The authors gratefully acknowledge funding received from Research Ireland’s (formerly The Irish Research Council) New Foundations Programme 2022. We also wish to thank the workshop participants for their valuable insights, which contributed significantly to the development of this research.

1. Introduction

Biodiversity, i.e. the diversity, abundance, and identity of species, their genes, and ecosystems, underpins the ecosystem services that sustain human wellbeing and economic prosperity (Costanza et al., 1997; Marselle et al., 2021). However, nature is in crisis, as human activity is degrading ecosystems faster than they can regenerate (IPBES, 2019). This could have serious consequences for the real economy as over half of global gross domestic product (GDP) depends on nature (World Economic Forum (WEF), 2020). Indeed, biodiversity loss is now recognised as one of the most significant global risks of the coming decade (WEF, 2024), with wide-ranging environmental, economic, and societal consequences (Dasgupta, 2021; IPBES, 2020; World Bank, 2020).

Despite a growing awareness of this crisis, efforts to mobilise finance for biodiversity lag those for climate change (Nedopil, 2023). Although the two crises are deeply interconnected, they are often addressed separately, leading to conflicting priorities and policy trade-offs (IPBES-IPCC, 2021). Significant financial resources are needed to conserve nature and halt, or at least slow, biodiversity loss, estimated to be between US$722 billion and US$967 billion annually (Deutz et al., 2020). However, progress remains slow, and scalable financial solutions are still emerging (Flammer et al., 2025). Finance is increasingly recognised as essential to biodiversity protection (Dasgupta, 2021). The European Union (EU) Biodiversity Strategy for 2030, which commits to unlocking at least €20 billion annually from public and private sources for nature-related investments and the development of financial instruments and incentives to support “nature-positive” outcomes, is now a key policy focus for EU Members States. However, academic research examining biodiversity finance remains limited (Nedopil, 2023), particularly in terms of actionable solutions for mobilising capital and engaging stakeholders. Research is especially scarce on potential ways in which national contexts shape biodiversity finance pathways, and the barriers and enablers encountered at local levels. This study addresses this gap by asking how sustainable finance mechanisms can be designed and mobilised to support biodiversity goals in Ireland, and what the key challenges, enablers, and stakeholder roles are for achieving this.

Ireland provides a timely and relevant context for this investigation as it faces acute biodiversity challenges with over 90% of its protected habitats in poor or declining condition (NPWS, 2019) and where biodiversity loss has been declared a national emergency. In response, the Irish Government has adopted its most ambitious biodiversity agenda to date. The fourth National Biodiversity Action Plan (2023–2030), launched in 2024, is the first to be backed by legislation, includes legally binding targets, and explicitly calls for blended public–private financing mechanisms. A comprehensive financial needs assessment of the investment required to meet the objectives of this plan was conducted by Bullock and McGuinness (2024). Ireland has also committed €3.15 billion through its Climate and Nature Fund and supported the EU Nature Restoration Law (Regulation (EU) 2024/1991), reflecting a strong policy drive to align economic and environmental priorities. Ireland is also investing in its sustainable finance infrastructure. The establishment of the International Sustainable Finance Centre of Excellence (ISFCOE) and a dedicated Climate Change Unit within the Central Bank of Ireland underscore its ambition to become a leader in green and sustainable finance. Despite these developments, there remains a limited understanding of how finance can concretely support biodiversity outcomes in Ireland. This study seeks to help bridge that gap.

We employ a qualitative participatory methodology, drawing on three interdisciplinary workshops held across the island of Ireland in 2023. These brought together stakeholders from academia, government, finance, and the agricultural sector. Appreciative Inquiry (AI) was used in two of the workshops to generate forward-looking, collaborative insights.

Our analysis identified seven interrelated themes shaping the development of biodiversity finance in Ireland. These include a growing awareness of the biodiversity crisis across sectors, increasing recognition of the climate–biodiversity nexus and its trade-offs, and the emergence of business cases for nature-positive action. The evolving role of financial institutions and product innovation was also emphasised, along with strong investor demand for additionality and verified ecological outcomes. Participants highlighted the importance of co-created solutions involving the agricultural and business sectors, and the critical role of community engagement in ensuring legitimacy, trust, and successful local delivery.

This study contributes to the growing field of biodiversity finance by offering context-specific, stakeholder-informed insights into practical pathways for ecological recovery. In doing so, it positions Ireland as a potential policy and financial innovation hub in addressing one of the defining environmental challenges of our time.

The paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 reviews literature on biodiversity finance and participatory governance. Section 3 outlines the participatory methodology, including our rationale for using AI. Section 4 presents the findings, highlighting key themes and co-produced propositions. Section 5 discusses implications for theory and practice. Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Literature Review

Biodiversity underpins ecosystem services essential for human wellbeing and economic stability (Costanza et al., 1997; Marselle et al., 2021), yet the continued degradation of nature places both at risk. The World Economic Forum (WEF) (2020) estimates that over half of global GDP is moderately or highly dependent on nature. Despite this, biodiversity loss has accelerated, with human activity now outpacing ecosystems’ capacity to regenerate (IPBES, 2019). Its consequences are not only environmental but also economic and social, including heightened risks of future pandemics (IPBES, 2020), substantial financial losses (World Bank, 2020), and systemic risk to global markets (Almond et al., 2020; WEF 2023). Biodiversity loss, alongside climate change, is now widely recognised as one of the twin environmental crises of our time (Flammer et al., 2025; Karolyi & Tobin-de la Puente, 2023).

In response, policy frameworks have evolved significantly, from early international agreements such as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) to the more recent Kunming–Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), which sets ambitious targets for 2030 (CBD 2022; Fenichel et al., 2024; Lehmann, 2023). Biodiversity is also central to the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), contributing directly to 10 and indirectly to all 17 (Blicharska et al., 2019; Mace et al., 2018). In the European context, biodiversity is one of six environmental objectives in the EU taxonomy for sustainable activities, underscoring its integration into the sustainable finance agenda.

From an economic perspective, efforts to quantify and incorporate the value of biodiversity began to emerge in the literature as early as the 1990s. Research by Weitzman (1992) and later contributions by Heal (2000), Nehring and Puppe (2002), and Brock and Xepapadeas (2002) laid the groundwork for a more structured economic theory of biodiversity. These efforts culminated in the push to integrate biodiversity into mainstream economic and financial decision-making (Natural Capital Coalition, 2016; TEEB 2008). Since the Eleventh Session of the Conference of the Parties (COP11) in 2012, global biodiversity policy has increasingly emphasised the need for financial system engagement and investment mobilisation (Seidl et al., 2024).

This has led to growing interest in biodiversity finance, i.e. the allocation of financial resources to protect and restore ecosystems (Deutz et al., 2020), with the current shortfall in biodiversity funding labelled as the “biodiversity finance gap” (Karolyi & Tobin-de la Puente, 2023; World Economic Forum (WEF), 2024). The EU Biodiversity Strategy for 2030 has committed to mobilising at least €20 billion annually, but delivering this investment at scale requires the development of new financial instruments and public–private collaboration.

Despite policy momentum, the academic literature on biodiversity finance remains relatively underdeveloped. Much of the existing work focuses on risk, including difficulties in quantifying and pricing biodiversity-related risks due to the complex, non-linear dynamics of ecosystems (Mathilde et al., 2021). Giglio et al. (2023) propose methods for integrating biodiversity risk into equity pricing, with Ma, Wu and Zeng (2024) investigating the impact of such risk on stock returns, Pi, Jiao and Shin (2025) analysing its impact on environmental, social and governance (ESG) performance, while Hudson (2024) highlights the implications of biodiversity risk for banks and insurers. However few studies offer concrete financial solutions or examine the enabling conditions for innovation and capital mobilisation in this area. Research on biodiversity finance continues to lag that of climate finance (Ma et al., 2024; Nedopil, 2023), with a noticeable absence of practical tools or mechanisms designed to operationalise investment (Hutchinson & Lucey, 2024). Some exceptions are emerging. Flammer et al. (2025) present a conceptual framework for attracting private and blended capital to biodiversity projects and document the types of capital attracted by different project features. They underscore the central challenge of additionality, noting that biodiversity conservation delivers public goods that often lack clear revenue streams, leading to under-provision (Heal, 2020) and a “free rider” problem in biodiversity investment markets.

This study contributes to addressing these research gaps by exploring how sustainable finance mechanisms can be designed and mobilised to support biodiversity goals in Ireland, a context that has experienced a notable acceleration in policy ambition but limited academic attention. Ireland’s fourth National Biodiversity Action Plan (2023–2030) is the first to be backed by legislation and supported by dedicated finance, including a €3.15 billion Climate and Nature Fund. The State’s support for the EU Nature Restoration Law, the establishment of the International Sustainable Finance Centre of Excellence (ISFCOE), and recent initiatives by the Central Bank of Ireland and Euronext Dublin all demonstrate growing institutional commitment to aligning finance with biodiversity outcomes.

However, despite these developments, the literature offers little insight into how these structures function in practice, or how finance actors, policymakers, and civil society can collaborate to scale investment and overcome barriers. By drawing on participatory insights from workshops across Ireland, this research seeks to map the emerging themes, challenges, and enablers of biodiversity finance in a national context. In doing so, it advances the literature by offering grounded, context-specific evidence on how finance can contribute to halting and reversing biodiversity loss.

3. Methods

Participatory Approach and Data Collection

To address our research question, we require rich, practice-informed insights on how sustainable finance can support biodiversity objectives across the island of Ireland. As the research is exploratory in nature a Participatory Research (PR) approach, involving a series of interactive workshops, has been deemed the most suitable mechanism to collect insights from key stakeholders. Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) state that PR “encompasses research designs, methods, and frameworks that use systematic inquiry in direct collaboration with those affected by an issue being studied for the purpose of action or change”. They also highlight that participants are not required to be trained in research, rather they should represent or be a part of the focus of the research. In this case, participants were all involved in fighting biodiversity loss, from an academic research perspective, directly through the practice of ecology, developing policies to aid nature conservation, or via the development of sustainable financial practices and practices. Vaughn and Jacquez (2020) also state that the research itself “can be conducted in a participatory, democratic manner that values genuine and meaningful participation”. A series of workshops that promoted engagement, using either Appreciative Inquiry (AI) or panel discussions, were therefore chosen as the tool with which data could be gathered in the form of insights, knowledge and experiences shared by participants. The PR approach is also advocated by Haatanen et al. (2014) and has been previously applied in research, such as a water quality study by Behmel et al (2018). Workshops are key to this PR approach and provide a valuable way to interact with stakeholders (Kok et al., 2006). The common aim of the interactive workshops conducted in this research was to gather stakeholder perspectives on the awareness of biodiversity loss, how solutions from finance can help address such loss and what can and should be done to advance this. The aim was also to highlight best practices, such as existing financial products that fund nature conservation, and to bring various disciplines together that share the goal of fighting biodiversity loss. Authors such as Perz et al. (2010) highlight that the literature advocates interdisciplinary, as well as international and interorganizational, collaboration for environmental conservation. Two of the workshops used the Appreciative Inquiry (AI) method, as described below.[1]

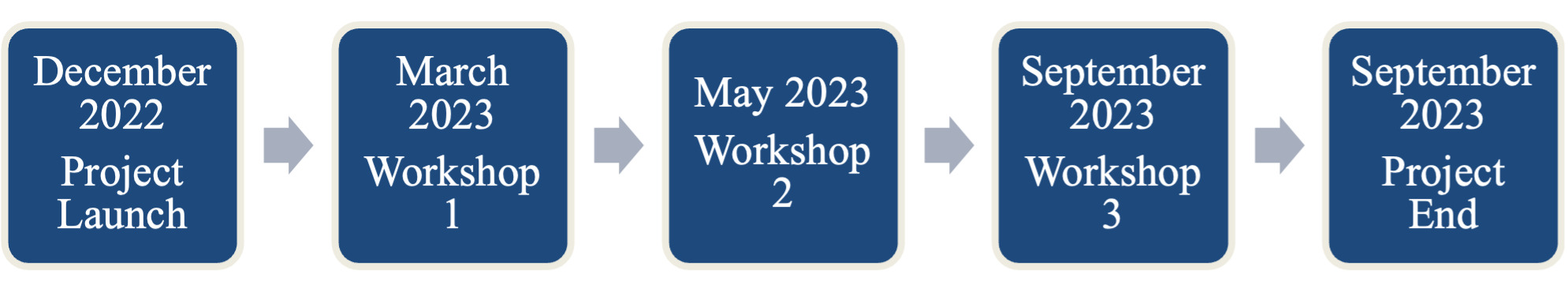

Three in-person workshops were held across Ireland during 2023, hosted by two different business schools and at the headquarters of one of the professional accountancy bodies, with an open invite distributed across the different faculties, financial institutions, government bodies, ecological organisations, and policy networks. In addition, a range of cross-sectoral keynote speakers were invited, which helped to frame the discussion. Figure 1 presents the timeline of the project.[2]

Each workshop lasted one full working day. Invitations were distributed widely across sectors through professional and institutional networks. Workshop formats were designed to maximise interaction and reflection and included keynote addresses from expert speakers, structured group discussions, and facilitated participatory activities. A total of 74 participants attended, including academics, ecologists, finance professionals, civil servants, non-governmental organisation (NGO) representatives, and advisors from both Ireland and Northern Ireland. (The list of the participants is provided in a table in Appendix A.) This diversity ensured a broad spectrum of expertise and sectoral perspectives. Table 1 presents detail on the keynote speakers at each workshop.

Appreciative Inquiry

AI was employed as a core participatory tool in two of the three workshops (Waterford and Belfast). AI was chosen because of its strength-based orientation in that it encourages participants to envision positive futures and identify enabling conditions for change (Bushe, 2007; Cooperrider & Srivastva, 1987/2013). In the context of this research, this method was particularly valuable in surfacing innovative ideas and uncovering best practices in biodiversity finance. AI was structured around four phases: discovery, dream, design, and destiny (Armstrong et al., 2020) – see Figure 2.

After the keynote speakers, participants were divided into small groups and asked to reflect on what they believe is already working in the context of biodiversity finance, what an ideal biodiversity finance landscape might look like, how to achieve that vision, and how to embed and sustain progress. Outputs included shared aspirations, solution pathways, and critical reflections on systemic barriers.

The third workshop, held in Dublin, followed a panel-led format with policy and business leaders. It focused on best practice via practical case studies and policy implementation challenges, which made the AI format less appropriate. Instead, insights were gathered through panel discussions, question and answer (Q&A) sessions, and plenary dialogue. This participatory, stakeholder-informed methodology was instrumental in generating grounded, practice-relevant insights into the evolving field of biodiversity finance in Ireland.

Scope of Discussions

The workshops were structured to explore how finance can support biodiversity objectives in Ireland. Participants were drawn from multiple sectors, including finance, policy, ecology, geography, and academia. The discussions ranged from global policy frameworks (e.g. the Kunming–Montreal GBF) to local issues such as hedgerows, community action, and peatland restoration. While keynote speakers provided framing context and examples, the facilitated discussions and group exercises enabled participants to reflect on their own knowledge and experience. Although the content of discussions was partly shaped by the speakers’ topics, participants actively co-created knowledge based on their sectoral perspectives. (The pseudonyms of the keynote speakers are included in Table 1. Participants in the AI workshops are denoted as AIB for Belfast and AIW for Waterford.)

Data Overview and Analysis

Across the three workshops, approximately 30 pages of detailed observational and discussion notes were collected, including facilitator observations, group feedback, and participant quotes. These notes have served as the primary dataset for analysis. Thematic analysis was applied to identify recurring patterns, concepts, and insights emerging from the discussions (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Analysis was undertaken manually, with iterative coding and comparison to ensure reliability and alignment with the research question. Particular attention was paid to the distribution and emphasis of themes across different categories of actors, including finance professionals, ecologists, academic researchers, policy representatives, and civil society organisations. For example, concerns about verification and additionality were more frequently raised by participants from financial institutions, whereas community embeddedness and ecological integrity featured more strongly in contributions from academics and NGO representatives. Thematic categories were refined across the three workshops to reflect cross-cutting priorities and consistency. While the aim was not to quantify inputs, the recurrence of key themes across diverse participants enhanced the robustness of the findings. The resulting themes are presented in Section 4.

4. Results

This section presents the key themes that emerged from the participatory workshops and discusses their implications in light of existing literature and the Irish context. Our aim is to foreground the voices and perspectives of stakeholders, while also examining how their insights reflect deeper structural, institutional, and cultural factors shaping the development of biodiversity finance in Ireland. While all seven themes were observed across workshops, concerns about verification and additionality, co-design with the agricultural sector, and community legitimacy were particularly emphasised. These themes appear to reflect Ireland’s regulatory context, the structure of land ownership, and the nascent stage of biodiversity finance in the country. Illustrative participant quotes for each theme are presented in Table 2, with a selection included in the text for emphasis.

Emerging Themes in Biodiversity Finance

Through a thematic analysis of workshop discussions, seven interrelated themes emerged that reflect the multifaceted challenges and opportunities in developing a functional biodiversity finance ecosystem. These themes reveal a growing convergence between ecological imperatives and financial innovation, while also highlighting the institutional, political, and cultural barriers to progress. Each is rooted in participant dialogue and resonates with ongoing debates in academic and policy literature.

Theme 1: Growing awareness but fragmented understanding

Unsurprisingly, the importance of nature was cited by the policy makers, academics and financiers, in particular the causes of the crisis in nature, mistakes made and how the financial sector is more cognisant of this now.

“Biodiversity loss is driven by our growth model. It’s important we question this model; loss of species has a negative impact on the economy; financial sector now taking this into account.” (MHE)

Specific recognition of the scale of the problem was referenced by both an ecologist and financial services providers, from a macro to a more micro level, with Ireland’s ambition to tackle the problem also surfacing. However, this recognition emerged as uneven as the discussions evolved, with one ecologist stating “we know very little about biodiversity loss … outside of the red lines” (Ecol2). Compounding this is the nature of biodiversity itself, which results in a gap in understanding, referred to by some participants as both an economic and an ecological concern. The importance of education in bridging the information gap about biodiversity was raised in all workshops, with a change in the cultural mindset and need for climate literacy also alluded to.

Theme 2: Intersections and tensions between climate and biodiversity

The intrinsic link between biodiversity and climate, despite participants displaying more knowledge of the latter issue, was raised, with a subsequent discussion of the real-world tensions where climate action may inadvertently harm biodiversity.

“Biodiversity interacts with climate change but there are trade-offs between them.” (Econ)

Explicit examples of these trade-offs were provided in all workshops, including a range encompassing the use of forestry, peatlands, marine, soil, agriculture and urbanisation.

These tensions are especially relevant in Ireland, where climate policy, particularly regarding land use, afforestation, and offshore wind, is rapidly evolving, often without parallel frameworks to safeguard biodiversity. Participants expressed concern that climate action plans may unintentionally lead to such trade-offs if nature-specific criteria are not fully integrated.

Theme 3: Making the business case for biodiversity

Participants widely acknowledged that the positioning of biodiversity as a value proposition, but also as a societal good, is essential for mobilising private capital.

“Business should care about biodiversity loss … due to its impact, dependencies on it, the risks and opportunities it presents too” (BPL)

Specific examples of opportunities for businesses mentioned ranged from monetizing Ireland’s peatlands to devising a nature credit for investors, the latter also having non-pecuniary benefits. Opportunities for Ireland’s agricultural sector were also raised, given its importance (“it accounts for 70% of the landscape, most privately owned” (Ecol2)), particularly embracing more sustainable farming methods such as those implemented in the Netherlands. Referred to as a “holistic land management practice” (SPL) this would benefit all parts/elements of the food chain. However, the challenges to the creation of a value proposition were evident due to the difficulties in valuing biodiversity and the lack of comparative data for businesses.

The challenge of monetising biodiversity was seen as particularly acute in Ireland due to the small scale of projects, fragmented land ownership, and limited investor familiarity with nature-based instruments. While participants referenced international examples, they also noted the need for bespoke Irish approaches that account for these constraints.

Theme 4: Role of financial institutions and product innovation

There was consensus that the private sector has an important role to play in plugging the nature biodiversity finance gap. Financial institutions (banks, insurers, and investors) must take a more active role in designing and delivering biodiversity-relevant financial products. Biodiversity credits were cited as a relevant product for investors, but views on this instrument were mixed.

“The Nature Finance Gap … we urgently need to double investment in nature by 2030 … it needs to come from the private sector.” (NBL)

Examples of best practice in suitable financial products were provided by two of the keynote speakers from financial institutions, as well as the need for blended finance and a partnership approach with government and other stakeholders.

However, most participants believed that the financial sector is still in the early stages of responding, with innovation largely limited to pilot projects, and that solutions from sustainable finance need to be more accommodating. The paucity of solutions at a policy level was also raised as an impediment, along with the lack of a skill set for developing suitable products.

Theme 5: Investor confidence, value, additionality, verification

Participants repeatedly flagged the challenges in building investor confidence in biodiversity finance. These ranged from the immaturity of biodiversity as an asset class for investors, its unique income stream resulting in uncertainty about its value creation potential, calculating additionality, and comprehension of the principles underpinning responsible investment in natural capital.

The monitoring and verification process is crucial to instilling investor confidence in biodiversity-related projects, which participants cited as important because this involves an independent assessment to check the accuracy and validity of claims made. While important to allay investors’ fears, participants described such assessment as costly. Without clear metrics and verification processes, the risk of ‘greenwashing’ was seen as high, potentially undermining trust and stalling investment, while the absence of scale for investors, particularly institutional investors, was referred to as a deterrent to investing in biodiversity-related projects. An additional complication for investors cited is the individualised nature of each project requiring tailor-made solutions, while the need for adopting a long-term view given the duration of projects also exacerbated the challenge for investors. Yet, despite these challenges, there was some evidence for a growing interest of investing in biodiversity-related projects for both pecuniary and non-pecuniary reasons, with technology, such as geospatial monitoring of nature-related projects, playing a role in this.

This theme resonated strongly with participants from financial backgrounds, reflecting the early-stage nature of biodiversity investment in Ireland. Unlike carbon markets, Ireland lacks a robust verification infrastructure for nature outcomes, which participants viewed as a critical barrier to credibility and scale.

Theme 6: Co-design with agriculture and business

Participants stressed that biodiversity finance must be designed in conjunction with key economic actors, especially farmers, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and land managers. The importance of incentives as part of the co-design was also mooted.

“Farmers need to be at the centre of the transition … more needs to be done to help them mitigate the financial and operational risks necessary to make changes.” (Econ)

Ireland’s large agricultural footprint, and its cultural and economic centrality to rural life, mean that co-design with farmers is seen as a prerequisite for legitimacy. Several participants argued that biodiversity finance in Ireland cannot succeed without aligning with existing agri-environmental schemes and local incentives.

Theme 7: Community embeddedness and local delivery mechanisms

Finally, participants identified local communities as essential to the success and legitimacy of biodiversity finance. Societal appreciation of nature, trust, familiarity, and local knowledge were highlighted as critical enabling factors.

“From schools to local community to resident association to gardens and sport complex … more people are engaging with nature.” (Ecol1)

Credit unions (“a highly respected brand” (AIW)), co-operatives, and other community finance structures were referenced as underutilised but promising intermediaries. This aligns with recent Irish Government and EU policy interest in place-based finance models and social-value investing.

Despite the increasing salience of biodiversity in global policy (e.g. SDGs, the GBF), participants noted that this awareness often fails to translate into tangible commitments from governments, businesses, and financial institutions.

From Themes to Propositions

These seven themes culminated in a series of propositions that synthesise participant views on the conditions for effective biodiversity finance. These were developed iteratively across workshops and reflect the lived experience of those working in this area:

-

There is widespread awareness of the biodiversity crisis, but also an urgent need for improved education and communication.

-

Biodiversity and climate goals are deeply intertwined, yet often in conflict: integrated strategies are needed.

-

Market-based biodiversity finance requires better metrics and compelling business cases.

-

Financial institutions must develop products tailored to biodiversity, particularly for agriculture and SMEs.

-

Additionality, transparency, and robust verification are essential to investor confidence.

-

Farmers and businesses should be actively involved in co-designing biodiversity finance instruments.

-

Local community engagement is critical to project legitimacy, uptake and success.

5. Discussion: Towards a Transformative Biodiversity Finance Ecosystem

This study seeks to explore how finance can support biodiversity objectives in a national context, using Ireland as a case study. Our findings build on and deepen the literature by offering grounded, stakeholder-informed insights. Rather than treating finance as a technical fix, participants framed biodiversity finance as a systemic challenge requiring cultural change, institutional innovation, and meaningful collaboration. Three cross-cutting insights emerge from our research:

Finance Must Be Locally Grounded and Socially Embedded

Participants consistently emphasised the importance of trust, community engagement, and cultural context in delivering biodiversity finance. These findings align with growing recognition that place-based and locally adapted finance models are critical to environmental outcomes (Garvey et al., 2024; Hill et al., 2025). Participants viewed biodiversity as deeply rooted in local identities, ecosystems, and agricultural landscapes, and believed that solutions must reflect these realities. This insight also speaks to challenges of legitimacy and uptake. Participants cited credit unions, co-operatives, and community finance mechanisms as underutilised but promising delivery vehicles. This supports Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria’s (2017) argument that community involvement enhances the legitimacy of biodiversity initiatives. It also aligns with recent EU and UN initiatives advocating for socially inclusive, participatory finance in nature-based solutions.

A Just Transition Requires Collaboration Across Sectors

A recurring theme was the need for co-design between finance professionals, farmers, and small businesses. Participants stressed that biodiversity finance tools must reflect operational realities on the ground, for example through farm-level advice, tailored incentives, and blended finance that shares risk. This emphasis on inclusivity echoes the “nature-inclusive agriculture” model developed by the central bank of the Netherlands and resonates with the participatory ethos advocated by O’Rourke and Finn (2020). It also aligns with Nedopil’s (2023) principle that biodiversity finance must account for local risks and opportunities to close the finance gap effectively.

Moreover, the importance of agricultural engagement links with the broader concept of a just transition: the need to ensure that ecological policies are not imposed top-down but developed in partnership with those most affected. This insight underscores that social justice and ecological resilience are mutually reinforcing.

Measurement Challenges Remain a Major Barrier

Participants identified verification, additionality, and outcome measurement as persistent bottlenecks to scaling biodiversity finance. These concerns mirror ongoing debates in the literature around the difficulty of quantifying biodiversity-related risks and benefits (Karolyi & Tobin-de la Puente, 2023; Metrick & Weitzman, 1998). Unlike carbon markets, biodiversity lacks standardised metrics, making investor confidence and regulatory oversight more difficult to achieve. Several participants called for stronger independent assurance and improved transparency to avoid greenwashing. While emerging frameworks like the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TNFD) offer guidance, they are often perceived as complex or inaccessible for smaller organisations—reinforcing the need for simplified, scalable tools. Our findings confirm that overcoming these measurement barriers is not merely technical but institutional and cultural: it requires aligning scientific, policy, and financial communities around shared standards and incentives.

6. Conclusion

This study contributes to the emerging field of biodiversity finance by identifying and analysing key themes from participatory workshops conducted across Ireland in 2023. Using a participatory research approach and AI techniques, stakeholders from finance, policy, ecology, geography, and academia were engaged to explore how sustainable finance can support biodiversity goals. Our findings reveal seven interrelated themes that highlight both the urgency of the biodiversity crisis and the complexity of mobilising financial solutions in response. The study addresses a recognised gap in the biodiversity finance literature, which remains relatively underdeveloped at the national level (Flammer et al., 2025; Nedopil, 2023). By focusing on Ireland, a country with growing policy ambition but limited academic attention in this domain, we provide new empirical insight into how context-specific institutional, cultural, and stakeholder dynamics shape biodiversity finance pathways. In doing so, we advance understanding of how sustainable finance can align with ecological goals within particular policy environments.

The study makes three core contributions. First, it provides empirically grounded insights into how finance practitioners, policymakers, and other actors conceptualise biodiversity finance in the Irish context. Second, it reinforces the need for finance solutions to be socially embedded, co-created with key stakeholders such as farmers and communities, and underpinned by clear, measurable outcomes. Third, it underscores the ongoing challenge of integrating biodiversity into financial markets in a way that ensures additionality, investor confidence, and ecosystem integrity.

Our findings identify several priorities for theory, policy, and practice. For theory, the study highlights the need for more empirical, context-sensitive research that moves beyond high-level frameworks to examine how biodiversity finance mechanisms operate in practice. Future work could explore how principles such as co-design, verification, and community legitimacy interact in different national contexts, and how these shape the scalability and credibility of financial instruments. For policy and practice, our results suggest that financial institutions must be supported in developing new instruments that align biodiversity outcomes with investment criteria (Theme 5: Investor confidence, value, additionality, verification). Policymakers should strengthen regulatory frameworks for additionality and verification (Theme 5), while also fostering co-design mechanisms across sectors (Theme 6: Co-design with agriculture and business). Community engagement (Theme 7: Community embeddedness and local delivery mechanisms must be central to project design and delivery to ensure legitimacy and long-term impact. Ireland’s growing sustainable finance infrastructure and legislative commitments position it well to lead in this space, particularly as biodiversity becomes more prominent in global finance.

This paper has some limitations. First, our findings captured the perceptions of participants at a particular point in time, which may not fully reflect the dynamic and evolving nature of biodiversity policy and finance. Second, although the workshops aimed to gather a diverse cross-sectoral group, the participant pool was weighted towards academic researchers and students, with fewer private-sector finance professionals. While some financial practitioners were present, future research would benefit from more targeted engagement with institutional investors, commercial banks, and financial intermediaries to capture a broader range of market perspectives. Third, we did not explore the governance structures or regulatory environments required to catalyse flows from the private sector into biodiversity finance. Finally, while our keynote speakers provided valuable examples of best practice, these were mostly focused on agriculture, forestry, and peatlands.

Future research should build on this exploratory work by conducting longitudinal studies of biodiversity finance initiatives, evaluating the effectiveness of financial instruments in delivering ecological outcomes, and further exploring investor behaviour and market responses. Comparative studies across jurisdictions and additional sectors such as marine or urban infrastructure would also help to clarify the enabling conditions for effective biodiversity finance.

In advancing understanding of how sustainable finance can address biodiversity loss, this study responds to recent academic calls (e.g. Flammer et al., 2025; Karolyi & Tobin-de la Puente, 2023; Nedopil, 2023) for more context-specific, participatory, and interdisciplinary research in this evolving domain. It provides a foundation for future inquiry and policy development and contributes to the broader goal of aligning financial systems with the urgent need to protect and restore nature.

.png)

.png)