1. Introduction

“As the Jesuits knew far too well, pursuing only profit is amoral and makes us sinners, but one cannot pursue God without the appropriate financial resources. The Jesuits were indeed advanced when discussing externalities and issues of integration!” (Quattrone, 2022, p. 556). This observation by Quattrone (2022) highlights a timeless paradox that resonates in contemporary debates on sustainability and accounting. The Jesuits’ understanding of the moral implications of profit, as well as their early discussions on externalities, reflects a core tension in modern organizational practices: how to balance financial pursuits with ethical and social responsibilities. Today, this intersection between accounting and sustainability continues to catalyze a dialectical[1] debate, both academic and practical in nature.

At the heart of this discourse lies the well-known maxim “if you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it” (Micheli & Mari, 2014, p. 5), raising questions about the relationship between measurement, management, and disclosure of organizational performance. While the pursuit of profit and a focus on tangible metrics may seem like clear strategies for organizational success, such an approach can obscure essential qualitative aspects of sustainable performance (Braam & Peeters, 2018; Jørgensen et al., 2022; Schaltegger & Wagner, 2006). Indicators such as carbon emissions and energy efficiency can be measured directly and objectively (Gyamfi et al., 2021; Qian et al., 2018), but dimensions such as employee well-being, community impact, resource scarcity, and gender equality often fall outside these measurable criteria. These qualitative dimensions are just as important but difficult to quantify and integrate into traditional accounting systems (Adams et al., 2020).

The complexity of these dimensions challenges linear, monetary-based approaches, making it difficult to fully capture their interconnections and influence (Schaltegger & Wagner, 2006). As a result, organizational performance reports often lack transparency (Caputo et al., 2021; Quattrone, 2022) and reflect limited accountability (Melloni et al., 2017; Talbot & Boiral, 2018). This creates an information asymmetry between the organization and its stakeholders (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2017; Hickman, 2020), leading to a distorted or incomplete representation of true organizational performance, often limited to isolated activities that fail to fully capture broader challenges and impacts (Bebbington et al., 2020; Oliveira et al., 2023).

To address these challenges, significant theoretical and practical advances have been made. Previous reviews have provided valuable insights (Hörisch et al., 2020; Patten, 2020; Velte & Stawinoga, 2017) and demonstrated empirical progress in areas such as environmental accounting, sustainability accounting, and sustainability reporting (Bebbington & Larrinaga, 2024; Burritt et al., 2023; Qian et al., 2018; Schaltegger et al., 2022). This includes the development of sustainable performance measurement systems (Searcy, 2012) and the integration of social and ecological concerns into management and incentive systems (Eccles et al., 2014; Schaltegger & Zvezdov, 2015).

Studies have also explored how structural representations and corporate responsibility relate to organizational performance (Cho et al., 2015; Clune & O’Dwyer, 2020; Gibassier et al., 2018; O’Dwyer & Unerman, 2016; Tregidga & Milne, 2022). Furthermore, meta-analyses have also examined the relationship between environmental management systems and organizational performance (Nogueira et al., 2023), the impact of environmental performance on financial outcomes (Hang et al., 2019), the connection between corporate social responsibility (CSR) performance and stakeholder value (Samet et al., 2022), as well as the integration of supply chains in sustainability performance (Wang et al., 2022).

Despite these advances, challenges remain in effectively integrating sustainable dimensions into organizational performance in a comprehensive way (Arjaliès et al., 2023; Gond et al., 2012; O’Dwyer & Unerman, 2020; Parisi, 2013). To address these issues, we conducted a systematic review of accounting literature (Hiebl, 2021, 2023; Quinn et al., 2023), which included bibliometric and content analysis of 704 articles. This review not only underscores the existing challenges but also identifies opportunities in the field. A key focus of this study is the question: How can accounting practices evolve to effectively integrate sustainable dimensions into organizational performance? Addressing this question is critical to bridging the gap between traditional financial metrics, which often have a narrow scope, and the complex socio-environmental issues organizations face today. Accounting practices, therefore, need to reinterpret corporate sustainability, fully incorporating financial, social, and environmental dimensions into organizational performance (Adams et al., 2020; Arjaliès et al., 2023).

Our contribution to this discussion is twofold. First, we expand the literature on the intersection of accounting and sustainability through a systematic review. By applying bibliometric and content analysis, we explore four key propositions, organized into clusters: development, innovation, governance, and accountability. Each cluster reflects distinct organizational challenges and opportunities, characterized by different business models, respectively: focused on priorities, adaptable to context, structured for compliance, and integrated for effectiveness. Achieving sustainable performance depends on balancing and integrating these models within organizations. Our propositions emphasize the need to consider each organization’s unique complexities in promoting sustainability. Sustainable performance is achieved by aligning these models with organizational moderating factors such as purpose, planning, actions, and results.

Second, we purpose the concept of ‘accounts that matter’, inspired by external accounts (Angotii et al., 2024; Perkiss et al., 2021), representing an alternative to traditional accounting practices by addressing not only financial data but also challenging situations within organizations, contextualized through a framework to interconnect clusters. While the intersection of accounting and sustainability sparks vital debate, simplistic approaches that focus solely on financial metrics fail to capture the complexity of integrating sustainable practices into organizational performance.

Our framework illustrates how sustainable performance requires a multidimensional approach. We argue that accounts – strategic accounts, relationship accounts, operational accounts, resource accounts – must evolve to embrace this pluralism, fostering a balance between autonomy and collaboration, as well as flexibility and control within these clusters, enable organizations to address complex issues and transform their practices in meaningful, sustainable ways. Finally, we conclude with reflections on existing gaps in the literature and propose directions for future research. Our aim is to improve the implementation of accounts and enhance their contribution to achieving truly sustainable organizational performance.

2. Research Methodology

To investigate the complex intersection between accounting and sustainability, a methodological systematic review approach was adopted (Hiebl, 2021, 2023). This approach was underpinned by bibliometric and content analyses, starting from a meticulous selection of databases (Franceschini et al., 2016; Martín-martín et al., 2018) and search terms (Chen et al., 2021) to the statistical modeling of relevant content in sets of articles (Jelodar et al., 2019; Zou et al., 2018). It comprises three distinct phases: ‘planning the review’; ‘conducting the review’; and ‘reporting and dissemination’ (Tranfield et al., 2003).

The first phase – planning the review – encompassed the identification of relevant constructs (Tranfield et al., 2003). With this phase in mind, an initially unstructured application used a snowballing[2] technique to capture a broad view of the field that resulted in the formulation of the research question: How can accounting practices evolve to effectively integrate sustainable dimensions into organizational performance? With this research question as the foundation, the paper selection process was designed to ensure a comprehensive and focused review of relevant literature, which guided the entire subsequent review through rigorous criteria for the selection of articles (Tranfield et al., 2003).

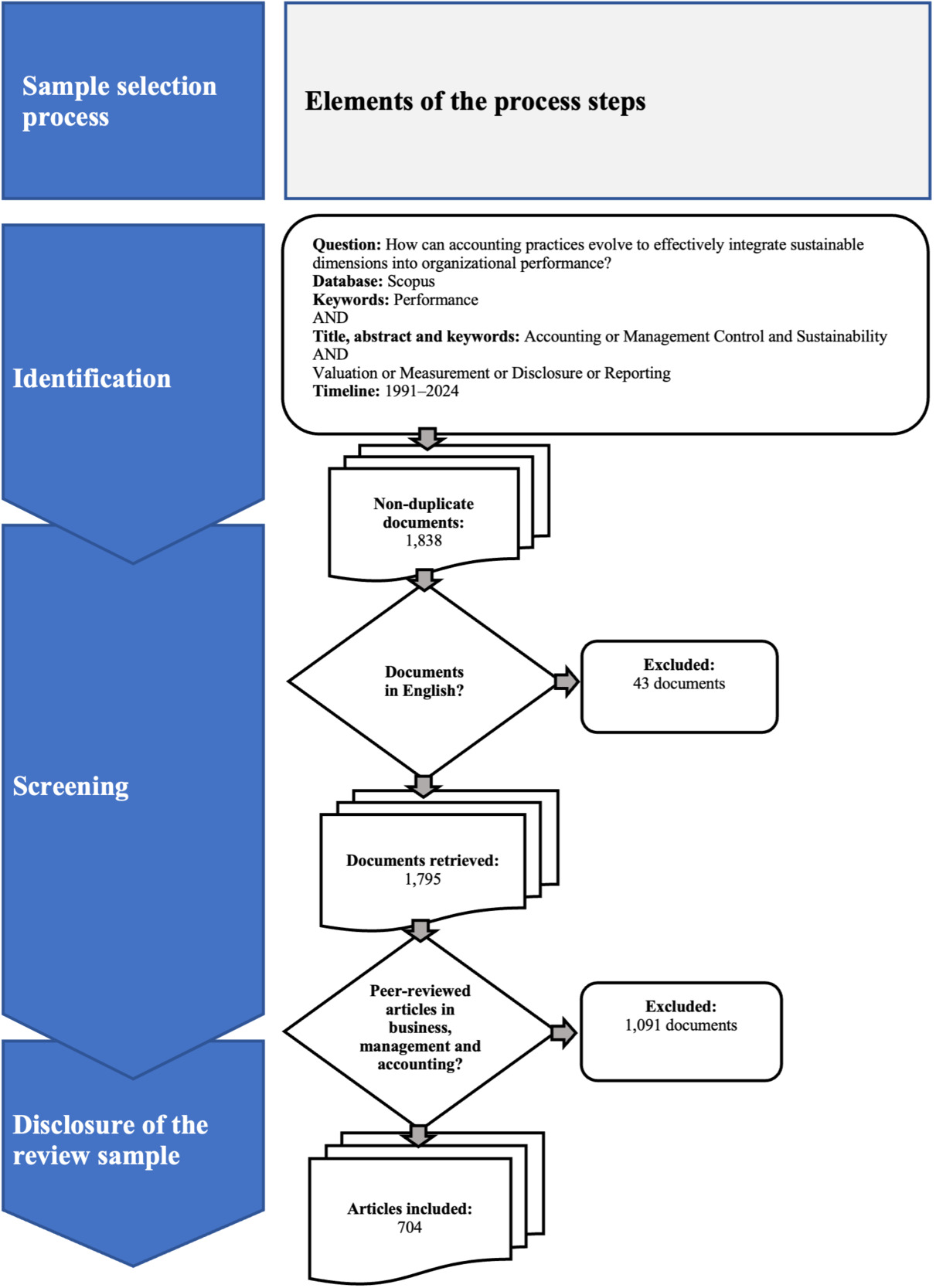

The paper selection process, described in Figure 1, was planned to ensure that the review was comprehensive and accurate. It began with the clear definition of inclusion and exclusion criteria, essential to ensure that only relevant and high-quality articles were considered for the review (Hiebl, 2021), which involved choosing the appropriate academic database. The Scopus database was selected, known for its breadth and utility in bibliometric analyses and content modeling (Franceschini et al., 2016; Martín-martín et al., 2018). The initial collection followed criteria based on the research question and included searching for terms ‘Accounting’ or ‘Management Control’ and ‘Sustainability’ along with ‘Valuation’ or ‘Measurement’ or ‘Disclosure’ or ‘Reporting’ in the title, abstract, and keywords, resulting in 1,838 documents.

Subsequently, the search was refined to include only academic articles in the English language, which led to the exclusion of 43 documents in other languages, thus maintaining the cohesion and accessibility of the data set. We limited inclusion to peer-reviewed research articles published in the fields of ‘Business, Management, and Accounting’, focusing on contributions of high quality and relevance to the research (Chen et al., 2021). This criterion resulted in the exclusion of 1,091 documents. The bibliographic records of the remaining articles were extracted and converted to CSV format, facilitating deeper analyses. Adapted from the model by Hiebl (2021), Figure 1 details the sequence of identification, filtering, and selection of documents up to the formation of the initial sample for analysis.

With the dataset refined and converted, the second phase of the systematic review – conducting the review – focused on analyzing the results (Tranfield et al., 2003), which sought a balance between the depth of analysis and clarity in presentation, using charts and tables (Hiebl, 2021). Section 3 is dedicated to describing the results obtained from the initial sample of 704 articles. The use of tools such as RStudio version 4.3.2, bibliometrix (Aria & Cuccurullo, 2017), and VOSviewer facilitated the analyses (Liao et al., 2019). It initially consisted of a bibliometric analysis, including a general assessment of the most influential journals, key authors, leading institutions, and the main thematic topics. Following this overview of the initial paper sample, more in-depth discussions are presented on the essential components – or clusters – of sustainability, detailed in Section 4.

Section 5 includes the stratification of the initial sample into 123 reviewed articles, using content modeling through cross-analysis to map co-citations, collaborations, and keyword co-occurrences, providing insights into the structure and emerging trends of the field (Hiebl, 2023). Building on the initial bibliometric insights, the content modeling further explored the relationships between key concepts, grouping the articles into thematic clusters for a more detailed and organized understanding of the evolution of the field of study in question (Jelodar et al., 2019). The primary challenge encountered in this phase was balancing the level of detail with ease of understanding. Initially, the selected articles were disaggregated into specific topics. Subsequently, these topics were grouped into clusters, allowing for a more in-depth and structured understanding of the field’s evolution.

Finally, the last phase – reporting and dissemination – discussed in Section 6 underpins important integration with clusters, mapping gaps and opportunities (Hiebl, 2023; Tranfield et al., 2003), which contributed to the theorical conceptual framework of the ‘accounts that matter’, facilitating the formulation of future directions, concluded in Section 7.

3. Result of Bibliometric Network Analysis

The consolidated data presented in Table 1 summarize the relevant information from the selected articles published between 1991 and 2024. In total, 704 articles met the criteria for the initial sample selection. These papers involved 1,496 authors and included 40,276 bibliographic references. The citation analysis reveals an average of 39.14 citations per article, with an annual frequency of approximately 5.9 citations. A more detailed analysis of the authorship of the articles indicates a clear predominance of collaborative efforts. Of the articles analyzed, only 116 were written by a single author, while the remaining 588 were produced by teams of multiple authors, resulting in a collaboration index of 2.57. These data, organized in Table 1, provide a quantitative overview of the characteristics of peer-reviewed scientific production in the field of study in question, emphasizing the importance of academic contributions in this area of research.

3.1 Timeline of Most Publications and Citations

Figure 2 illustrates the trajectory of publications on the theme from 1991 to 2024, highlighting significant growth interspersed with fluctuations. The initial period, from 1991 to 2005, is characterized as the embryonic phase with a modest volume of publications. Between 2006 and 2014, there is a marked acceleration in the number of research papers, reflecting a growing academic interest in this field of studies.

The consolidation phase extends from 2015 to 2024, with the years 2020 to 2023 showing steady production, despite a slight contraction in 2021 due to the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on editorial processes. These data, which include peer-reviewed articles until February 2024, provide an updated overview and reveal recent challenges faced by the field. The evolution of research reflects an increase in the discussion of integrating environmental and social pillars into corporate decisions, moving from a focus primarily on financial metrics to an approach that also encompasses environmental and social performance. Research in sustainability and accounting practices began to emerge as a direct response to growing global environmental concerns and calls for increased corporate accountability.

In the early years, or embryonic phase, studies focused on how companies could internalize intangible and external environmental costs into their traditional financial statements. Notably, the seminal work of Leif Edvinsson in 1997 on the intellectual capital valuation model and the study by Jan Bebbington and Rob Gray in 2001, which reconceptualized sustainable cost calculation, were highly cited over time (Bebbington & Gray, 2001; Edvinsson, 1997). Articles such as those by Gray and Bebbington (2000) and Milne (1996) pioneered the exploration of how accounting practices could reflect environmental impacts, marking the beginning of awareness of the need for integration between accounting and sustainability (Gray & Bebbington, 2000; Milne, 1996). This period also saw the introduction of initial standards and guidelines for sustainability reporting, although adoption by companies was still nascent and often seen as a public relations initiative rather than a substantive integration into decision-making processes (Lamberton, 2005).

An expansion phase (2006–2014) was characterized by rapid growth in the literature, with an expansion of the research field and critiques from the academic side (Adams, 2008; Gray, 2006), as well as greater adoption of sustainability practices by organizations (Pedrini, 2007). This period witnessed increased institutionalization of sustainability reporting, driven both by stricter regulations and by a recognition of the strategic value of sustainability (Gond et al., 2012; Gray, 2010). Studies by Clarkson et al. (2011) and Eccles et al. (2014) illustrate how corporate governance began to incorporate sustainable concerns in a more integrated manner (Clarkson et al., 2011; Eccles et al., 2014), emphasizing the role of stakeholders in shaping corporate policies (Boiral, 2013). These developments underscored the need for organizations to balance financial objectives with broader environmental and social responsibilities. A pivotal aspect of this transition was the adoption of strategic frameworks such as the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Triple Bottom Line (TBL), which offered a structured approach to evaluating non-financial indicators alongside traditional financial metrics (Flower, 2015; Maas et al., 2016; Melloni et al., 2017). By integrating these frameworks, organizations began to adopt a more holistic perspective on performance, aligning sustainability goals with corporate strategy.

More recently, research into sustainability and accounting practices has reached a consolidation phase, marked by maturity with an increasing focus on innovation and responses to climate change. The emergence of recent technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and blockchain has provided opportunities to enhance the accuracy and transparency of financial statements. Articles such as those by Christensen et al. (2021) discuss how these technologies are being utilized to track and report the environmental and social impacts of corporate operations in real time (Christensen et al., 2021). Furthermore, current research is increasingly focused on how organizations can contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), reflecting critiques and a holistic and integrated view that encompasses ethics (Parfitt, 2024), environmental and social performance (Talbot & Boiral, 2018) and governance practices. In this context, Dillard and Vinnari (2019) critique the limitations of traditional accounting systems, which prioritize the needs of financial capital providers, and propose dialogic accountability[3] as an alternative account. This approach emphasizes the design of accountability systems that reflect the diverse and often conflicting evaluation criteria of multiple stakeholders, challenging conventional practices and expanding the boundaries of governance (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019), and as inseparable elements of dynamic capabilities[4] (Scarpellini et al., 2020) and modern corporate strategy (Haji et al., 2023). Together, these perspectives highlight the growing integration of sustainability into corporate strategies, setting the stage for actionable insights.

3.2 Top Journals and Most Productive Authors

Table 2 reveals the most productive journals dedicated to publishing research within the Scopus database. Of the 20 most active journals, 345 articles were published, accounting for 49.0% of the total dataset analyzed. These journals are associated with eight distinct publishers. Emerald Publishing stands out, responsible for nine of these journals. Subsequently, there is a broader distribution, with Elsevier, John Wiley and Sons, Academic Press, and Routledge each contributing two journals focused on the research theme. Springer, Sage Publications and DeGruyter complete the list, each with a single journal dedicated to the theme. This diverse distribution suggests a wide range of sources for accessing and contributing knowledge in this specific field.

Among the journals analyzed, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal stands out in terms of productivity, with 61 articles, representing approximately 17.7% of the total articles published in the leading journals of the field. Close behind, Journal of Cleaner Production features 53 articles (15.4%), while Sustainability Accounting Management and Policy Journal accounts for 50 publications (14.5%), along with other journals, forming a diverse list of key sources for the research field. Beyond the volume of publications, Table 2 also offers an evaluation of these journals’ quality, using metrics such as the H-index (based on Scopus citations), as well as rankings from the Scimago Journal Rank (SJR) and the ABDC Journal Quality List (JQL) for the year 2022. The latter categorizes journals into five levels of prestige (A*, A, B, C, and D). Of the 20 most productive journals, 11 (or 55%) are rated at the A* and A levels.

This variety of indicators provides a comprehensive view of the academic stature of the journals under analysis, facilitating a deeper understanding of the significance and impact of these publications in the research field concerning the theme. Furthermore, the research field has witnessed significant growth in terms of output, as evidenced by the impressive number of 1,496 authors who have contributed to the 704 peer-reviewed articles. This engagement is indicative of the theme’s relevance. Table 3 provides a detailed view of the 20 most productive authors in this field, listing their H-index from Scopus, along with their current affiliations and countries.

The arrangement of authors in Table 3 follows an order based on each author’s total publications. Leading the list as the most productive author, Stefan Schaltegger stands out with 13 papers and an H-index of 11, having begun his academic journey in 2006. His works have amassed 1,380 citations, recognized for his contributions in the field of corporate sustainability management, particularly in measurement, accounting, managerial control, and stakeholder engagement strategies. Warren Maroun, James Hazelton, and Sumit Lodhia follow him, each with eight articles and H-indices of 8, 7, and 6, respectively. Charl de Villiers also features with seven published works and an H-index of 6.

Rob Gray, despite having only five publications on the specific theme, is notable for his extensive academic contribution, amassing 1,876 citations since beginning his academic journey in 2000. Recognized for the depth and durability of his influence in the field (Parker, 2014; Rodrigue & Tregidga, 2020), Gray has developed foundational and critical perspectives in the area, such as the concept of ‘corporate responsibility’ focused on ‘intergenerational equity[5]’ (Bebbington & Gray, 2001).

Alternatively, Sabina Scarpellini and Alfonso Aranda-Uson emerge as the most recent contributors, having begun their production in 2020, and achieving 244 and 212 citations in six and four articles, respectively. They are included in the list of the top 20 authors, demonstrating significant impact in a brief time.

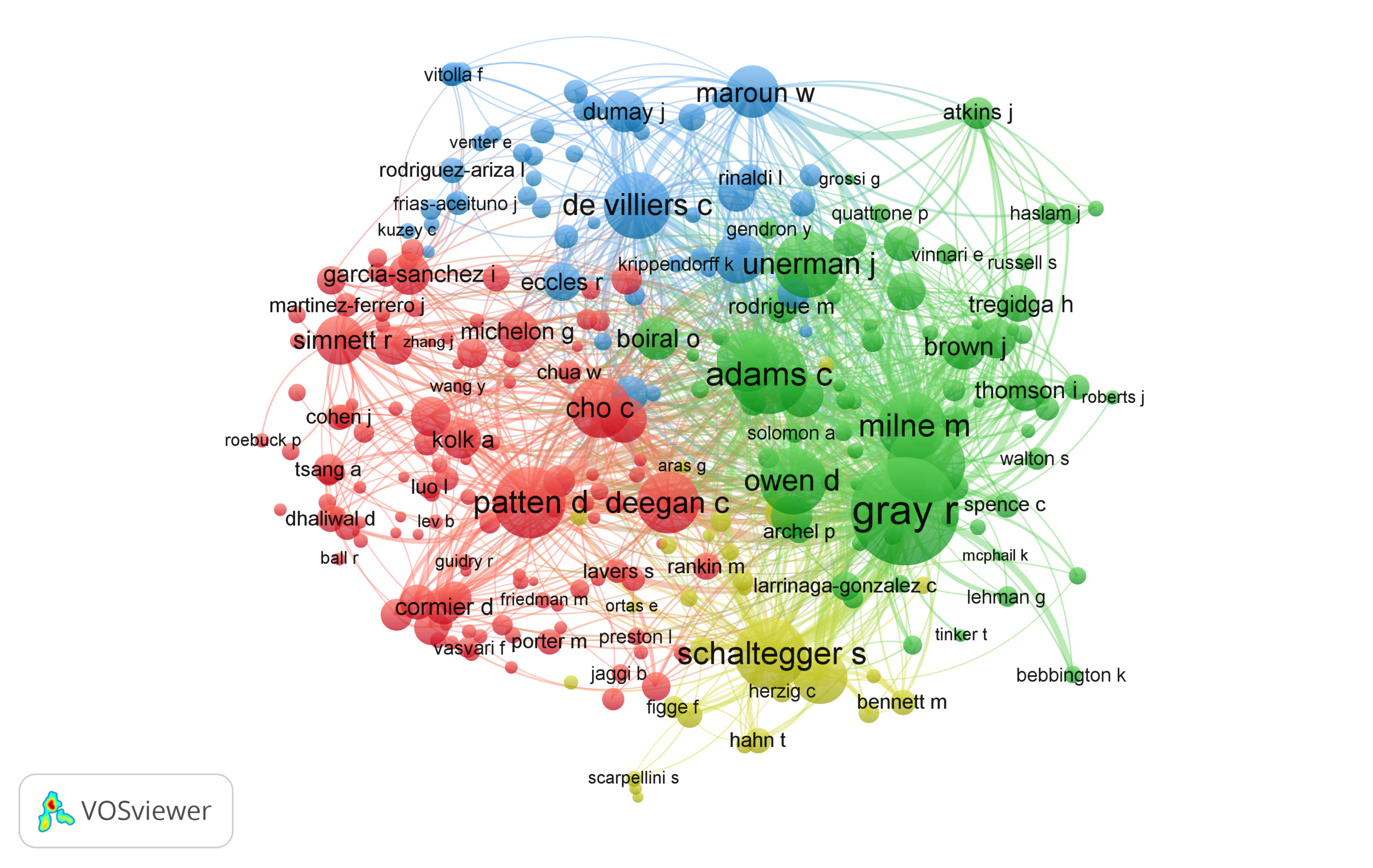

Figure 4 presents a network of co-cited authors in the research, generated by VOSviewer based on the 704 selected articles, where each author was cited at least 25 times. The analysis yields significant insights. The distribution of nodes indicates variation in terms of proximity and similarity between research fields, while the thickness of the lines between authors denotes the intensity of their relationships. Larger nodes indicate a central position in the author cluster, often considered influential and dominant (Chen et al., 2021). Authors such as Rob Gray, Carol Adams, Marcus Milne, David Owen, Jeffrey Unerman, Dennis Patten, Craig Deegan, Charles Cho, Stefan Schaltegger, Warren Maroun, and Charl de Villiers emerge as highly cited, underscoring their relevance in the academic community.

Finally, the analysis of Figure 4 also identifies four distinct groupings, with the red group being the most extensive, containing 120 authors, such as Dennis Patten, Craig Deegan, Charles Cho, Ans Kolk, Roger Simnett, Jennifer Martínez-Ferrero, among others significant in the context of the research. The green group includes 77 authors, featuring prominent figures like Rob Gray, Carol Adams, Marcus Milne, David Owen, Olivier Boiral, Paolo Quattrone, Jill Atkins, Helen Tregdiga, and Jeffrey Unerman. Additionally, the blue group, with 48 authors, hosts Warren Maroun, Charl de Villiers, and Michelle Rodrigue. Lastly, a yellow group, representing the more tenuous connections but no less significant, includes Stefan Schaltegger among its members.

4. Results of Content Analysis

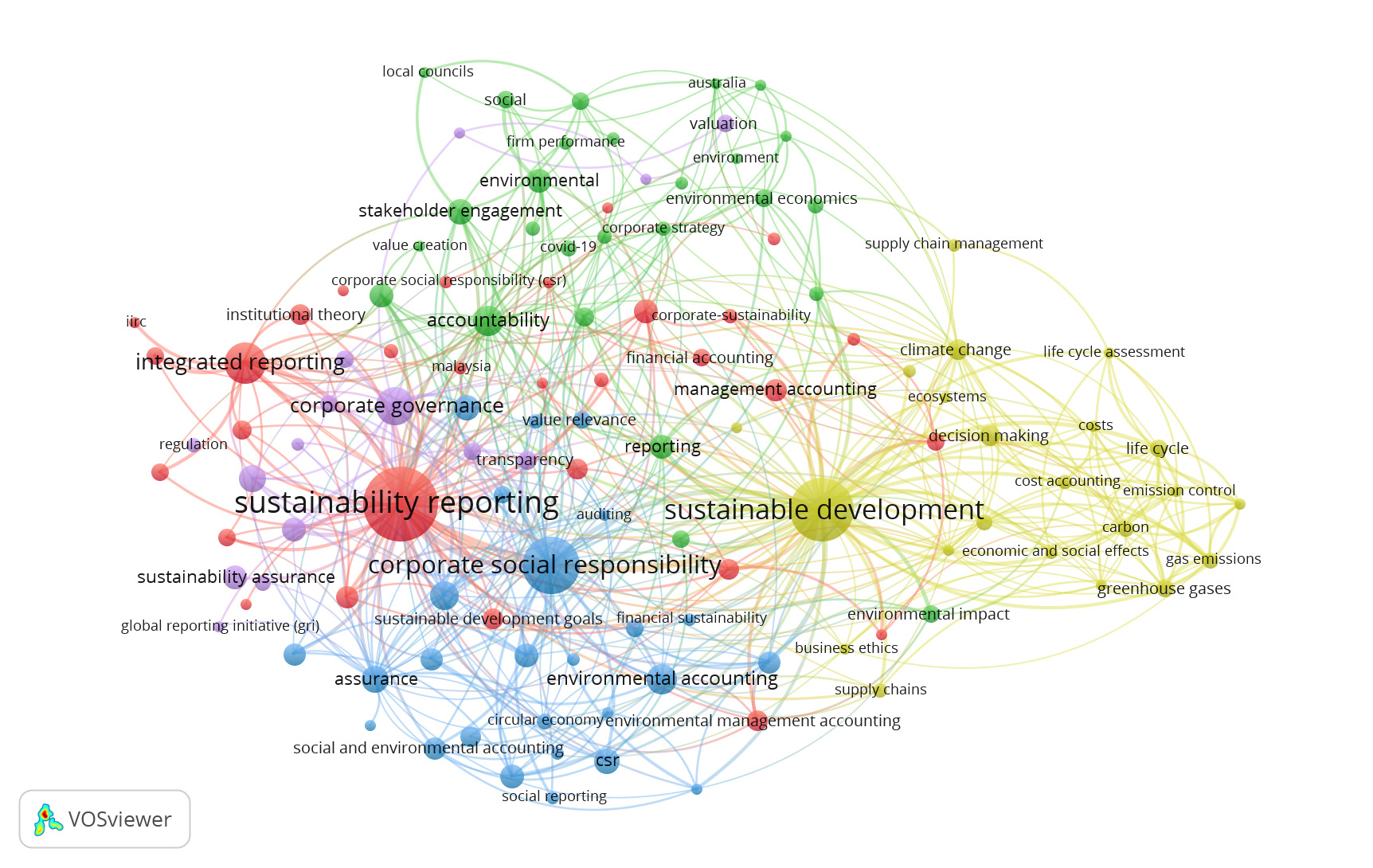

Having established an understanding of the principal publications, journals and authors, a content analysis deepens the examination of the co-occurrence network to solidify the connections between the bibliometric base and the content of previous studies. This analysis presupposes that the keywords selected by the authors effectively summarize the articles (Jelodar et al., 2019). The intensity of the connection between two keywords is determined by the frequency with which they appear together, with the total number of such occurrences indicating how common these combinations are (Liao et al., 2019). This method not only highlights the most relevant terms but also clarifies the connections between them in the studied context. Figure 5 illustrates these clusters and connections among different topics in the bibliometric network.

Figure 5 also signals the pillars of growing interest and intensive investigation in the research. It suggests that the increase in frequency and evolution of these keywords over time reveals which themes have dominated discussions and research in the field of accounting, pointing to fruitful directions for future studies. The interrelationship between these keywords not only traces the development of the field but also underscores the areas that may define the research agenda in the coming years (Liao et al., 2019).

4.1 Techniques and Analytical Approaches

In the digital age, processing and analyzing large volumes of data is essential for understanding complex phenomena. In the research context, clearly defining the scope of a study provides a solid methodological foundation for exploring themes and patterns within large sets of textual data (Hiebl, 2023). Techniques such as TF-IDF (Term Frequency-Inverse Document Frequency) and LDA (Latent Dirichlet Allocation) play crucial roles in this process, each serving a distinct function in identifying relevance and organizing the thematic structure of documents (Jelodar et al., 2019). TF-IDF method measures the relevance of a term by calculating its frequency relative to other terms in the dataset. It quantifies how often a term appears in a document compared with the total corpus, highlighting key terms central to the core themes of the text. In contrast, LDA groups terms based on co-occurrence, organizing them into broader topics. LDA models the relationships between terms, allowing researchers to visualize how documents relate within a thematic framework (Jelodar et al., 2019).

Figure 6 presents a detailed analysis of the 25 most relevant topics identified from the sample of 704 articles. These topics were extracted using the TF-IDF methodology, which measures the relevance of terms within the corpus, while the LDA model grouped these terms into coherent topics. The radar chart displays the average beta (β) value for each of these topics, reflecting the probability that certain words are strongly associated with specific topics. Each point on the chart represents the average contribution of terms to their respective topics, as identified by the LDA. Higher beta values indicate a stronger association, suggesting that these terms are more central to the themes represented. Thus, Figure 6 not only visualizes the distribution of these topics but also reveals the academic areas where the literature is most concentrated, highlighting the most significant contributions to the field of study. The diversity of topics, ranging from technical accounting processes to ethical, social, environmental, and governance issues, underscores the interdisciplinary nature of the study. Understanding how different disciplines intersect through these topics provides a foundation for a broader, more holistic approach to the themes addressed in these articles. This cross-disciplinary approach is crucial for interpreting the complexity and depth of the research field under review.

4.2 Delimiting the Content Analysis: Dimensional and Cluster Interpretation

Table 4 details the main findings associated with each topic, crucial for guiding subsequent analysis, allowing for a more refined interpretation of the thematic patterns present in the reviewed research. The column ‘Article sampling by LDA’ in this table shows the volume of articles grouped by topic, which were highlighted as central to each group of documents. The Dim.1 and Dim.2 columns provide the median values (μ̃) of the two-dimensional factor scores for each topic, calculated based on the factor loadings that indicate the shared variance in two dimensions, allowing a more detailed understanding of how the variables correlate with each factor. In addition, the mean value or factor score for each dimension helps to identify more complex patterns among the variables, offering not only a comprehensive view of how these themes are distributed within the data set, but also a framework for interpreting their relevance.

Dim.1 is largely associated with terms that focus on regulatory practices and strategies for sustainable development. The analysis reveals business models that are focused and adaptive, underlining the importance of organizational planning to promote flexible and autonomous methods for pursuing development and innovation. This interpretation is further supported by the clustering of key terms such as social responsibility, circular economy, and business strategies, which illustrate how researchers conceptualize sustainability. The emphasis on flexibility and independence in Dim.1 reflects the critical need for organizations to strike a balance between adhering to regulatory requirements and maintaining the ability to innovate and adapt. In this context, flexibility refers to an organization’s ability to evolve in response to changing social, environmental, and market pressures, while independence highlights its capacity to pursue sustainability goals autonomously. This delicate balance leads to more resilient and dynamic organizational models, enabling businesses to meet stakeholder expectations effectively while keeping sustainability at the forefront of their strategy.

By contrast, Dim.2 is primarily focused on terms related to governance, compliance, and control mechanisms within sustainability frameworks. The analysis points to business models that are structured and integrated, prioritizing actions to support control mechanisms and foster collaborative approaches to sustainable governance and accountability. This understanding is reinforced by terms such as ESG standards, social impact, and regulatory alignment, which demonstrate how researchers focus on ensuring transparency and accountability in sustainable operations. In Dim.2, the focus on control and interdependence is key to maintaining robust systems that ensure compliance with external regulations while promoting collaboration across different departments and stakeholders. This approach encourages the creation of sustainable strategies that are not only regulatory-compliant but also deeply embedded within the organization’s governance structures. As a result, organizations are better positioned to build long-term resilience and align themselves with both societal expectations and regulatory standards. Moreover, the dimensional analysis provides a deeper qualitative understanding of how these clusters – centered on Dim.1 and Dim.2 – form the basis of sustainable performance strategies across diverse organizational contexts.

Continuing this analysis, Figure 7, created using the bibliometrix package in RStudio, deepens the statistical investigation by providing a scatter plot that illustrates the distribution of the factorial scores of each key term, representing the clustering of studies and suggesting potential emerging clusters in the academic field. These clusters function as interconnected thematic categories or essential components of sustainability – development, innovation, governance, and accountability, as shown in Figure 7. Each of these studied clusters can act iteratively to facilitate the integration of financial, social, and environmental dimensions. This means that, while each cluster may operate independently at times, they all also influence each other within the context of studies on the intersection between accounting practices and sustainability. For example, a higher score in Dim.1 indicates terms studied with a more strategic focus on sustainable development and innovation. Meanwhile, Axis 2, corresponding to Dim.2, captures terms related to operational aspects of these previous studies. The higher the Dim.2 score, the greater the emphasis on the governance and accountability clusters. This scatter plot, therefore, provides a holistic view of how strategic and operational focuses are addressed in academic studies, highlighting the interdependent relationships between development, innovation, governance, and accountability in current discussions. The scatter plot also provides a visual representation of how the thematic categories of the previous studies are positioned within the clusters, providing crucial insights that can be analyzed in different contexts. For example, studies within the innovation cluster are positioned in the quadrant that combines high flexibility with strong control, indicating research that analyzes how organizations successfully integrate cutting-edge technologies with robust governance structures.

In comparison, studies in the governance cluster reveal relatively low scores in control and collaboration and moderate levels of flexibility. This suggests that these studies are situated in contexts where governance mechanisms are present but may lack strong enforcement and adaptive capabilities, potentially limiting their transformative potential. Studies in the development cluster, positioned in a more balanced zone of the diagram, reflect a study approach in which both flexibility and control are adequately addressed by researchers. Finally, studies in the accountability cluster, which have low scores in flexibility and autonomy but relatively high levels of control and collaboration, highlight study contexts that operate within rigid accountability structures. These contexts may face significant challenges, including a potential risk of obsolescence or loss of stakeholder trust due to their inability to evolve and maintain adequate governance practices.

Thus, the scatter plot in Figure 7 organizes previous studies into clusters according to the main topics analyzed by accounting and sustainability researchers. This diagram provides a clear view of how different aspects of the intersection between accounting practices and sustainability are addressed in the accounting literature, guiding this review to identify trends and gaps that need to be explored. Once the studied clusters had been defined, the next step was to understand, within the context of these previous studies that make up these four clusters, what the concept was attributed to and the scope of sustainable performance and how accounting practices could promote it.

5. Making Sense of the Literature

After a comprehensive bibliometric and content analysis, which included the evaluation of 704 articles, this systematic review had reached a crucial point. Up to this point, statistical tools had been employed to identify significant patterns and correlations within this extensive body of publications.

This section presents the qualitative criteria applied to stratify 123 articles, revealing insights obtained through the ‘cross-analysis’ methodology (Hiebl, 2023), which required a careful reading of the articles, with the aim of summarizing and integrating previous articles (Tranfield et al., 2003). This process enabled the construction of a robust theoretical foundation, essential for exploring how accounting practices can evolve to effectively integrate sustainable dimensions into organizational performance. Building on this foundation, the aim here is to clarify the challenges and identify emerging opportunities in the ongoing process of integrating sustainable practices.

To deepen the discussion on the challenges and opportunities at the intersection of accounting and sustainability, it was first necessary to synthesize the literature that addresses the identified clusters, the perspective, the arrangements, and the practices for integrating sustainable performance in business. Based on this synthesis, propositions were developed regarding how these clusters interact across financial, social, and environmental dimensions. Finally, a framework is presented, illustrating how accounting practices can act as facilitators of cluster, aiding the integration of sustainable dimensions into organizational performance, as revealed in the qualitative review.

5.1 Sustainable Performance is a Matter of Perspective

Performance, deeply embedded in modern societies, serves to assess both individual and collective efforts (Micheli & Mari, 2014). In organizational theory, performance reflects the core purpose of an organization (March & Sutton, 1997). To achieve success, organizations must not only plan effectively but also communicate their actions clearly to stakeholders. This puts pressure on various functions and processes to demonstrate how their actions contribute to the organization’s overall performance, aligning purpose, planning, actions, and results in a coherent manner (Micheli & Mari, 2014). However, over-reliance on financial metrics in accounting studies limits the ability to capture the full scope of organizational performance, particularly when it comes to social and environmental dimensions. Conventional methods of measuring economic value often focus solely on financial outcomes, neglecting the broader impacts of organizational activities (Christensen et al., 2021; Gray & Bebbington, 2000; Kolk & Perego, 2010). Similarly, existing disclosure systems remain too dependent on financial transparency, which can obscure the true value created by sustainable practices (Boiral, 2013; Hazelton, 2013; Quattrone, 2022). These gaps stem from the limitations of measurement tools, disclosure structures, and management frameworks, often failing to reflect the long-term impacts of sustainable initiatives on organizational performance (Arjaliès et al., 2023; de Villiers et al., 2024; Perego et al., 2016).

To address these challenges, organizations must adopt a pragmatic approach that extends beyond traditional financial metrics. Performance is inherently relative to a perspective and must account for broader aspects such as the effects of information asymmetry between managers and employees on workplace quality, or the strategic value of an organization’s contributions to social welfare, which can enhance its brand and reputation (Oliveira et al., 2023). Furthermore, external stakeholders, including communities, NGOs, and governments, play a crucial role in shaping decisions related to sustainability and environmental impact mitigation. Institutional pressures also influence corporate participation in social responsibility initiatives (Bebbington & Larrinaga, 2024; Moneva et al., 2006).

Thus, the first step toward achieving sustainable performance is recognizing the broader components of business models that align financial performance with social and environmental dimensions. Organizations must be ‘adaptable to context’ such as regulatory compliance and sustainability standards, while maintaining the flexibility to innovate and adapt to market demands. Efficient resource allocation towards sustainability initiatives depends on solid planning, which aligns practices with strategic objectives, prevents deviations, and optimizes resource use. The level of detail in planning also affects how well an organization can adapt to regulatory, environmental, and social changes. For instance, a study by Oliveira et al. (2023) showed how performance indicators can vary in meaning within different organizational contexts, highlighting the importance of adapting these measures pragmatically to fit specific organizational needs (Oliveira et al., 2023).

Equally important is the need for organizations to ‘focus on priorities’. Flexibility in response to technological advances and market shifts can be achieved by leveraging a combination of control mechanisms rather than relying on rigid, standardized systems (Bellora-Bienengräber et al., 2023). A balanced approach should measure the outcomes of sustainability efforts objectively while recognizing the limitations of standardized performance metrics. However, consistency and clarity in reporting must remain priorities (Adams, 2015; Bellora-Bienengräber et al., 2023; Oliveira et al., 2023).

Defining sustainable performance involves embracing ambiguity and using it as a catalyst for flexibility and innovation. Organizations must balance regulatory requirements with market demands without compromising long-term sustainability objectives. The recurring theme of balance is central to many studies, emphasizing the need to reconcile opposing elements such as flexibility and control (Adler & Chen, 2011). Sustainable performance is not about creating an illusion of clarity but rather understanding the complexities inherent in corporate environments (Diouf & Boiral, 2017; Schaltegger & Burritt, 2018). A key factor for achieving sustainable performance is being ‘structured for compliance’, which ensures consistency and clarity in reporting processes. This structure enables organizations to clearly demonstrate their core mission and commitment to reducing social and environmental impact (Boiral, 2013; Rohendi et al., 2024). By having a strong organizational framework, companies can better align their priorities with long-term values and objectives. Those with a well-defined purpose, centered on sustainable impact, are more likely to effectively integrate environmental, social, and governance dimensions into their strategies, thereby influencing both the pursuit of sustainability goals and their communication to stakeholders (Bebbington & Larrinaga, 2024; Stacchezzini et al., 2016).

Finally, while organizations structure themselves for compliance, they must also remain flexible to adapt to changing realities and critically assess the effectiveness of their integration efforts. Being ‘integrated for effectiveness’ across various areas of the organization is crucial to achieving impactful sustainability results. Operating models should promote collaboration and deliver results efficiently, without rigid adherence to fixed standards (Ahrens & Ferry, 2021; Macve & Chen, 2010; Oliveira et al., 2023). To accurately evaluate sustainable business models, organizational arrangements should be designed with a focus on relativity rather than rigid certainties (Oliveira et al., 2023).

5.2 Sustainable Performance is a Matter of Organizational Arrangements

Sustainable performance depends on a clear set of organizational arrangements, which are systems of coordination and interaction between stakeholders, resources, and internal and external demands (Quattrone, 2022). These arrangements enable the implementation of sustainable practices by aligning the organization’s priorities with the demands of its environment. However, these systems do not operate in isolation; they function within competitive and complex environments, where it is necessary to balance these elements efficiently to maintain a sustainable business model.

The analysis of stratified articles reveals that each cluster (development, innovation, governance, and accountability) displays distinct dynamics in relation to the proposed sustainable business models. Each cluster faces specific challenges that require unique organizational arrangements to address their respective demands. As mentioned earlier, these dynamics are shaped by four key moderating factors: purpose, planning, action, and results (Micheli & Mari, 2014). These factors influence how organizations balance decisions and trade-offs in the priorities of sustainable performance. The moderating factors play a critical role in determining the intensity of decisions, the perception of priorities, and the capacity for organizational response within each cluster. For example, planning aligns sustainable goals with the organization’s strategic objectives, while action ensures the effective execution of these goals. Purpose directs the organization to align its sustainable practices with core values, while results measure the effectiveness of these practices, ensuring their contribution to sustainable performance. These factors also make decisions more responsive to the specific demands and circumstances of each organizational environment, determining how organizations manage their strategic and operational goals in different contexts. The balance between these moderating factors and the dynamics of the clusters is crucial for the successful implementation of sustainable practices.

Table 5 summarizes the challenges and opportunities identified in 30 articles that explore the impact of sustainable development on organizational arrangements related to external demands. These studies highlight challenges such as the fragmentation of global sustainability standards (Alrazi et al., 2015; Kolk & Perego, 2010), difficulties in measuring and reporting social (Hazelton, 2013) and ecological impacts (Journeault et al., 2016; Macve & Chen, 2010), as well as resistance to adopting sustainable practices (Busco et al., 2018). Conversely, the opportunities include the growing demand for sustainability assurance and certifications (Moneva et al., 2023), the strengthening of integrated thinking in environmental accounting practices (Chung & Cho, 2018; Oliver et al., 2016), and the increasing incorporation of circular economy principles into business operations (Aranda-Usón et al., 2020; Scarpellini, 2022).

These studies also emphasize the autonomy of organizations in sustainable development initiatives (Formigoni et al., 2021; Tregidga & Milne, 2022), standardizing institutionalized disclosure practices (Arjaliès et al., 2023; Clarkson et al., 2011), and promoting organizations’ capacity to adapt to future crises (Ahrens & Ferry, 2021; Schaltegger, 2020). The need to respond to new social and environmental pressures and to incorporate internal and external controls (Angotii et al., 2024; Rodrigue & Laine, 2022), as well as to adapt to new regulatory standards (Christofi et al., 2012; Parvez et al., 2019), is also essential. These organizational arrangements are fundamental for managing the complexity of external demands, balancing the flexibility required for sustainable initiatives with the control needed for regulatory, social, and environmental compliance. Based on this, the first research proposition is presented:

Proposition 1: Sustainable performance is directly related to an organization’s ability to balance external demands, including regulatory, social, and environmental pressures.

Table 6 builds on the theoretical analysis of 30 other stratified articles, focusing on accountability in organizational arrangements related to stakeholders. The studies highlight challenges such as the difficulty in standardizing ESG metrics (Arjaliès & Mundy, 2013; Cordazzo et al., 2020), lack of transparency (Caputo et al., 2021; Demir & Min, 2019), and ethical concerns (Parfitt, 2024) in some corporate reports, particularly when influenced by storytelling manipulation (Morrison & Lowe, 2021) and environmental demands (Gray, 2006; Kaur & Lodhia, 2018). Additionally, the relationship between financial, environmental, and social performance can create conflicts (Garcia et al., 2016; Hopper, 2019).

Opportunities for pragmatic improvements in ESG practices are structured around compliance, including the competitive advantage of implementing ESG metrics to better assess socio-environmental performance (Rohendi et al., 2024) and materiality matters, in the sense that companies should identify, prioritize, and disclose information on sustainability issues that are considered material (Jørgensen et al., 2022; Reverte, 2016). There is also tension between maximizing shareholder value and meeting social expectations, as seen in ‘dialogic accounting’, where sustainability reporting and stakeholder engagement create opportunities for stakeholders to express their opinions and influence the content of sustainability reports (Bellucci et al., 2019). Thus, the interdependence of accountability fosters a balance between flexibility in responding to various demands and control over the integrity of reported information. Based on this, the second research proposition is presented:

Proposition 2: Sustainable performance is directly related to meeting the multifaceted demands of stakeholders.

Table 7 presents 38 stratified articles addressing governance, emphasizing its impact on internal demands. Challenges include the lack of global standardization in governance practices (Eccles et al., 2014; Velte & Stawinoga, 2017), the difficulty of monitoring the long-term impact of governance decisions (Burritt & Schaltegger, 2010), and board resistance to adopting greater transparency in reporting practices (Melloni et al., 2017). Information asymmetry between managers and investors is also a source of tension (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2017), especially in companies operating in less regulated markets (Hickman, 2020).

Pragmatic opportunities include improving governance practices through integrated actions for greater effectiveness, with more diverse boards (Ahmed, 2023) and the introduction of non-financial performance metrics (de Villiers et al., 2014; Narayanan & Boyce, 2019). Transparency in voluntary disclosures of environmental (Unerman et al., 2018) and social risks (Lodhia & Hess, 2014) also allows stakeholders’ voices to be incorporated into social value creation (Hall et al., 2015) through “spotlight accounting” (Perkiss et al., 2021). Governance, therefore, plays a critical role in the financial dimension, but its influence is interdependent with the social dimension, as transparency directly impacts stakeholder expectations. Based on this, the following research proposition is presented:

Proposition 3: Sustainable performance is directly related to aligning managers’ interests with transparent and responsible governance practices.

Finally, Table 8, based on 25 additional stratified articles, explores the challenges and opportunities related to innovation and resource allocation. The challenges include the difficulty of measuring the impact of technological innovations on sustainable practices (Barros & Ferreira, 2023) and the lack of incentives for adopting technologies based on a critical dialogical positioning (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019). There are also obstacles related to integrating new technologies without disrupting or undermining these ongoing social commitments (Senn et al., 2022), which may resist change due to high costs (Christensen et al., 2021) or uncertainties about investment returns (Ali et al., 2019; Grewal et al., 2021).

In contrast, the opportunities are linked to the potential of emerging technologies to radically transform how companies operate and measure their environmental impact. The use of big data, AI (de Villiers et al., 2024), and blockchain (Bakarich et al., 2020) can improve the efficiency of sustainable practices (Tiwari & Khan, 2020), as well as facilitate the communication of results to stakeholders (Bebbington & Larrinaga, 2024) through ‘counter-accounting’ (Boiral, 2013). Based on this, the following research proposition is presented:

Proposition 4: Sustainable performance is directly related to the allocation of resources toward technological innovation and sustainable practices.

Sustainable performance is not achieved through simple formulas or static practices – it requires a dynamic balance that evolves with the complexities of modern organizations. In light of the propositions presented here, the path to sustainable performance lies in achieving a flexible and controlled balance, guided either autonomously or collaboratively. This balance recognizes that sustainable purpose, planning, actions, and results do not emerge from a single solution but from a deep understanding of each organization’s challenges and opportunities. By adapting the core building blocks that integrate the economic, social, and environmental dimensions, organizations can navigate these complexities more effectively. Moving forward, multiple practices must be designed, and a multiplicity of perspectives must be recognized and respected when defining what matters. This pragmatic approach aims to ensure that sustainable performance becomes a true source of dialogue and competitive advantage, beyond singular narratives.

5.3 Sustainable Performance is a Matter of Practices

Accounting practices are evolving beyond their traditional role of tracking financial results to become essential tools in guiding organizations through the complexities of sustainable performance. These practices now form the foundation upon which companies build strategies to meet growing institutional demands and stakeholder expectations. In an environment marked by increasing social, environmental, and regulatory pressures, accounting must not only reflect financial realities but also support responsible resource allocation and transparent governance.

In this multifaceted landscape, accounting practices play a dual role. On the one hand, they act as flexible mechanisms, adapting structures and strategies to respond to changing market conditions (Yoshikuni et al., 2024). On the other hand, they serve as control mechanisms, ensuring that decisions and behaviors remain aligned with organizational goals (Lövstål & Jontoft, 2017). This balance enables organizations to swiftly respond to emerging socio-environmental challenges while maintaining long-term standards and objectives. Key tools such as integrated reporting, audits, and budgeting play a critical role in enabling sustainability efforts by providing a clear framework for accountability.

Aligned with the Levers of Control framework (Baird et al., 2019; Bellora-Bienengräber et al., 2023; Beusch et al., 2022; Gond et al., 2012), these practices navigate the delicate balance between adaptability and accountability (Bastini et al., 2022), supporting sustainable governance (de Haan-Hoek et al., 2020), innovation (Barros & Ferreira, 2023), and corporate responsibility (Laguir et al., 2019). Historically, organizations relied on a controlled, unidimensional approach, but new trends are challenging these traditional methods, pushing for more dynamic and inclusive practices.

One of the most significant shifts in accounting today is the emergence of ‘accounts that matter’ – a new form of accounting inspired by “external accounts” (Angotii et al., 2024; Perkiss et al., 2021). These accounts challenge the monolithic narrative of corporate accounting by adopting a multivocal and dialectical perspective. Like external accounts, accounts that matter are created by or on behalf of individuals or groups independent of the organizations being accounted for (Thomson et al., 2015). By providing alternative representations of organizational activities, these accounts bring to light critical social and environmental issues often overlooked in conventional reports (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). By integrating this approach, the review emphasizes the transformative role of accounting in the contemporary context. It is not only a tool for measurement but also a driver of greater transparency and responsible management in corporate sustainable performance. This dialectical perspective highlights the importance of incorporating multiple voices and perspectives in the accounting process (Hall et al., 2015), creating more dynamic spaces that respond to the complexities of social and environmental landscapes (Bellucci et al., 2019; Thomson et al., 2015). Accounts that matter can offer alternative representations of organizational activities (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019), shedding light on critical social and environmental issues, with the goal of challenging and changing harmful practices (Boiral, 2013; Denedo et al., 2017).

In integrating these emerging practices, the review highlights the importance of balancing two critical spectrums: flexibility/control and autonomy/collaboration. To address these challenges, organizations need to strike a balance between flexible adaptation to market demands and the control necessary to ensure alignment with long-term strategic goals. They must balance autonomy – needed for innovation and customized solutions – with collaboration, which ensures that multiple stakeholders have a voice in decision-making and resource allocation. This balance is crucial for effectively managing accounts that matter. In some contexts, high levels of autonomy are necessary to develop innovative initiatives and perform specialized analyses, while in others, collaboration fosters inclusive decision-making, ensuring that diverse perspectives are considered.

The accounting literature has categorized these new practices into several types, including “shadow accounts” (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022), “dialogic accounting” (Bellucci et al., 2019), “spotlight accounting” (Perkiss et al., 2021), “alternative accounts” (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019), and “counter-accounting” (Boiral, 2013; Denedo et al., 2017). Each of these categories offers a distinct approach to capturing sustainable performance, going beyond conventional shareholder-focused reports by incorporating broader social and environmental considerations. The power of these accounts lies in their ability to engage stakeholders by presenting alternative narratives that might otherwise be overlooked or marginalized (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). While traditional accounting practices have been focused primarily on financial performance for shareholders, these new accounts provide data that reflect the broader impact of corporate activities on society and the environment (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019).

By clearly integrating flexibility and control along one axis and autonomy and collaboration along another, organizations can utilize different types of accounts – strategic, relationship, operational, and resource accounts – to create spaces for ongoing reflection and dialogue. These approaches ensure that sustainable performance is not only measured but actively managed. ‘Strategic accounts’ focus on aligning organizational practices with external regulatory standards and public expectations, promoting social inclusivity and trust (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). These accounts bridge the gap between regulatory compliance and societal demands, ensuring that marginalized voices are included in decision-making (Angotii et al., 2024; Journeault et al., 2016). ‘Relationship accounts’ emphasize the importance of dialogic accounting, incorporating diverse perspectives into transparent reports that capture the full spectrum of stakeholder expectations (Bellucci et al., 2019). These accounts challenge dominant corporate narratives and foster trust by ensuring that social and environmental concerns are addressed (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020; Denedo et al., 2017; Hopper, 2019).

‘Operational accounts’ monitor managerial decisions by promoting ongoing dialogue between managers and stakeholders, ensuring that governance frameworks remain flexible and responsive to external pressures (Perkiss et al., 2021). These accounts align corporate governance with broader sustainable performance goals, reinforcing accountability (Cho et al., 2018; Power & Brennan, 2022). ‘Resource accounts’ track resource allocation and project outcomes, encouraging stakeholder participation in the alternative process (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019). These accounts evaluate not only technological advancements but also the social and environmental impacts of innovation, ensuring that community benefits are shared equitably (de Villiers et al., 2024; Tiwari & Khan, 2020).

Ultimately, the balance between these spectrums – flexibility/control and autonomy/collaboration – ensures the effective implementation of accounting practices aimed at sustainability and long-term performance. The typology of accounts that matter moves beyond formal standards, providing greater freedom to incorporate voices from marginalized groups traditionally excluded from dominant accounting narratives (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). These accounts respond directly to the research question, evolving to integrate financial, social, and environmental dimensions, thereby creating alternative representations of corporate performance (Morrison & Lowe, 2021) and communicating new visions that speak to both corporate objectives and the needs of the broader social fabric (Busco et al., 2018).

Although still predominantly conceptual, this typology of accounts holds the potential to democratize accountability by promoting multivocal approaches aimed at fostering systemic change (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022; Thomson et al., 2015). Furthermore, these accounts foster an iterative relationship among the key components of sustainability. For instance, in the innovation cluster, these accounts can be implemented more flexibly by involving community accountants (Perkiss et al., 2021), facilitating participatory monitoring of organizational performance.

Similarly, in the development cluster, these accounts can be enhanced by supporting collective actions and building a robust governance foundation (Arjaliès et al., 2022). In the accountability cluster, these accounts centralize sustainability information in more disruptive, public forums (Perkiss et al., 2021). Finally, in the governance cluster, these accounts allow for comparison, aggregation, and analysis to inform decision-making that favors marginalized or historically silenced groups (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). Thus, these clusters interact iteratively within a continuum that spans traditional accounting practices and contemporary multivocal approaches. Accounts that matter occupy a crucial intermediate space, where accounting practices can be reinterpreted through a pluralistic lens, enabling performative representations of organizational behavior, where accounting practices actively shape and reflect sustainability efforts. This typology supports integrated thinking (Oliver et al., 2016), focusing on development, innovation, accountability, and governance. It offers more accessible and inclusive accounting practices that meet the socio-environmental demands of all stakeholders, promoting a holistic view of business activities (Dillard & Vinnari, 2019).

While this integration represents an aspirational ideal, accounts that matter offer a practical solution to move toward a more inclusive and sustainable performative accounting model, summarized in Table 9. By leveraging alternative data sources and enhancing information accessibility through emerging technologies – such as crowdsourcing accounts (Perkiss et al., 2021) – these accounts reshape how we measure, manage, and disclose organizational performance. This, in turn, creates a performative space where accounting practices can thrive by promoting greater transparency, innovation, and democratic participation, effectively aligning long-term strategic goals with day-to-day operational activities.

6. Discussion and Avenues for Further Research

This section discusses the theoretical structure developed so far, based on a systematic review that raised propositions on how accounting practices can evolve to integrate sustainable dimensions into organizational performance. By reinterpreting these practices through the lens of the accounts that matter, socio-environmental issues previously overlooked have been uncovered, demonstrating how these practices can promote greater transparency and corporate accountability (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). More specifically, we extended the theoretical understanding of these accounts by proposing a framework for integrating sustainability performance into business, based on research findings that examine key components of sustainability, presented in Figure 8.

The discussion focuses on articulating, based on these stratified articles, both the challenges and opportunities that these accounting practices present in facilitating the integration of sustainable dimensions into organizational performance. The key to their effectiveness lies in achieving an iterative balance between flexibility and control, as well as between autonomy and collaboration, mediated by the accounts that matter. This balance suggests that an organization’s ability to adapt its practices to its specific context, while maintaining control over its operations, is fundamental to the success of sustainable integration. Although the propositions raised should be empirically tested to refine and further validate their applicability in diverse organizational contexts, these theoretical insights already offer a valuable starting point. They pave the way for future investigations that may lead to more sustainable and responsible corporate practices. In this sense, the challenge is to recognize that the measurement, management, and disclosure of sustainability are not static processes; they require continuous organizational and institutional efforts to address evolving perspectives, organizational arrangements, and practices. This adaptation does not happen by chance. Numbers alone are not enough to tackle these challenges; a consistent and strategic approach is essential.

6.1 Strategic Accounts Shaping the Development Agenda

Sustainable development is a concept that encompasses the balance between economic growth, social justice, and environmental preservation (Gray, 2006). In this context, the strategic accounts play a crucial role by planning the integration of these principles, highlighting the gaps and weaknesses in corporate development processes. These accounts provide a more critical and comprehensive view of the impacts of organizational and institutional practices. In addition to revealing the negative consequences of certain economic activities, they also challenge the structures that perpetuate environmental degradation and social inequality.

As discussed by Rodrigue and Laine (2022), these accounts are powerful tools that can transform organizational and sectoral practices by directly confronting harmful or unsustainable situations. By bringing to light information that is often underreported or underestimated, such as the environmental and social impacts of certain practices, these accounts play a vital role in promoting sustainable development within organizations. They provide a platform for marginalized communities and groups to be heard, demanding changes in development models that often benefit only a small portion of society.

Furthermore, integrating these accounts into development processes offers a unique opportunity to reshape practices that may seem sustainable at first glance but conceal long-term negative impacts (Rodrigue & Laine, 2022). For instance, in Angotii et al. (2024), the accounts are used to highlight the harmful effects of mining practices, revealing that although companies may meet minimum legal requirements, their operations continue to generate harmful social and environmental externalities. In this case, the accounts not only expose these failures but also suggest more collaborative and participatory ways to restructure development practices, involving different stakeholders in the process of evaluating and correcting such impacts (Angotii et al., 2024).

In addressing sustainable development, the strategic accounts also act as catalysts for social transformation. As noted by Thomson (2015), when operating in arenas of conflict, these accounts are mobilized to expose the negative effects of corporate policies and practices that directly impact public health, human rights, and the environment (Thomson et al., 2015). Therefore, sustainable development cannot be achieved without a critical and inclusive analysis of these dimensions, and the accounts that matter are essential for fostering this discussion.

Moreover, Journeault et al. (2016) emphasize that sustainable development requires companies to implement strategic accounts that translate environmental intentions into concrete actions. In this sense, referred to as ‘eco-controls’, they can be seen as an additional control mechanism, providing external verification of the consistency between companies’ sustainability rhetoric and their actual practices (Journeault et al., 2016). By highlighting inconsistencies or gaps in corporate practices, these accounts can compel organizations to reevaluate and adjust their development strategies, ensuring that the balance between financial, social, and environmental dimensions is truly achieved at the operational level.

The role of strategic accounts in sustainable development is therefore twofold: while exposing the weaknesses and contradictions of stand-alone sustainable development models, they also offer a path to adapt to the context, creating spaces for multi-stakeholder participation and planning more equitable and accountable alternatives. In this way, autonomous and flexible, these accounts not only promote transparency and accountability, but also help shape more sustainable and inclusive development focused on collective well-being, balancing necessary flexibility with effective oversight.

6.2 Relationship Accounts Enhancing Accountability Frameworks

Accountability has been superficially addressed in many studies on relationship accounts, with several works assuming this concept as self-evident without providing a deeper reflection. Only a few selected studies in the cross-analysis of this key component offer theorized notions of accountability or discuss in more detail the purposes through which the relationship accounts contribute to enhancing accountability. Thus, we categorized these studies into two groups – those that, while offering direct theoretical definitions, broadly address how these accounts can promote responsibility, and those that theoretically explore the role of these accounts in contributing to more effective accountability.

In the first group, studies such as Bellucci et al. (2019) provide broad and direct definitions of accountability, explaining how the relationship accounts can be used to pressure organizations to become more responsible. The authors explore how stakeholder engagement and sustainability reports serve as vehicles for dialogical accounting. The study showed that although companies adopt transparency and dialogue practices, most implement only minimal frameworks for the effective participation of stakeholders, which limits the potential for true accountability. Companies use reports to disclose social and environmental impacts, but the actual impact of these practices on accountability remains superficial, without triggering significant structural changes (Bellucci et al., 2019).

Although the approach of the relationship accounts is relevant and has the potential to verify the materiality of sustainability reports and stakeholder accountability, it has been largely overlooked. This results in a critical gap between the most important sustainability issues and what is effectively reported by organizations. Boiral and Heras-Saizarbitoria (2020) support this criticism by analyzing these accounts, specifically certification statements in sustainability reports. They emphasize that these certifications programs often do not reflect a substantial or material assessment of sustainability practices. Instead of addressing real issues and stakeholder concerns, these statements are disconnected from deeper sustainability dynamics. The authors argue that such statements frequently rely on hyperreal rhetoric, using standardized, procedural language that projects an illusion of rigor and transparency while failing to engage with critical sustainability challenges or provide meaningful accountability. Therefore, although sustainability reports and their verifications may create an appearance of accountability, this accountability is often more symbolic than effective, functioning primarily as a tool for organizational legitimacy rather than as a genuine mechanism of responsibility (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2020).

In the second group, we find theorized approaches that delve deeper into how the relationship accounts can contribute to accountability. Hopper (2019) offers a proactive view, suggesting these accounts should go beyond traditional financial responsibility and include support for the SDGs. The author differentiates between accountability as an ex post facto mechanism, focused on market interests, and accountability as a virtue, which is forward-looking and aims to promote social justice, human rights, and sustainability. He highlights the importance of inclusion, responsibility, and the democratization of accounting processes. The author also criticizes the commercialization of academic institutions, which prioritize publications in high-impact journals over socially responsible and meaningful research. There is a moral imperative for academics and professional accountants to engage with broader social and environmental issues, going beyond traditional financial reports to promote dialogue, transparency, and global accountability (Hopper, 2019).

When assessing the role of the accounts that matter, it is essential to understand the necessary balance between flexibility and control. While these accounts provide flexibility for diverse stakeholders, especially those marginalized, to express their concerns and contribute new perspectives, they must also offer robust control. This ensures that corporate practices are effectively monitored and that companies are held accountable for their actions. The real challenge here, therefore, lies in seeking this balance, i.e. creating relationship accounts that allow space for active stakeholder participation and promote innovation, while maintaining rigorous control over social, environmental, and financial impacts, ensuring that the accounts contribute effectively to purpose and transformative accountability. This is exemplified in the Denedo et al. (2017) study on their examination of NGO campaigns on these accounts in the Niger Delta. The campaigns sought to expose governance and accountability system failures in multinational oil companies and promote reforms. However, the NGO representatives expressed skepticism about the effectiveness of merely exposing these gaps. Instead, they recognized the need to form coalitions with powerful actors, such as investors and judicial systems, to provoke real structural changes in governance systems (Denedo et al., 2017).

In this interaction between flexibility and collaboration levels, the structured approach for compliance is fundamental. The relationship accounts offer flexibility by allowing different stakeholders, including those typically marginalized, to express their concerns and contribute alternative views. In addition, they provide a level of interdependent control by ensuring that accountability and governance are rigorously monitored so that companies are held accountable for their impacts. The true challenge for these accounts lies in maintaining this purpose: offering enough flexibility to accommodate multiple perspectives and foster innovation while maintaining robust control to ensure responsibility and transparency across all dimensions of performance.

6.3 Operational Accounts Strengthening Governance Structures

Governance is a fundamental component both in theory and in practice, encompassing a wide range of structures, systems, and processes, making it difficult to define precisely. It involves monitoring, reporting, and decision-making that impact all aspects of an organization. In the selected studies, the operational accounts serve two main potential functions in relation to governance: they can be used to reinforce existing claims or as a tool to reform governance practices.

Regarding existing claims, Cho et al. (2018) provide a clear example of how major oil and gas companies in the US use sustainability discourse to build an image of environmental responsibility, while behind the scenes, their political actions contradict this narrative. The study analyzes these companies’ activities related to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR) Act, which aimed to allow oil exploration in ecologically sensitive areas of the ANWR. While publicly promoting a narrative of environmental responsibility, these companies actively supported the passage of legislation permitting exploration in these protected areas. This contrast between the public image of sustainability and actual political actions reveals the use of sustainability discourse as an impression management tool. Although the authors demonstrated that increasing the perception of transparency and governance through corporate sustainability discourse did not result in significant structural changes, it underscores an important lesson: balancing public discourse and concrete actions is essential (Cho et al., 2018). Effectively integrating financial, social, and environmental dimensions is the only way for sustainability to evolve from mere façade into a genuine and meaningful practice within organizations.

The analysis of this transformation suggests that not all forms of governance have the same impact in terms of change. Some accounts are more effective in promoting transformative actions than others. In this context, the operational accounts play a crucial role in highlighting these differences while exposing the flaws and inadequacies of traditional governance practices. Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al. (2017) highlight sustainability report certifications programs as examples of mechanisms that enhance the credibility and relevance of information by reducing information asymmetries and improving data accuracy. Certifications conducted by qualified professionals, particularly within robust institutional contexts, have the potential to reconfigure governance systems, fostering greater flexibility and facilitating the effective integration of multiple dimensions of sustainable performance (Cuadrado-Ballesteros et al., 2017). Therefore, it becomes essential to investigate how and to what extent these practices are impacted or reconfigured by these accounts, especially in systems that require greater flexibility to integrate multiple dimensions of sustainable performance.