Abstract

Writing this article has allowed me to reflect on the many ups and downs of my career. In this personal reflection I discuss the challenges I encountered, the insights I have gleaned from these experiences, which I hope will be helpful to those embarking on an academic career or those simply wondering about academic life. The ups considerably outweigh the downs. Overall, I have enjoyed a wonderfully fulfilling experience, with so many opportunities leading to a rich, long and interesting professional life. Academic careers involve a lot of rejection, of which I used to be ashamed. Now I view the rejections as empowering, as badges of honour. Rejection is energy![1] I hope readers will benefit from my personal reflections and realise that what might appear from a distance to be a successful career involved (and continues to involve) many unsuccessful episodes.

I commence this article by summarising my career.[2] I then reflect on each aspect: lecturing, research and contribution to my communities. Van der Stede (2018) discusses the challenges of multitasking academics. In juggling these three roles, I adopt a 40:40:20 model in terms of how I allocate my time. I enjoy the variety of the academic year, some periods being research intensive, other periods being teaching intensive. Van der Stede (2018) argues that a balanced portfolio of academic activities has positive spillover effects.

A unique feature of an academic career is the length of time over which it develops, how public it is nowadays, and how research and publication decisions stay with you over your career and beyond. Decisions made and events of decades ago remain influential today. It is only looking back over those decades that I can make some sense of events. I have documented 20 key insights from these reflections, which readers may find useful (summarised in Table 1 further on). My reflections are inevitably retrospective and as such limited. I love (almost) all aspects of my job as an academic, which motivates me.

Author’s Note

I dedicate this article to the person whose initiative, innovation, collegiality and friendship most helped me in my career, Aileen Pierce. Thank you, Aileen, for all you did for me. I will be forever in your debt. Another UCD colleague, Mary Lambkin, deserves a special mention, for giving me an outstanding piece of advice at a key point in my career.

1. My Career Journey

I completed my undergraduate science (microbiology and biochemistry) degree at University College Dublin (UCD). I was not a great student, but in my final year I decided I would try to get a first-class honours degree. I devised a plan to achieve this objective. To the surprise of my lecturers and my classmates, I was awarded a first-class honours degree, the only one in my class of 25 honours microbiology students. This plan characterises my whole career. I am not supersmart. My achievements have much more to do with hard work, persistence and determination than smarts. (Insight ①: Hard work, persistence and determination are more valuable than “smarts”.) At that time, I had no intention of becoming an academic. However, in the academic world, unlike other domains, a first-class honours degree has a coinage, so my plan proved valuable.

Although I loved science, at the time in Ireland I could not see a career in it, and I was determined to have a career. So, I decided to change disciplines. I wanted the change to be substantive, in the form of a professional qualification. Chartered accountancy seemed most appropriate to my skills (particularly attention to detail). Looking back, I had no idea of what I was letting myself in for. I had not studied accounting at school. Had I known how hard it would be, I would not have undertaken it. I found the examinations (which I passed first time), study and working full-time challenging. I completed my science-degree finals in September and the following June I sat the first (of three levels of) professional accountancy examinations. As a graduate, I was exempted the first level of examinations. I only filled in the gaps from that exemption when I was asked to teach first-year accounting in UCD several years later.

I joined Stokes Kennedy Crowley & Co., now KPMG, as an articled clerk. The firm had a policy then of recruiting a quota of “non-relevant” graduates and a quota of female trainees. I satisfied two of the quotas in one person. I am very grateful and proud of my four years with KPMG, a great brand on my CV, a signal of quality. The professionalism and work ethic I learned over those four years have stood to me in the unstructured world of academia. Working in a Big Four firm opens a huge network, not to mention many friends. KPMG alumni events are always enjoyable reminders of those years.

More recently, I was interviewed by two UK accounting professors who are studying the experiences of female professors (Ferguson et al., 2024). They expressed surprise at how much I enjoyed my time in KPMG, saying that other female interviewees did not have such good experiences in Big Four firms. I responded that I believed leaving the company one year after my three-year training contract, with no ambitions to progress within the firm,[3] meant that I was no threat to any other ambitious colleagues, and KPMG was full of highly driven ambitious people.

Following my four years with KPMG, I joined the UCD Department of Accountancy as an assistant lecturer. The expectation that I would complete a PhD was made quite clear from the outset. But when I went to find out how to go about a PhD, I was sent to speak with a professor at another Irish university. He advised me to “go into the library and read”. I did that and six weeks later I came out of the library, extremely frustrated. I had no idea of the purpose of reading. I had no sense of direction.

However, at that time I was heavily involved in the accountancy profession. After I qualified, I became co-ordinator of Financial Information Service Centres (FISC), which offered free financial advice to those who could not afford to pay an accountant. FISC operated under the umbrella of Chartered Accountants Ireland. This assignment involved media appearances, especially during budget time, and was the beginning of obtaining valuable experience working with radio and television.

Following FISC, I was elected to the Committee of the Leinster Society of Chartered Accountants,[4] ultimately becoming Chair. This was at a time when the business press was beginning to realise that there were too few women featuring in business coverage. That year as Chair, nearly every time we held an event, my photograph was in the business pages of the national newspapers.

That high-profile year led to my first non-executive directorship. The Central Bank of Ireland required bancassurance[5] companies to have two independent non-executive directors. I was appointed to the board of Lifetime, Bank of Ireland’s bancassurance subsidiary. Further non-executive director appointments followed. I had no idea at the time how influential these town-and-gown experiences and non-executive director appointments would subsequently be on my academic career. They laid the foundation for one insight I pass on to other academics: You have to get out of your office (Insight ②). I have found the practical experiences from my exposure to the business world to be invaluable in my academic work.

I was at a crossroads at the end of my term on the Leinster Society of Chartered Accountants committee. Would I continue on to the Council of Chartered Accountants Ireland or would I get my act together as an academic? I decided to focus on my academic career.

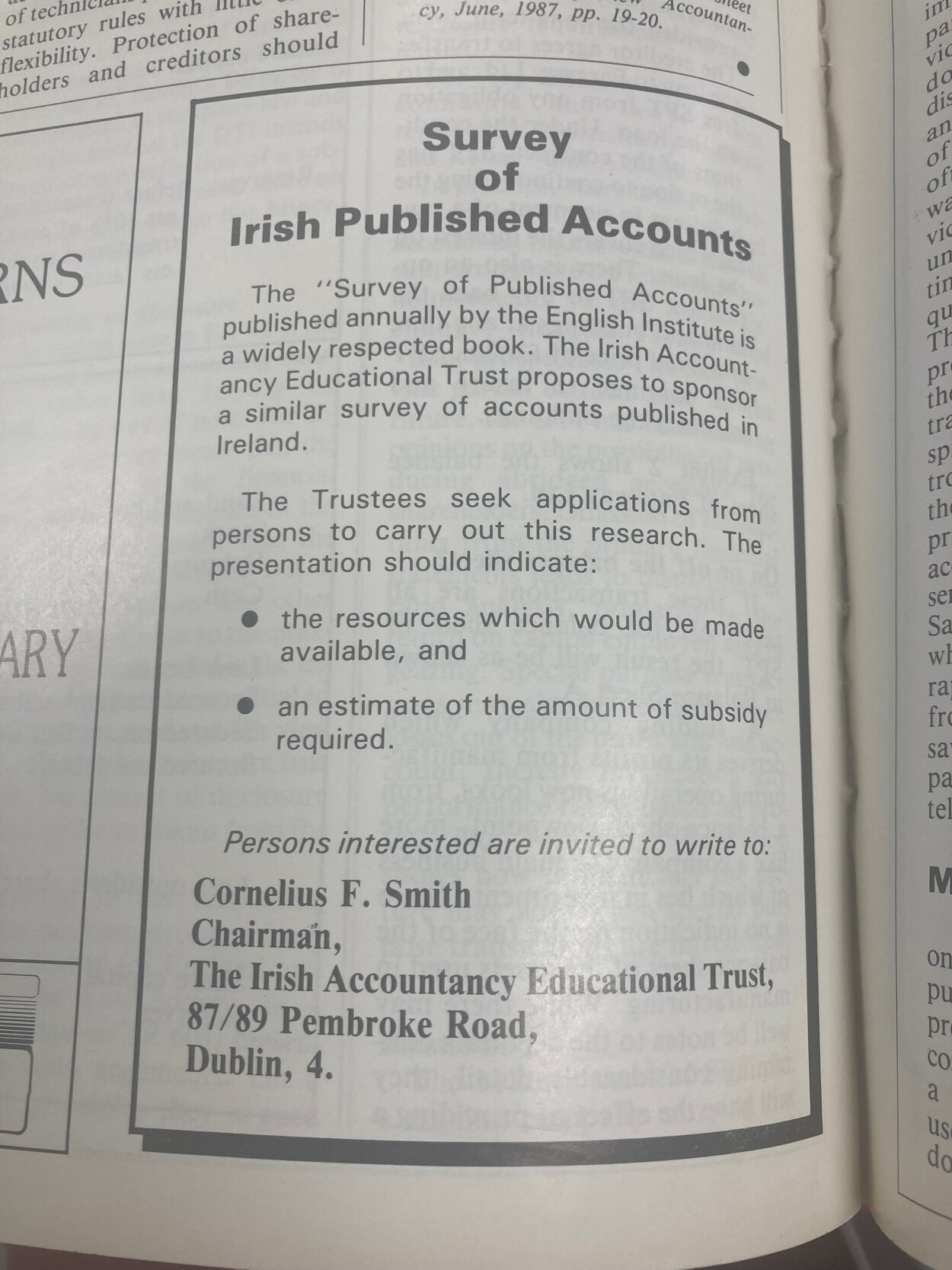

During this time, thanks to Aileen Pierce, I was writing and publishing. Aileen responded to a notice in Accountancy Ireland (the magazine of Chartered Accountants Ireland) looking for members interested in researching Irish published accounts (Figure 1).[6] Aileen’s application was successful, which led to four books and several articles in professional accounting journals. The fourth book was part of a 12-book series, Financial Reporting in Europe, involving the then 12 countries in the European Union. There were several meetings of the team, through which I met the co-author of the UK volume, Professor Sidney J. Gray, probably the most published UK accounting academic at the time.

I asked Professor Gray to supervise my doctorate. That marked the end of what I call my 12 years in the wilderness struggling to get a PhD started. But once I started my doctoral studies, I made an unexpected discovery in my efforts to get the “union card”. I discovered I loved research and I have not looked back since. I consider those three years completing my PhD as one of the happiest periods of my life. Thus, another insight: Research what you enjoy (Insight ③). At the time I was his doctoral student, Sid Gray was at the University of Warwick. Studying outside my own country led to another insight: Write for an international audience (Insight ④). I stopped thinking parochially and factored an international perspective into my work, using unique local and international contexts to address higher-level issues.[7] Reflecting back on my 12 years in the wilderness, I now realise that when I commenced my PhD, I had worked out quite a lot in those years, and consequently I made some wise decisions on commencing and during my doctoral studies.

On my doctoral journey, I also began to appreciate the importance of publishing, at a time when publications were not as valued as they are now.[8] I published every word of my dissertation: three refereed journal articles, two reports published by professional accounting bodies and one book chapter.[9] I continue to actively publish to this day, because I love it. I say to colleagues, if you see me in my office on a Saturday (working on my research), you can be sure I am having a good time.

I now also realise my 12 years in the wilderness was beneficial in terms of working it out by myself. By the end of my doctoral degree, I was capable of independent research. Nowadays, doctoral students receive more support than I did. But I come across some academics with PhDs who, in my opinion, are not capable of independent research. Fox (2018) and Panozzo (1997)[10] capture some of this sentiment.

Following my doctoral studies, I hit a bump in the road. At the time, the experience was extremely painful, so much so that I feel the pain in my viscera to this day. Through three (male) deans and their (male) colleagues, I had difficulty in getting promoted. I had received nine unsolicited letters from the Bursar (my “letters of shame”) (Drujon d’Astros et al., 2024) informing me that I was not eligible for promotion as I did not have a PhD, even though I had not applied for promotion! Then post-PhD, when I applied for promotion, three of the four male candidates promoted ahead of me had no PhDs, let alone any publications.[11] When I applied for the next round of promotions, I was turned down again, two male colleagues being promoted instead.[12] My reaction to being turned down for promotion was to redouble/triple my efforts to prove they had made the wrong choices. This was the start of that rejection-generating energy. I channelled my anger into a productive focus. Looking back on those painful episodes, I realise they had a long-term benefit. Those episodes led to another insight: They cannot take my track record away from me (Insight ⑤: Focus on your track record), which remains with me to this day. This insight gave me great focus and contributed to my productivity as a researcher, leading to another insight: Rejection is energy! (Insight ⑥). This focus on my track record also protects me. Powerful people cannot take my track record away from me. (Insight ⑦: After knockdowns, get up and try again.) Nowadays, academic publication track records are more public (via Google Scholar, Publish-or-Perish, Scopus) than ever before. A track record generates opportunities and invitations (e.g., invitations to visiting positions at other universities (18 so far); seminar presentations, authoring opportunities, etc.). Finally, focussing on my track record gives me a sense of purpose (Edmans, 2022).[13]

Once I finally got my chair, I was free to devote my efforts to the good of UCD, unfettered by threats from powerful people. As it was a chair in management, I moved my research interests towards corporate governance, a more managerial than accounting area. I founded the UCD Centre for Corporate Governance and developed the UCD Diploma in Corporate Governance, the first such executive-education qualification in the university. The launch of this Diploma in Corporate Governance qualification was also the first time in Ireland director training became available. Not only have these initiatives been very valuable financially to UCD, they also established UCD as the go-to place for corporate governance expertise in the country. My motivation in setting up the centre was not financial. Rather, in addition to providing much-needed director training, bringing directors into a university was one way of opening the “black box” (Lawrence, 1997) of the boardroom, which could be valuable for corporate governance research.[14] By the end of my term as Programme Director, 475 people had graduated from the UCD Diploma in Corporate Governance, thereby building a resource for Ireland of graduates with considerable corporate governance expertise. In addition, I consider these 475 people to be friends and love meeting them at business and networking events.

Over my career, I have been very lucky in receiving recognition for my research. Some of these awards[15] have been initiated by female academics. As females have risen to positions of influence, they have the ability to influence the choice of awardees.

2. Lecturing: Our Most Important Role

It is depressing to read authors who have worked in the US confessing to being pressurised to downplay teaching (e.g., Ravenscroft, 2018, p. 25) and how teaching is not valued in promotions (e.g., Edmans, 2022, p. 22), although conversely Shevlin (2018, p. 40) says business schools value high-quality teaching. I always put lecturing first, ahead of research and administrative duties and service roles. When I was completing the last year of my PhD, my body was in front of the class, but my mind was elsewhere. I got slated in the Master of Accounting student evaluations that year. The evaluations were so bad that the head of UCD Accountancy could not face telling me and asked my friend Aileen Pierce to break the bad news to me. I left UCD that day in tears. But I learned a valuable lesson from that unfortunate episode. I never again put my research or anything else ahead of my lecturing. Number one, we have to look after our students. Nothing else comes close in importance. (Insight ⑧: Lecturing is our number one priority.)

I love lecturing. I am proud that I lecture at all levels: undergraduate large classes,[16] postgraduate smaller classes and executive education students. Each level involves different skills. Large undergraduate classes involve trying to keep the students engaged. I find humour to be a powerful pedagogical tool. I also ensure I have authority in the lectures, so the students know who is in charge. Postgraduate classes involve a great deal of dialogue and debate, helping students realise accounting is not black and white, notwithstanding the appearance of precision in balance sheets that balance. In executive education, mature students bring a great deal of knowledge, expertise and experience to the lectures. The job of lecturer is to draw out that resource so it is shared with all the students, in terms of peer-to-peer learning. I ensure the students do as much of the talking as possible during executive-education lectures.

I have lecturing down to a fine art in terms of efficiency. (Insight ⑨: Don’t let lecturing cannibalise research time.) First, I lecture in the same areas as I research with great resonances between the two (consistent with Van der Stede’s (2018) positive spillover effects mentioned at the start of this paper). The following quotation captures some of the spillover effects: “If you want to master something, teach it. The more you teach, the better you learn. Teaching is a powerful tool to learning.”[17] To be a good lecturer, you have to be an expert in the material, which requires a forensic depth of knowledge. I have been delivering the same modules for many years, thereby cutting down on new-module preparation. I write all my own module materials, as I cannot deliver other people’s textbook materials. While time consuming at the start, that initial effort reaps rewards over subsequent years.

I do a lot of lecturing, much more than my fair share. I try to be a good citizen. (Insight ⑩: Be a good citizen.) Being well over my annual lecturing load protects me. For example, no one questions my visiting professorships to universities in Australia, Canada, New Zealand (generally during the summer months), as I have delivered so much lecturing during the teaching semesters.

My objective as a lecturer is for students to discover that accounting is a lot more interesting than they might have expected at the start of the module. (Insight ⑪: Make accounting interesting.) In a world of dumbing down and grade inflation in academia, I make sure my modules are as challenging today as they were decades ago. In my MSc (Business and Executive Coaching) (see Section 4.1), I learned about “unconditional positive regard” (Rogers, 1957, p. 96). I realised that I instinctively adopt this perspective with my students, especially with the weaker students struggling with accounting. (Insight ⑫: Treat students with unconditional positive regard.) It grates with me if I hear colleagues complaining about their students, although I am sure on occasion I have similarly offended. I try to be of service to my students. I operate an open-door policy (not restricted office hours), encouraging my students to consult me if I am in my office. I love these unscheduled drop-in sessions and experience satisfaction from helping students. I am consistently present in UCD, so students see me around and can consult me, or just “shoot the breeze” with me, if they wish. I also promise my students a 24-hour response to emails, usually responding much more quickly. If the query is too complex to answer by email, I will phone the student and talk them through the issue. Again, it is a good feeling to give students a good service.

My town-and-gown career supports me in bringing a real-world flavour into my lectures. These practical experiences give me credibility in the classroom. In my undergraduate lectures, I still use anecdotes from my days as an auditor in KPMG. The non-executive director roles are also invaluable sources of practical business insights in lectures. I am especially motivated to take on governance roles (many pro bono) because of their value when lecturing at executive-education level. Without practical experience, it is difficult to lecture mature students who return to education with a considerable amount of practical experience themselves. In addition to using anecdotes, I start all my undergraduate and postgraduate lectures with a “News-of-the-Week” slot, to which the students are the contributors. I have two objectives: first, to get students to read the business press; second, to give my modules a real-world relevance.

I operate a principle with all my classes of no surprises. I try in various ways to develop trust with my students. (Insight ⑬: Develop trust with students.) One of my key performance indicators (KPIs) is no complaints from students after examinations, because the examinations are exactly as I describe (only in outline) to the students. I make all my examination solutions, together with the marking schemes, available to students. Thus, students have the opportunity to prepare well for the examinations. I build trust and openness with students, for example, providing them with detailed feedback on their performance after examination results are posted, leading to another KPI, no students appeal their examination outcomes.

2.1 Postgraduate Supervision

The UCD Master of Business Administration (MBA) and UCD Master of Accounting (MAcc) students used to have to complete a minor dissertation over the summer. We had to supervise 1–2 MBA dissertations and 10–12 MAcc dissertations each year. I learned a huge amount from those supervisions, and even published from some of those minor dissertations.[18] The arrangement I had with the students (who after completing their dissertations had left UCD and were working full-time) was that they would provide me with their Microsoft Word files, and I would write the papers from the dissertations and take the papers through the double-/triple-blind review process to publication. This arrangement benefited both me and the students. For the students, the experience revealed the arduous process of getting published in refereed journals.

An especially rewarding but quite risky[19] teaching is with doctoral students. At a doctoral level, the relationship between student and lecturer is turned on its head, as my colleague Donncha Kavanagh (2013) beautifully captured in remarks he made at a commencement address at a UCD conferring:

What we find in this model [of learning] is that the lecturer takes on the servant role [rather than the sage-on-the-stage role], with the student, in effect, having responsibility for setting a unique, just-for-you curriculum, defining their own particular research agenda, and mapping out their own journey of inquiry.

I am highly motivated to take on doctoral students as I do not want any doctoral students to have the experiences I had trying to get my own PhD started. I especially enjoy supporting students in their doctoral journeys. I am very hands-on as a doctoral supervisor, working hard to give students as much support as possible, consistent with training independent researchers. (Insight ⑭: Provide hands-on support to doctoral students.) I want my doctoral students to enjoy the experience as much as I did. I have supervised 11 doctoral students during my career. The doctoral relationship lasts a long time, well beyond the supervision period, and includes post-PhD publications and continuing collaboration. Academics are very privileged to have jobs that can make a difference to people. This is especially so at doctoral level. The relationship develops into a friendship and lasts a lifetime.

3. Research

I completed a large sample quantitative study for my PhD. My research question came from the four books mentioned earlier – why do companies disclose information voluntarily? My dissertation, Disclosure of Profit Forecasts during Takeover Bids, involved 701 takeover bids and applied statistical analysis to analyse the data. The study yielded 250 profit forecasts.[20] Then came a turning point: I wondered what was in the 250 profit forecasts. That content analysis of the 250 profit forecasts marked my switching from being a quantitative to a qualitative researcher. Quantitative and qualitative approaches address different research questions. The mixed methods I used provided richer insights than would a quantitative study on its own.

My primary research interests are financial reporting (voluntary disclosure, impression management and rhetoric and argument) and corporate governance (boards of directors, audit committees, whistleblowing). As such, I play to my strengths as a chartered accountant lecturing on financial reporting and from my experiences as a non-executive director. I find it frustrating to read academic papers where the authors do not appear to know or understand the area they are researching, such that they pursue naïve approaches because of their lack of practical experience. In a third area of research, arising from a time when I thought my academic career was in trouble, in an effort to re-engineer my career, I co-authored a book on forensic accounting.

I have tried to find research projects and topics that pass the “dinner party test”: If you told someone at a dinner party about your research, would they respond, “That’s interesting”? For example, I think the takeover bid setting, especially hostile takeovers, made my doctoral topic interesting.

Another research turning point was accepting an invitation from a Department of Industry and Commerce civil servant who wanted an Irish academic to attend the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) International Symposium, Measuring and Reporting Intellectual Capital, in Amsterdam. I wrote a paper in six weeks, knowing little about intellectual capital beforehand. Another conference attendee was James Guthrie, Joint Editor of Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal (AAAJ). That chance meeting with James on a canal boat in Amsterdam led to becoming part of the AAAJ community (Carnegie & Napier, 2017), which introduced a supportive and welcoming like-minded group of international scholars into my network. I brought back a suitcase of materials from that groundbreaking OECD conference, which led to another paper with a UCD Master of Accounting student. These two papers on intellectual capital are among my top four most-cited papers, all because I said “yes”. They also demonstrate the advantage of working in a fledgling area of research (but avoid fad-du-jour topics). Subsequent papers tend to cite those early papers. This episode also reflects my tendency to be opportunistic. If an opportunity comes my way, my instinct is to take the opportunity. I said “yes” to the Department’s invitation. (Insight ⑮: Say “yes” to opportunities.)

Another research turning point was supervising Doris Merkl-Davies’s doctoral dissertation. Doris’s primary degree is in linguistics. Her expertise helped us to contribute to accounting research by bringing ideas from linguistics into financial reporting. Our first paper, my most highly cited paper, commenced a stream of research which established our expertise and reputation in impression management in financial reporting adapted from the work of sociologist Erving Goffman (1959).

There is no shame in rejection. Some academics have even published their “CVs of failure”, to reveal the rejections behind apparent success. My papers have been rejected 72 times (and counting!).[21] Rejections are hard. However, I have always held the view that my work is not good. So when reviewers conclude similarly, my reaction is – just tell me what to do to fix the problems. Thus, I can take the negative feedback. I used to be ashamed of being rejected. Now I view these rejections as badges of honour. No matter how often they knock me down, I get up and try again. (Insight ⑦: After knockdowns, get up and try again. See also Insight ⑥: Rejection is energy!)

I have various visual images of myself in my head: a skittle; a dog with a bone. I see myself as like a bowling skittle. No matter how many times I get knocked down, I will bounce back up again. I am like a dog with a bone – I will not let go. The grit credentials of determination, doggedness and persistence arguably are more valuable than IQ. They translate into energy to meet the challenge of rejection. The drive and motivation to keep bouncing back relates to the experience of being rejected for promotion in UCD, which I described in Section 1. That rejection had a huge effect on me, which I cannot shake off to this day. I need to prove them wrong for promoting all those males without PhDs and publications ahead of me.

Now I relish the challenge of trying to get published in good quality journals. All papers are publishable. Some of my rejected papers have even ended up in better quality journals than the journals that had rejected my work. It is often down to the luck of the referee draw (Edmans, 2022, p. 4). In a recent paper, the two reviewers rejecting the paper were quite harsh. The reviewers in the better quality journal were more sympathetic, helpful and constructive (see Figure 2). We authors were confident that we had a novel research contribution, but it is up to authors to sell their work.[22] We sold the idea better in our second attempt to get published. Some excellent advice on rejections is available from journal editors (e.g., Edmans, 2023; Stolowy, 2017).

3.1 Co-authors

The academic life in some respects is a solitary one. We prepare our lecture materials on our own, we research on our own. Co-authors introduce a welcome social aspect to academic life. Co-authors can help with productivity – two heads are better than one.[23] Co-authors can share the pain of rejection. On the other hand, co-authors can hinder productivity. This can happen if there is not a meeting of minds/chemistry between authors and if the co-authors’ work practices do not gel. (Insight ⑯: Co-author, while being careful in choosing your co-authors.) Tucker et al. (2016) discuss the pros and cons of co-authorship, based on interviews with 76 accounting academics.

Over the years, I am lucky to have had exceptional co-authors. So far, I have co-authored with 50 people, ranging from UCD masters students, doctoral students, executive education students, UCD colleagues and colleagues outside UCD. One of my first co-authors was Aileen Pierce. Aileen and I engaged in what we called the “red-pen job”, critiquing each other’s work, annotating comments on each other’s text with a red pen. Aileen was exceptionally good at this exercise. I learned a huge amount from her, especially how to write clearly. Because Aileen is my friend, I could accept her critique. Having a critical friend is invaluable for providing feedback on work, especially before papers go out for the double-/triple-blind review process in international refereed journals.[24] Another wonderful co-author is Doris Merkl-Davies. Doris is not a chartered accountant. As mentioned earlier, her expertise is linguistics, her primary degree. Doris imports ideas from linguistics into financial reporting, which makes our research novel. Having co-authors with complementary skills is another reason for multiple-authored papers. Sean Bradley Power’s expertise in Python, a programming language for text analysis, allows us to analyse large data, comprising our huge British South Africa Company dataset (discussed further on).

I do not co-author with people who do not share the same values as I do. Unfortunately, predatory co-authors roam the field, often more senior academics preying on less experienced academics. Hyper-productive authors make me nervous, ones with strangely large numbers of publications in a short period of time. Multiple-author publication cartels are increasingly evident, as are citation cartels/rings. Multiple-author publication cartels are where people come together and offer each other reciprocal honorary authorship to increase each other’s publications, what de Mesnard (2017, p. 779) calls a “publication club”. Citation cartels/rings are where authors or journal editors team up to increase the citations of their articles/journals by disproportionately citing articles of cartel members more than other relevant articles (Enago Academy, 2022). These people are to be avoided. My advice is to work with people, get to know them, before jumping into a relationship from which it may be difficult to exit.

I avoid co-authors who are predators. I do not work with free riders. I never take a free ride as co-author. I work hard to ensure trust with co-authors. For example, if my co-authors have the original idea for the research, their names come first even if not in alphabetical order.

In the commercial world (such as Big Four accountancy practices), people are encouraged to leave at a relatively young age (55/60). It is a joy that my younger colleagues want to work with me. Some are the same age as my sons. There are few work environments where there is so much regard between senior and junior staff, another privilege of the academic life.

3.2 Conferences

I have a rule for myself – I never attend a conference unless I am presenting a paper,[25] otherwise for me it is academic tourism, but there may be circumstances where it is justified. Apart from presenting and getting feedback on papers, conference attendance is essential for networking, meeting other scholars, potentially meeting a co-author,[26] and meeting journal editors, associate editors and reviewers. Meeting and knowing these key influencers will not get your paper published. But it might reduce the chance of a paper being desk rejected if they could put a face to a name.[27] I attended one conference solely motivated by the objective of meeting editors and editorial board members of a journal so that when I submitted the paper I had presented at the conference, the editor might recognise it and send it out for review rather than desk rejecting it. When attending conferences, I try to catch up with everyone already in my network. I also like expanding my network at conferences by speaking with strangers. You never know what such random conversations can lead to (such as my meeting with James Guthrie mentioned earlier).

3.3 Principles Underlying My Approach to Research

In this section, I document some of my approaches to research, which I hope readers will find useful. This approach works for me. It might not work for others. However, what is important is to have a plan.

3.3.1 Targets

I have (private) annual targets for myself, guiding my productivity. I find it motivates me to have quantified targets, such as the number of refereed journal articles to publish a year in journals of a specified quality. To meet these targets, I have to manage my pipeline carefully. I document my research projects in the form of a pipeline, using my CV for that purpose, identifying projects from start to finish, in terms of stages of completion. Having projects at various stages in the pipeline is ideal. My pipeline has 10 stages. There are “skull and crossbones” at Stage 1, starting a new project. It is easy and exciting to start new projects. It is very hard to get them out at the other end, published in good quality international refereed journals. I focus my efforts on the later stages of my pipeline. For example, I put refereed journal revise-and-resubmit recommendations to the top of my to-do list.[28] Getting published takes a long time, often many years. I try not to add to the time by sitting on revise-and-resubmits.

Many years ago, I heard Lee Parker (Joint Editor of AAAJ) delivering a seminar to doctoral students. One of his comments yielded another insight: The Dean’s KPIs are not your KPIs (Insight ⑰). Had I followed the Deans’ KPIs,[29] I would have ruined my career (as they ruined some colleagues’ careers). While being mindful of academic performance systems, academics have to judiciously devise their own KPIs, especially around research, that will lead to an enjoyable and hopefully successful career.

3.3.2 Say ‘Yes’

My instinct is to always say “yes” (Insight ⑮ earlier). You never know what benefits will come from saying “yes”. The only exception to this principle is when I think someone is trying to use me, to make a doormat of me. Unfortunately, there are some people like that in the academic world, but I have been lucky to generally avoid them. Thus, have the judgement to know when to say “no”.

3.3.3 Sacrifice Perfection for Productivity

I try to make my work as perfect as possible. Top academics do not make spelling mistakes, punctuation errors, are not sloppy with referencing, etc. I try to persuade the refereed journal reviewers to think my work is written by a top academic. The tiny details/the hygiene issues matter. I am obsessive in my attention to detail. However, conversely, I work fast, sacrificing perfection for productivity. I make lots of mistakes, but I no longer beat myself up for so doing. I write quickly (“quick and dirty”), refining and editing my work multiple times (“prinking and preening”). (Insight ⑱: Sacrifice perfection for productivity.)

3.3.4 Reputation

In Section 3.1, I touched upon some unethical practices concerning co-authors. I am careful about my reputation. (Insight ⑲: Mind your reputation.) For example, I do not publish in journals about which I have heard stories of unacceptable practices. Unfortunately, the pressure university managers put academics under has led to academics experiencing anxiety (Coulthard & Keller, 2016) and an erosion of standards in academic publishing (Harley et al., 2014). I have personally experienced or come across in the double-/triple-blind review process the following unethical practices: order of authors’ names not alphabetical, not agreed with the co-authors; citation “amnesia” – plagiarism of other authors’ material without acknowledgement; self-plagiarism – authors not citing their earlier work; slicing and dicing (“salami slicing”) data too thinly; guest authorship – authors named on a paper who have not input into the research; ghost authorship – authors not named on a paper who have input into the research; fabrication of data; small changes in wording to avoid being detected by journal anti-plagiarism software; citation stacking – getting authors/editors to cite papers to increase the paper’s/journal’s citations; lack of transparency – key data not disclosed that makes the research look better than it is; mis-citation to hide weakness in the research.[30] I also avoid predatory publishers and predatory journals which claim to be legitimate but are not. Over my career, I have received many unsolicited emails from publishers and journals I have never heard of.[31] These are warnings to be extremely careful to observe high standards in research.

4. Contributing to the University, Business and Wider Society

Service in a university context involves service to one’s university division (in my case, UCD Accountancy and the UCD College of Business), to the university, externally to one’s academic community and externally to the business community. I try to be a good citizen by contributing to these communities. (Insight ⑩: Be a good citizen.)[32] I have approached my work in UCD by being a role model: do as I do, not as I say.[33]

I also contribute to my academic community. I am/was associate editor of three journals (The British Accounting Review, AAAJ, and Accounting Forum). In addition, I do a considerable amount of reviewing for refereed journals (over 600 reviews to date). I always say “yes” (Insight ⑮) to requests to review papers, with one exception. I do not review for predatory journals. Reviewing is an excellent self-development tool. You can learn from other people’s mistakes. Reviewing can also build reputation with key influencers such as journal editors and associate editors.

In terms of service to the business community, in Ireland academics have a contract which allows us to spend 20% of our time (“Devlin time” – Devlin, 1970) on work external to the university. Over my career, I have had extensive external engagement, in the public sector (generally pro bono) and in the private sector (often pro bono). In addition to my non-executive directorships and audit committee roles, I have held roles in professional bodies (my own, Chartered Accountants Ireland; the Society of Actuaries in Ireland where I chaired its disciplinary arm for 10 years). I have also participated in government assignments (Vice-chair of the Review Group on Auditing; Chair of the Commission on Financial Management and Control Systems in the Health Services; Chair of the Expert Advisory Committee on the Independent Review of the Governance and Culture of RTÉ[34]). These external roles are invaluable to my work in UCD. My practical experience enhances my domain expertise and brings great credibility in lectures. It also feeds into my research, where I combine my academic expertise and practitioner experience.

4.1 Mentoring

In 2021, I completed an MSc (Business and Executive Coaching) at the UCD Michael Smurfit Graduate School of Business. After a science degree, chartered accountancy and a PhD in Accounting, I felt it was time to get in touch with my “soft” side (which has proved elusive!). Completing this degree has been useful in the mentoring I do, trying to help my early/mid-career colleagues. Tough and all as I found it at the beginning of my career, it is much tougher nowadays for my early career colleagues. At the very least, we should be kind and generous to those coming after us. (Insight ⑳: Be supportive and encouraging to colleagues.) I am amazed at how badly some senior academics treat other (earlier career) academics, having been at the receiving end of some toxic behaviour myself and having witnessed it at conferences and seminars. Universities and academic bodies[35] are increasingly aware of the need to help younger academics learn the rules of the game. Many more opportunities to obtain help are consequently available to early/mid-career colleagues than in my day. But early career colleagues need to search out the assistance that is available. There is no use waiting in your office expecting colleagues to take the initiative.

I summarise my insights from earlier sections in Table 1.

5. Epilogue

The academic life is privileged. Academics enjoy a lot of autonomy, choosing what to research and teach and who to work with. I have benefited from the positive energy generated from great colleagues and supportive networks. I have been employed at UCD for over 44 years. I plan to continue my lecturing and research endeavours for the benefit of UCD as a research-active and teaching-active retired member of staff. I love UCD. I am proud of UCD’s achievements, and my role as a member of the UCD team in contributing to its success.

Notwithstanding my lengthy service at UCD, the job feels as fresh today as when I started. Lecturing is entertaining, with no class the same as a previous class. Having to keep up to date with the latest developments also keeps me on my toes. To get published in international refereed journals, each paper has to make a unique substantive contribution. Thus, the topics for research have to be novel, constantly requiring new ideas leading to exciting new projects and papers. My current research with Sean Bradley Power, on his project on the British South Africa Company (the company Cecil Rhodes used to colonise Rhodesia, modern-day Zimbabwe), is one of the most interesting research projects of my career. We have five papers published out of our huge dataset and are currently working on several new papers. Another project I am proud of is with doctoral student Helen Pernelet. Thanks to Helen, we are only the second team of researchers to get access to the “black box” of the boardroom to video- and audio-record board meetings. We believe our insights from this level of access have been ground-breaking.

At this stage in my career, I feel I am “in the zone” (Gallwey, 2000, p. 44) and am loving it more than I ever have. I feel privileged to have such an enjoyable and fulfilling career and to work with so many outstanding people. I love being busy. I have a low threshold of boredom. With my lecturing and research, I rarely spend a boring day. I hope my reflections on a long career, with many highs and lows along the way, will be of interest and more importantly some use to current and future academics.

I learned the importance of the influence of systemic contexts on people during my recent MSc (Business and Executive Coaching). I have been extremely lucky. My own systemics have been exceptional. I have a loving husband, three wonderful sons, now three fabulous daughters-in-law, and two gorgeous young grandchildren. Although I dedicate this essay to Aileen Pierce, in closing, I also acknowledge my husband’s extraordinary support, and the fun times I have had with my sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren, who ensure that I have some work-life balance! 😊

Acknowledgements

I thank the Accounting, Finance, & Governance Review editors for inviting me to write this article, and two reviewers for their valuable comments. I thank Oonagh Breen, Donncha Kavanagh, John McCallig, Emma McDaid, Eimear McKeown, Seán O’Reilly, Sean Bradley Power and Andrea Prothero for feedback on the paper.

I thank Edward F. Crawford, US Ambassador to Ireland 2019–2021, for this phrase.

Haynes (2006) discusses the biographical turn in social science research, including autobiography, observing that (at that time) it was rarely used. Since then, there have been several examples of accounting academics using autobiographical insights on an accounting academic career (e.g., Callahan, 2018; Chapman et al., 2024; Ravenscroft, 2018; Shevlin, 2018; Stone, 2018; Stout, 2016, 2018a), on publishing (Stout, 2018b), on accounting research (e.g., Hermanson, 2018).

I first met Aileen Pierce on her last day in KPMG. She was a year ahead of me in the firm because UCD’s commerce degree took three years, whereas a UCD science degree took four years. Aileen told me she was leaving KPMG to take up a lecturing position in (as it was then) the Regional Technical College, Athlone. A year later, Aileen joined UCD. That one chance conversation led to my joining UCD the year after Aileen.

The Leinster Society of Chartered Accountants is the largest of Chartered Accountants Ireland’s district societies.

Bancassurance refers to a bank and an insurance company operating in tandem.

The Irish Accountancy Educational Trust (1988). Survey of Irish Published Accounts, Accountancy Ireland, July, p. 34.

I regret in my early work including “Irish”/“Ireland” in the title of my papers. Now, I focus on the issue of interest, not the country in which the research was conducted.

The following quotation captures one perspective on the importance of academics publishing: “When we are asked why we require faculty members who are primarily teachers to publish in order to gain promotion or tenure, we answer that if they do not do research, they will not remain intellectually alive. Their teaching will not keep up with the progress of their disciplines. It is not the research products that we value, but their engagement with research which guarantees their attention to the literature – to the new knowledge being produced elsewhere.” (Simon, 1992, p. 130).

Sid Gray suggested it would be better for my career to sole author my two main publications from my PhD. This was generous of him and displayed his very high ethical standards.

Fabrizio Panozzo and I attended the same European Accounting Association Doctoral Colloquium in Venice and the American Accounting Association Doctoral Colloquium at Lake Tahoe of which he writes.

In advance of the promotions’ meeting, the then Dean asked the Head of UCD Accountancy: “Have you not made your strategic alliances?” When my colleague told me of the conversation, I had a horrible sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach that promotions would be based on “strategic alliances” and not merit.

With all the policies on equality, diversity and inclusion nowadays, you might assume that what happened to me could not happen now. Sadly, nothing could be further from the truth. I see younger colleagues being treated badly and I see outright discrimination by those in positions of power. Colson et al. (2024) confirm this.

Edmans (2022, p. 5) cites a (then) Wharton colleague, Andew Metrick, who defines the purpose of a professor as “the creation and dissemination of knowledge”. Edmans (2022, p. 6) also cites Laurie Hodrick (2011) who describes being a professor as a “way of life”. This resonates. I never stop thinking about how I could improve my lectures. I am constantly thinking about new ideas for papers. This “way of life” is hugely enjoyable and stimulating.

I co-authored one paper with an executive-education student, John Redmond, former Company Secretary of one of Ireland’s largest commercial semi-state bodies, the Electricity Supply Board (ESB).

Some of these are documented on my UCD profile page: https://people.ucd.ie/niamh.brennan.

I teach Financial Accounting 2 to a class of approximately 500 students. Consequently, almost all undergraduates in the UCD College of Business have me as a lecturer. I see this as an opportunity to profile myself amongst the students, who go on to become leaders in business. Thus, having lectured so many students over the years, at almost every event I attend, I have the privilege and pleasure of meeting former students.

These words are commonly attributed to the American theoretical physicist Richard Feynman.

Five papers with MBA students; six papers with MAcc students.

Risky in that the relationship is one-on-one, and not all doctoral students stay the course.

Demonstrating the long-lasting nature of influences on an academic’s career mentioned at the start of this paper, I continue to research profit forecasts. For example, during COVID-19, I co-authored a paper on COVID-19 profit warnings (negative profit forecasts).

All academics experience rejection. The most famous paper in accounting, by Ball and Brown (1968), was first rejected by The Accounting Review before it was published in the Journal of Accounting Research (Ball & Brown, 2014, p. 17).

Sangster (2024) describes a paper being rejected by four reviewers/two accounting journals. He had to go outside accounting to get his paper accepted by a Chartered Association of Business Schools 4-ranked journal. He is scathing in his critique of two of the accounting journal reviews, calling the reviews incompetent and ignorant.

In one rejection, the paper had been rejected by three reviewers of a C journal. I was absolutely convinced there was a really original idea in the paper. I invited Collette Kirwan to join us as a co-author to help us lift the paper. She did a brilliant job, finding the work of the Japanese academic Nonaka (1994) on knowledge creation to theorise the research. The paper was published in an A journal.

Edmans (2022) describes the value of collegiate people giving and receiving feedback on papers.

Or as Lee Parker (Joint Editor of AAAJ) says, a paper is a passport to get into a conference.

The exceptional writing partnership between Brendan O’Dwyer and the late Jeffrey Unerman commenced when they met at a conference and discovered common interests.

With an Irish name like Niamh, the key influencers know I am female if they have met me at a conference and might even be able to pronounce my name!

Shevlin’s (2018, p. 36) description of his work practices resonates with me: always having a to-do list and the week’s planned activities. When my sons were small, I used to type a two-week diary of activities (theirs and mine!) to try to keep home life and work life on track, which I stuck to my computer. Quite a juggling act!

Examples of the Dean’s KPIs include pressure to lecture overseas; pressure to publish in journals of a specified ranking.

I reviewed a paper in which I found four breaches of the Committee on Publishing Ethics (COPE) standards: (i) lack of transparency concerning non-disclosure of the date of administering the survey instrument, which was administered 20 years earlier; (ii) self-plagiarism, in not citing two earlier (very old) publications based on the same research; (iii) slicing and dicing the data too thinly, across five papers (two of which were not cited); (iv) small changes in wording compared with earlier papers, which made me wonder were the author(s) using online article-rewriter tools whose purpose is to avoid being detected by anti-plagiarism software. The editor rejected the paper in the normal fashion, which I consider to be an inappropriately mild response to highly unethical behaviour.

“We would like to solicit your gracious presence as a speaker at the upcoming 2nd International Conference…” (from an advertising and marketing conference); “In recognition of your outstanding reputation and contribution in your field, we would like to nominate you as a possible Editorial Board Member (EBM) for the journal”; “We are glad to invite you to submit any type of article for our prestigious journal….Your contribution is of great importance for us and it will help the journal to establish its high standards” (from a physiotherapy journal).

Edmans (2022, p. 11) says that a purposeful professor is intrinsically motivated to serve and is not just motivated by the reputational benefit of service to the professor.

Fleischman et al. (2024) use the term “servant leadership” to describe good citizenship.

Ireland’s national broadcaster.

For example, the British Accounting & Finance Association has introduced a mentoring scheme (see https://bafa.ac.uk/bafa-mentoring/), which offers research career development for early career researchers. The European Accounting Association has a PhD mentoring initiative (https://eaa-online.org/arc/events/submit-to-the-eaa-phd-mentoring-initiative-pmi-4/) to help European PhD students refine their research proposals. This is a commendable initiative, but I would not call it “mentoring”.