of St Michael weighing souls (as evidenced in medieval art and Irish high crosses), the concept of ‘balance’ conveys a dual sense of moral and material accountability. This emphasis on measurement and fairness may not be coincidental but reflects a human need to reconcile abstract ethical principles with concrete actions.

Similarly, the motif of recording in the book of deeds highlights the universality of record-keeping as a way of preserving moral and ethical evaluations. Whether it was the Egyptian scribe maintaining funerary texts, the Zoroastrian angels keeping accounts of good and bad deeds, or the Christian imagery of heavenly books opened on Judgement Day, the act of recording illustrates the shared human understanding that actions must be documented for them to be evaluated justly. This parallels the central role of documentation in modern accounting, where maintaining accurate records is critical to ensuring fairness, accountability, and transparency.

The concept of mediators or intercessors, as seen in the priestly scribes of Egypt, the angels of Zoroastrianism, and Christian priests in the medieval confession system, demonstrates how accountability has often been facilitated by an intermediary figure. These mediators were responsible for interpreting and enforcing moral and ethical codes, much like accountants today act as interpreters and enforcers of financial standards. This alignment underscores the dual ethical and administrative role of accounting professionals, whose work, like that of their historical counterparts, bridges the gap between individual actions and institutional accountability.

The Irish evidence demonstrates an early regional adaptation of eschatological accountability in Western Christianity. Some of the earliest examples of the concept of ‘weighed in the balance’ are found in Irish high crosses, poetry and literature. Monasteries functioned as mediators of both spiritual and economic accounts, with abbots acting as intercessors who balanced divine judgement and terrestrial governance. The emphasis of Celtic monasticism on personal austerity and the transmission of the Christian “message [about judgement at death] externally, via language, artefacts, myth and ceremony, to the believers” (McGrath, 2007, p. 219) mirrors the dual role of scribes in ancient Egypt or confessors in medieval Europe, reinforcing this paper’s argument that moral and material accounting are historically intertwined.

The continuity of these motifs into modern times reflects the profound moral roots of accounting practices. From the early 20th century, Max Weber’s analysis of Protestant ethics and their influence on capitalism illustrates how the religious focus on self-discipline, accountability, and moral evaluation has informed the development of Western economic systems (Weber, 1992). More recent studies, such as Aho’s (2005) examination of confession as a precursor to double-entry bookkeeping, highlight how religious traditions provided both the ethical framework and technical innovations that shaped modern accounting.

Understanding this historical lineage is crucial in contemporary discussions about the ethical dimensions of accounting. Practices such as environmental, social, and governance (ESG) reporting, for example, echo the ancient principles of moral accountability, extending the concept to encompass responsibility toward society and the planet. As Atkins et al. (2023) argue, the integration of environmental concerns into accounting practices reflects a broader recognition of the moral imperatives embedded in the discipline.

Adopting a macro-historical approach has allowed this study to uncover long-term patterns and draw connections between seemingly disparate traditions and practices. As a theoretical lens, macro-history provides a framework for interpreting the persistence of symbolic motifs—such as balance and recording-keeping—as institutionalised practices in modern accounting. Seen in this light, images of judgement at death matter because they naturalised the very act of rendering an account. By presenting salvation and moral worth in terms of weighing, balancing, and recording, they helped make accounting a familiar and persuasive way of organising life, long before it became a technical discipline.

Conclusion

The historical exploration of accountability at the intersection of eschatology and accounting reveals a number of implications for the ethical foundations of the accountancy profession today. The persistence of eschatological motifs in accounting practices reminds us that the discipline is not merely a technical field but one deeply rooted in ethical considerations. Concepts such as fairness, transparency, and integrity, which are central to modern accounting standards, resonate with ancient traditions of moral evaluation. This recognition should inspire practitioners and scholars to engage more deeply with the ethical dimensions of their work. In an era marked by financial scandals, corporate misconduct, and environmental crises, the historical roots of accounting provide a powerful reminder of its moral purpose. Accountability should not only serve as a means of enforcing compliance but also as a tool for promoting justice and equity in society.

However, the use of macro-historical analysis poses challenges. The reliance on secondary sources, translations, and interpretations may introduce biases or oversimplifications, while the Western focus limits the applicability of findings to non-Western contexts. Addressing these limitations requires further research into non-Western eschatological traditions, such as Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and indigenous belief systems, which also feature rich traditions of moral accountability and record-keeping.

Furthermore, while the macro-historical perspective offers valuable insights into long-term trends, it cannot fully capture the complexities of specific traditions or cultures. A complementary micro-historical approach, as Christian (2005) suggests, could add to the current analysis by providing additional context and nuance, enriching our understanding of how accounting practices evolved within particular historical and cultural settings.

This study opens several promising avenues for future research. Interdisciplinary studies that combine insights from theology, archaeology, and accounting history could provide a richer understanding of how accounting practices have been shaped by religious and moral traditions. Comparative studies of eschatological motifs in non-Western cultures could broaden the scope of this research, offering a more inclusive perspective on accounting history.

Finally, exploring the implications of these historical motifs for contemporary challenges, such as the rise of ESG reporting, corporate social responsibility, and ethical auditing, could identify new pathways for integrating moral accountability into modern practices. As Dillard and Vinnari (2019, p. 16) suggest, moving from “accounting-based accountability” to “accountability-based accounting” represents a critical shift toward embedding ethical considerations at the core of the discipline.

In conclusion, this study highlights the enduring influence of eschatological motifs on the moral and technical dimensions of accounting. By tracing the evolution of themes such as weighing deeds, keeping records, and the role of mediators across cultures and epochs, using a macro-historical perspective, we gain a deeper understanding of how accounting practices have been shaped by human concerns about morality and justice. This exploration not only enriches our appreciation of accounting’s historical roots but also underscores its continuing relevance as a tool for promoting fairness, integrity, and accountability in contemporary society.

This paper uses the abbreviations BCE (Before Common Era) and CE (Common Era) instead of BC and AD, in line with inclusive and neutral conventions in historical research.

In the current paper, the following terminology associated with sacred “books” is employed. We refer to the Book of the Dead as the funerary text in Ancient Egypt containing spells and instructions to guide the deceased through the afterlife. In our analysis of the Jewish and Christian traditions, the Book of Life recorded the names of the righteous destined for salvation. More generally, we refer to the book of deeds as the “sacred book” under both Egyptian and Judeo-Christian traditions.

Other religions such as Islam are not considered in this analysis. Allah is referred to as Al-Haseeb several times in the Qur’an, meaning ‘the accountant’ or ‘the reckoner’, which signifies counting or calculating. This name highlights Allah’s role in taking careful account of all actions and weighing deeds at the time of death to determine the ultimate fate of each individual. This is beyond the scope of the current paper. Islamic eschatology is rooted in a different historical and cultural context that does not align directly with the current study’s focus. Interested readers on this topic are referred to Dilawati (2022).

There are numerous popular books that use some form of macro-historical lens such as The earth transformed: An untold history (Frankopan, 2023), and The dawn of everything: A new history of humanity (Graeber & Wengrow, 2021).

In ancient societies, taxation practices were deeply intertwined with religious and administrative structures. For instance, temples often served as centres for resource collection, storage, and redistribution, blending administrative and religious functions. In ancient Egypt, as Ezzamel (2012) notes, there was no clear demarcation between sacred and secular activities. Taxation records, therefore, reflected broader systems of accountability that aligned with both the administrative needs of the state and the ideological frameworks of religious institutions. Distinguishing between these overlapping roles provides a better understanding of ancient accounting systems and their purposes.

The Book of Daniel is believed to have been written during the 2nd century BCE, and though there are debates about its provenance and to what degree it is fictional or has some historic merit (see Barton, 2019), these debates do not lessen the importance of this text as a prophetic and apocalyptic narrative which influenced New Testament writing (Barton, 2019; Evans, 2001).

Augustine’s teachings resolved other eschatological problems occupying the early Christian church, including the problem of the date of the end of the world (Lane Fox, 1986).

The motif of ‘weighing in the balance’ has persisted in Irish poetry and literature over the centuries. For example, in his 1918 poem “An Irish Airman Foresees His Death” W. B. Yeats writes: “I balanced all, brought all to mind … In balance with this life, this death.” (Yeats, 1919). Further, in his 1935 autobiography, Yeats reflects on the summation of a life, four years before his death: “When I think of all the books I have read, and of the wise words I have heard spoken, and of the anxiety I have given to parents and grandparents, and of the hopes that I have had, all life weighed in the scales of my own life seems to me a preparation for something that never happens.” (Yeats, 1935, p. 71). While not explicitly religious, the phrase resonates with the broader cultural idea of moral or existential judgement.

Aho’s arguments are supported by further research into the Italian Church and accounting in the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries (Quattrone, 2004).

_by_rogier_v.jpeg)

_by_rogier_v.jpeg)