1. Introduction

The board of directors is considered an important corporate governance mechanism that aligns the interests of shareholders with those of managers. The effectiveness of a board in performing its fiduciary duties critically depends on various factors, including its independence. The literature suggests that board independence is a dominant factor that significantly affects the board’s capacity to supervise and counsel managers (Black & Kim, 2012; Y. Liu et al., 2015). Independent directors are considered to be independent, and, therefore, the degree of a board’s independence is traditionally assessed by the proportion of independent directors on the board.

However, this measure of board independence has received criticism within the existing literature on corporate governance and finance. Carl Icahn is quoted as saying “members of the boards are cronies appointed by the very CEOs they’re supposed to be watching.” Moreover, Coles et al. (2014, p. 1751) argue that the proportion of independent directors as a measure of independence is weak because “many directors are co-opted, and the board is captured.” Similarly, Finkelstein and Hambrick (1989) assert that CEOs can gain control over the board by strategically selecting new directors who rarely disagree with their decisions. Additionally, a lack of significant variation in the degree of board independence over time suggests that the proportion of external directors, as a proxy for board independence, may often fail to capture the dynamics of publicly traded firms. For instance, according to the Spencer Stuart Board Index (2021), the average proportion of independent directors in US firms changed by only 2% in the last ten years (from 84% in 2011 to 86% in 2021). Similarly, the average tenure of independent directors declined marginally from 8.7 years in 2011 to 7.7 years in 2021. As a result, the concept of ‘board co-option’ has recently garnered considerable attention from academics and practitioners. It is believed that co-opted directors can better explain board behaviour and the impartiality of members than traditional measures (Coles et al., 2014). Coles et al. (2014, p. 1753) further argue that “if there were a statistical horse race between co-option and independence, co-option would appear to be more successful.” Co-opted directors are those appointed after a CEO assumes office (Coles et al., 2014).

Directors are generally appointed by shareholders at the annual general meeting (AGM), where shareholders or their authorised representatives vote to elect the directors. The newly elected directors then appoint candidates for key positions such as board chair, CEO, and others. However, directors are often appointed between AGMs to fill vacancies caused by resignations, retirements, or other forms of attrition. In such cases, companies adopt bylaws that authorise the incumbent board to elect directors to fill vacancies, indicating that board co-option is the process of adding directors between AGMs. The new director typically serves until the next AGM, at which shareholders choose either to reappoint co-opted directors or to end their tenure.

One striking difference between a regular board and a co-opted board is that the former is appointed by shareholders at the AGM, who, in turn, appoint the CEO. In such a scenario, the board of directors (BoD) is an exogenous body, and the CEO ostensibly has no influence over the appointment of the board. In the latter case, when the existing board nominates and appoints new directors between two AGMs, the CEO, occupying the top executive position in the firm, often plays a crucial role in shaping the board and influencing director appointments. Coles et al. (2014) argue that those directors appointed after the new CEO takes office are more likely to support the decisions of the new CEO, regardless of their independent or non-independent status. This has significant repercussions for corporate governance and performance.

The literature shows diverse opinions regarding the effect of board co-option on firm performance. One stream of thought argues that the board of directors, acting on behalf of shareholders, often pressures CEOs to focus on boosting financial performance, which, in turn, tempts CEOs to maximise short-term performance at the expense of long-term sustainability. For instance, managers may avoid investing in long-term value-enhancing projects, such as research and development (R&D), because such projects are risky, and failures in these areas could damage their reputation and career prospects. Therefore, motivating managers to invest in R&D requires necessary incentives for long-term success and a degree of risk tolerance (Ederer & Manso, 2013). Co-opted members can provide such mechanisms by insulating managers from short-term performance pressures and helping them focus on maximising the firm’s wealth. Chen et al. (2019) show that co-opted directors protect CEOs by reducing the likelihood of dismissal. Similarly, Coles et al. (2014) show that pay-performance sensitivity is lower in firms with a higher proportion of co-opted members on the board. This finding can be interpreted as an innovation-motivating incentive contract between boards and managers (Nguyen et al., 2021).

A contrasting strand of literature argues that co-opted boards exacerbate agency conflicts and fail to protect shareholders’ interests from managerial expropriation because co-opted directors are often selected from the same network as the CEO (Coles et al., 2014) and share similar beliefs, vision, and work ethics (Wintoki & Xi, 2020). As a result, they tend to be more loyal to the CEO than non-co-opted members. Studies document that co-opted boards are positively associated with higher managerial pay (Coles et al., 2014), earnings management (Harris & Erkan, 2021), and corporate misconduct (Zaman et al., 2021). Furthermore, co-opted boards reduce analysts’ attention towards firms (Papangkorn et al., 2020), lower management accountability (W. M. Lim et al., 2022), decrease firms’ clawback provisions (S. Huang et al., 2019), increase stock volatility (Baghdadi et al., 2020), and raise the cost of capital (Adams & Ferreira, 2009). Additionally, firms with a higher proportion of co-opted members receive less favourable recommendations from analysts than those with a lower percentage of co-opted members (Papangkorn et al., 2020). Jiraporn and Lee (2018) demonstrate a positive association between board co-option and excess cash holdings by firms, which increases the likelihood of overinvestment (Iskandar-Datta & Jia, 2014) and corruption (Thakur & Kannadhasan, 2019).

Despite substantial research conducted over the past two decades on board co-option focusing on the above arguments, no study has attempted to conduct a narrative review of the subject. It is essential to explore board co-option research, reflecting on past achievements and identifying avenues for future research. In line with these considerations, this paper aims to explore the current research evidence on board co-option, clarify key concepts and factors related to co-option, and identify knowledge gaps in existing research. We follow Munn et al. (2018) in justifying the selection of a scoping review as a research method.

Our review makes several contributions to the literature. First, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to conduct a systematic scoping review of board co-option research. The practice of board co-option has been increasing in the US since 1996 (Coles et al., 2014), and the topic has received considerable attention since Coles et al. (2014) systematically analysed the effect of board co-option on various firms’ and managerial attributes. This review thus offers a comprehensive and in-depth analysis of the research produced over the last two decades on board co-option practices. It collates and synthesises a wide array of studies, providing structured insights into the evolving dynamics and theoretical frameworks within the governance field.

Second, the existing literature presents both negative and positive effects of co-opted directors on multiple attributes of firms. Our scoping review charts the main themes and patterns that have defined research on board co-option between 2000 and 2020. The review organises studies into thematic categories, such as the influence of co-option on firm performance, risk, board decision-making, board diversity, and firm reporting quality. This categorisation illustrates how scholarly attention has shifted over time and identifies areas that have not been thoroughly investigated. Early-career researchers and practitioners can gain deeper insights into past studies’ findings on board co-option and explore relatively underexplored areas that require more attention. Furthermore, our critical review of past findings identifies gaps and suggests future directions for board co-option research. It is thus hoped that our scoping review will raise awareness of the importance of considering board co-option in future corporate governance research.

Third, our scoping review summarises the consequences of board co-option on corporate governance, highlighting its dual function as a means of bringing new perspectives to the boardroom and as a tactic that current board members may use to solidify their power and hinder significant changes. This detailed analysis is expected to have important policy implications, providing a better understanding of the negative and positive effects of board co-option.

2. Theory Underlying Board Co-option Practices

A brief review of theory underlying board co-option is useful to set the context of the remainder of the paper. Most studies analyse the effect of board co-option on firms through the lens of the traditional principal-agent relationship. Agency theory posits that modern firms are owned by atomistic shareholders who are scattered and independent and cannot participate in the day-to-day activities of the firm. As a result, they hire skilled managers as agents, granting them significant control over operations. This separation between ownership and control allows managers considerable freedom in establishing their own personal empires, often to the detriment of shareholders (Fama & Jensen, 1983). Consequently, owners have commonly implemented various strategies to mitigate the resulting agency issues. One such technique involves appointing a board of directors to oversee managers. However, a board’s effectiveness in monitoring management critically depends on its independence. Outside directors are considered independent, as they are more likely to remain outside the CEO’s control compared with their inside or executive counterparts.

Given the likelihood that CEOs influence the appointment of co-opted directors, the literature suggests that co-opted boards exacerbate agency conflicts within firms. Based on this theoretical premise, studies have sought to assess the effects of co-opted directors on various firm dynamics. For instance, it is argued that director co-option negatively impacts market share growth in firms with higher cash holdings, as managers with more co-opted directors have fewer incentives to make optimal decisions, leading to less efficient cash allocation (Harris & Nguyen, 2022). Firms with more co-opted directors may be less efficient in managing working capital, resulting in higher cash conversion cycles. However, this could also intensify the propensity for working capital, thereby reducing the cash cycle and strengthening the firm’s liquidity position (Harris & Hampton, 2022).

Further studies have shown that the presence of co-opted directors, whether executive or independent, weakens the board’s ability to monitor top management. Williamson (2008) argues that it is the incompetence of the board that excessively empowers the CEO. Similarly, Cohen et al. (2010) report that CEOs may favour incompetent ‘cheerleaders’ on the board to face less resistance from directors. Song and Thakor (2006) demonstrate that CEOs tend to select incompetent directors more frequently during times of economic stability than during downturns. Such findings complement Bebchuk and Fried’s (2005) research on CEOs’ involvement in the nomination process, who often maintain social relationships with the directors. In such situations, directors who satisfy the legal requirement of independence may not serve their role on the board independently. Elms and Kent (2023) indicate that powerful CEOs are reluctant to adopt a nomination committee, reducing transparency in the director appointment process (Raleigh & De Bruijne, 2017).

Coles et al. (2014) report that weak monitoring is proportional to the number of co-opted directors on a board. Increased connectedness between directors and managers creates more opportunities for managers to pursue personal goals, such as shirking and personal empire-building (Morse et al., 2011), engaging in improper corporate practices leading to misconduct (Beasley, 1996), and hiding or delaying the detection of key information (Khanna et al., 2015). Additionally, an empowered CEO in an environment lacking proper monitoring can lead to costly investment decisions, including investment in self-serving projects (Jensen, 1986), overinvestment (Rajkovic, 2020), and subsidising poorly performing projects (Berger & Hann, 2003). These incidents are costly for firms and can result in lacklustre performance.

A few studies, however, adopt stakeholder theory (El Saleh, 2023; Kyaw et al., 2021; Maneenop et al., 2024) or stakeholder-agency theory (Zaman et al., 2021), suggesting that balancing stakeholders’ interests with a firm’s economic interests improves management’s discretion. However, when multiple stakeholders are involved, management may become unaccountable, leading to agency issues. Stakeholder-agency theory suggests that managers have a nexus of contracts with stakeholders, making strategic decisions and allocating resources in line with other stakeholder claims. Firm governance structures oversee these stakeholder-agent relationships.

Cassell et al. (2018) explain the role of CEOs in appointing directors through the lens of managerial hegemony theory. The director selection process is significant, as it involves identifying, screening, approving, nominating, and electing directors. CEOs can influence the process by nominating fewer independent directors and more grey directors and using subtle political tactics (Cassell et al., 2018). Despite regulatory changes to limit the influence of insiders, CEOs can still influence director selection. Managerial hegemony theorists argue that governing boards are tools used by professional managers to support and validate their decisions. They believe that professional managers run modern corporations, making all strategic decisions, and that the board of directors serves as a superficial figurehead. Shareholders elect board members, but some names are pre-selected by the professional manager, creating a “managerial capture” effect. The connotative meaning of corporate governance refers to an arrangement where boards play a supportive or subservient role to the professional manager.

3. Method

There is a growing trend towards conducting systematic literature reviews in governance research (Gjaltema et al., 2020; H. Liu et al., 2022). A systematic review allows researchers to refine their data collection process by adopting specific inclusion criteria, resulting in a comprehensive synthesis of existing evidence. However, Drucker et al. (2016) identify several limitations in the systematic review method. First, an inadequate literature search process and poorly defined inclusion/exclusion criteria could lead to sample selection bias. Second, the systematic review process may also suffer from competing interests.

A scoping review offers a range of advantages over a systematic review. It is particularly useful for identifying knowledge gaps, clarifying concepts, and investigating research conducted within a specific field (Munn et al., 2018). A scoping review is ideal for determining the scope or coverage of a body of literature on a particular topic. Following the recommendations of Munn et al. (2018), we considered whether a systematic or scoping review would be more appropriate for this study. Munn et al. (2018) suggest that a systematic review is suitable if the study objective is to (i) explore global evidence, (ii) examine variations in study findings, (iii) contribute to policy decisions, and (iv) identify areas for future research.

Conversely, studies aiming to (i) identify certain characteristics or concepts in past research and map them, (ii) report or discuss these characteristics or concepts, and (iii) identify existing knowledge gaps may benefit from adopting a scoping review. Scoping reviews can provide valuable insights into the state of knowledge in a particular field and help researchers identify areas for future investigation. By conducting a scoping review, researchers can gain a better understanding of the existing literature and formulate research questions that address significant gaps in knowledge. Thus, we find that a scoping review is more appropriate for exploring the research objectives set out in the introduction.

Following Akbarialiabad et al. (2021), we adopt a scoping review method in this study. We employ the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) approach in our scoping review process (McGowan et al., 2020). The PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) ensures rigour and a minimum level of analysis in the scoping review process. The PRISMA-ScR review process is designed to be comprehensive. This scoping review, conducted in accordance with PRISMA-ScR, provides a structured summary of the research, including background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions. We perform the scoping review in five steps, as follows: (i) identify keywords by reviewing past research on co-option, (ii) collect data from Scopus, (iii) apply inclusion and exclusion criteria following PRISMA-ScR recommendations, (iv) extract and synthesise data, and (v) review the final sample. We used a wide range of search terms to cover the available literature on board co-option comprehensively in a formal search.

Following Zhang et al. (2021), we adopt a three-stage literature review approach to identify keywords and collect relevant academic articles for the review process. In the first stage, we searched for the terms “co-option”, “co-opted”, “board co-option”, “CEO co-option”, “CFO co-option”, and “director co-option” in the titles, abstracts, and keywords of academic articles in the Scopus database. Scopus has been widely used for systematic reviews of governance (Gao et al., 2021). The initial search identified 384 documents on co-option. In the second stage, we applied a filtering mechanism to identify documents relevant to our current study. We set two filtering criteria, namely, (i) document type and (ii) subject area. We included only articles in accounting, finance, economics, business, and social sciences. We then examined the titles, keywords, and abstracts of each record to determine their relevance to the review. This two-stage data screening process produced a sample of 84 articles published on board co-option.

In the final stage, we applied two inclusion criteria to ensure the quality of the research publications reviewed in this study. We considered only articles published in journals indexed by both the Chartered Association of Business Schools (CABS) and the Australian Business Deans Council (ABDC) lists, following Rajeevet et al. (2017). Additionally, we considered articles that had received at least one citation. However, we made an exception to the citation criterion for two articles on co-option published in 2023, considering the journal impact factor while including them in the review process (Ramspek et al., 2021). This exception was necessary to ensure that all recent studies on board co-option were included in our review process. Our final sample consists of 30 articles published on board co-option, and a full list is shown in Table 1.

4. Key Themes of Co-option Research

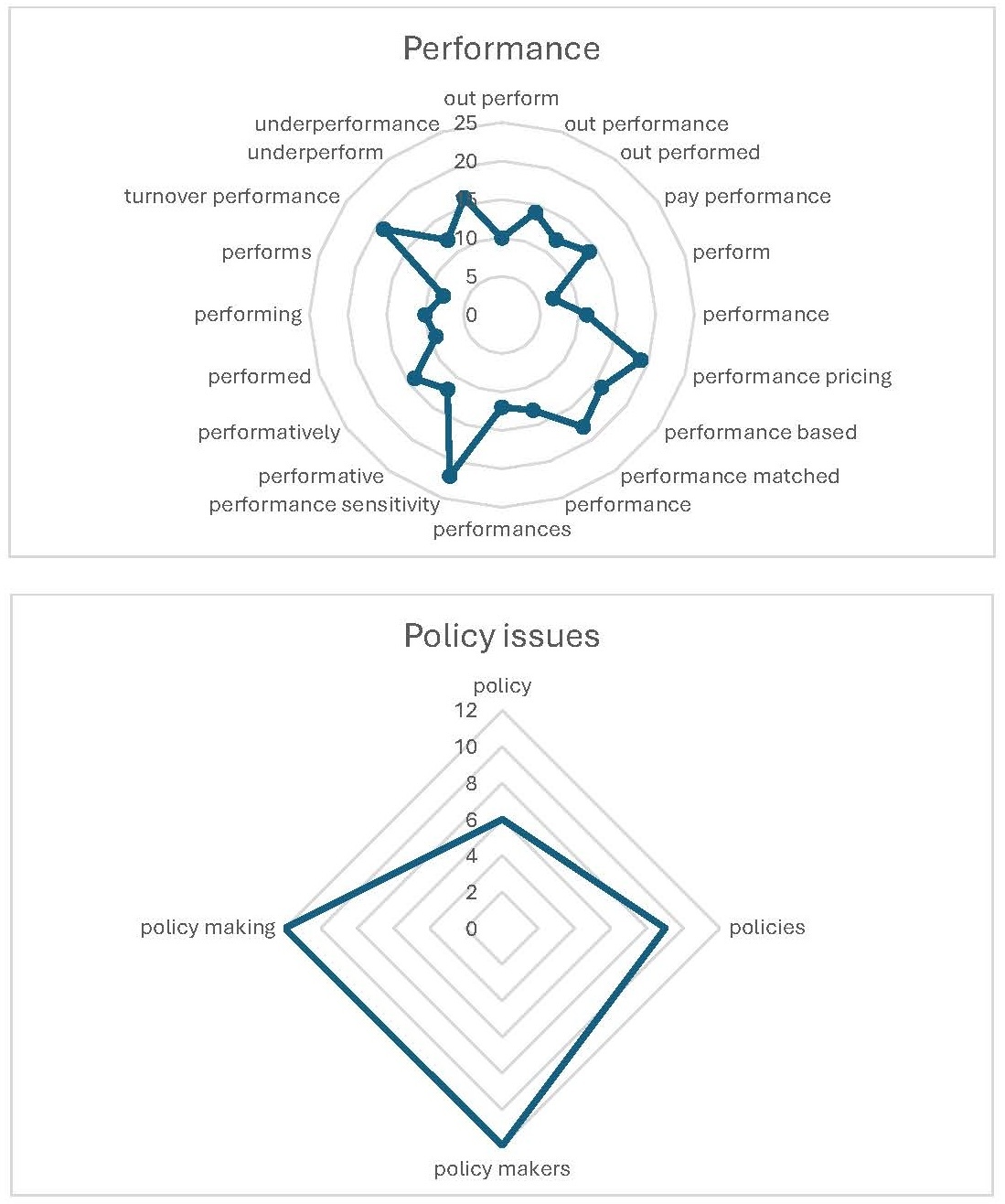

We conducted a thematic content analysis using ATLAS.ti to gain deeper insights into the key areas explored in previous research on board co-option. To carry out the thematic content analysis, we imported all 30 eligible articles into ATLAS.ti. We then ran a word frequency analysis on all 30 articles using the tools available in ATLAS.ti. Following this, we performed a concept analysis to identify the most commonly occurring concepts. We manually mapped the frequently appearing keywords to their relevant concepts to determine the most prevalent themes in board co-option research. Through this thematic content analysis process, we identified the following key themes in board co-option research, namely, (i) performance, (ii) risk, (iii) policy decisions, and (iv) reporting quality – see Figure 1 for a visual depiction of the results. The four themes are now elaborated.

Theme 1: Board Co-option and Firm Performance

Chintrakarn et al. (2016) present evidence that co-opted boards significantly reduce the likelihood of executive removal, thereby increasing the probability of long-term investments. This suggests that co-opted directors can counteract managerial short-termism. Lim et al. (2020) examine the effectiveness of co-opted board members in monitoring the board of directors, finding that a higher proportion of co-opted directors leads to firms facing more stringent covenants. The study also identifies a critical threshold for board co-option, concluding that boards with non-co-opted members benefit from stronger internal monitoring, which helps mitigate covenant violations among unrated borrowers and revolving loans. These findings align with those of Bakar et al. (2020), who observe that board independence correlates with less restrictive covenants, implying that lenders are more willing to delegate monitoring responsibilities to firms with independent boards.

However, the benefits of co-option highlighted by Chintrakarn et al. (2016) and Lim et al. (2020) may not necessarily be reflected in market performance. For instance, Harris and Nguyen (2022) investigate the impact of director co-option on product market performance, considering the board’s advisory role in shaping the firm’s strategic direction and facilitating strategy development and implementation. Drawing on agency theory, the study hypothesises that co-opted directors are more likely to align with managers, thereby increasing agency costs. Harris and Nguyen (2022) confirm that product market performance deteriorates as the CEO co-opts more board members.

Papangkorn et al. (2020) demonstrated that co-opted directors exert a significant negative influence on analyst recommendations. Rahman et al. (2021) revealed that companies with a higher proportion of co-opted directors tend to display increased levels of insider trading profitability, a trend particularly pronounced in firms lacking external monitoring by institutional investors. Rahman et al. (2021) further illustrate that organisations with highly co-opted boards are less inclined to impose insider trading restrictions, leading to greater insider trading profitability. Drawing on evidence from superannuation funds, Yang et al. (2023) conclude that co-opted boards limit fund members’ benefits due to lower performance and higher fees. These findings have broader implications for future governance studies, advocating for closer scrutiny of board co-option in addition to the widely accepted measure of governance quality, namely, board independence.

Theme 2: Board Co-option and Corporate Risk

Baghdadi et al. (2020) examine the impact of board independence (using co-option as a proxy) on corporate default risk and report a significant positive relationship. The study further explores how this positive relationship between co-option and default risk arises from poorer quality and erratic decision-making, which leads to increased performance volatility and diminished consistency in decision-making processes. E. Lee et al. (2021) contribute to the ongoing debate regarding the role of co-opted boards in corporate risk, suggesting that co-opted directors weaken board monitoring, thereby allowing managers to assume more risk.

Huang et al. (2021) provide additional evidence by empirically investigating the influence of co-opted directors on corporate risk-taking behaviour and estimating the moderating effect of social capital. Their study reveals that a higher degree of board co-option results in greater stock return volatility, implying that managers are more likely to behave opportunistically when affiliated directors permit unqualified attitudes. Huang et al. (2021) further showed that board co-option is a stronger predictor of corporate risk-taking behaviour than board independence, suggesting that co-option should be regarded as a general measure of board effectiveness. Bhuiyan et al. (2022) find an inverse relationship between the proportion of co-opted directors on Australian firms’ boards and the cost of equity capital.

Lartey et al. (2021) explore the relationship between board co-option and capital structure decisions, as well as the monitoring effectiveness of non-co-opted and co-opted independent directors on such decisions. Ghafoor et al. (2023) demonstrate that firms with a higher proportion of co-opted directors face increased climate risk. Harris et al. (2019) disclose that board co-option exacerbates product market threats, suggesting that co-opted directors might impair a firm’s competitive position and potentially harm its value. Kao et al. (2020) suggest that co-opted directors elevate crash risk, as they tend to prioritise CEOs’ interests.

Chaivisuttangkun and Jiraporn (2021) contribute to the growing body of governance literature by examining the role of co-opted directors in firm risk during the 2008 financial crisis. They demonstrate that firms with more co-opted directors exhibit significantly lower risk during times of crisis. Yang et al. (2023) show that non-co-opted independent directors are strongly associated with improved firm performance.

Harris and Hampton (2022) conclude that director co-option mitigates managers’ career concerns and innovation risk, motivating them to make better long-term strategic choices and investment decisions. By reducing market pressure to deliver short-term performance, board co-option lessens myopic and short-term behaviour. Additionally, trust between directors and managers is likely to increase with co-option, leading to more board advice on the tactical development and implementation of projects, corporate policies, and strategies. Huang et al. (2019) find that board co-option is negatively associated with the likelihood of clawback adoption, supporting the idea that co-opted directors are unlikely to enforce clawback provisions against the CEO who appointed them.

Theme 3: Board Co-option and Corporate Policy Decisions

Previous studies have explored the impact of CEO characteristics and board composition on corporate policy decisions, including those related to corporate social responsibility practices (Rao & Tilt, 2016), gender diversity (Brammer et al., 2007), compensation (Cook et al., 2019), diversity (Mahadeo et al., 2012), and tax avoidance (Alkurdi, 2020). However, there has been limited research on the role of co-opted boards in corporate policy decisions.

O’Higgins (2002) confirms that the appointment of non-executive directors is primarily driven by the “old boys’ network” and indicates a positive correlation between participants’ perceptions of the “ideal” non-executive director and their self-image. This suggests high self-esteem and satisfaction with their roles as non-executive directors. Coles et al. (2014) show that co-option reduces the effectiveness of board monitoring. Furthermore, Coles et al. (2014) reveal that independent directors who have been co-opted do not behave independently.

Campa et al. (2022) provide empirical evidence on the association between co-opted CFOs and firms’ tax avoidance, showing that CFOs under the dominant influence of the CEO pursue riskier and less socially oriented tax strategies. Auriol and Platteau (2017) explore the trade-off between the level of progressive reforms and political stability in an autocratic regime with heterogeneous income-ideology preferences. Kyaw et al. (2021) find robust evidence that co-opted boards adopt LGBT-supportive policies more frequently than non-co-opted boards. The adoption of such policies is associated with a higher increase in total compensation for management, aligning with Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn’s (2017) findings.

Jiraporn and Lee (2018) suggest that co-opted directors are less effective in monitoring management (Coles et al., 2014). Nishikawa et al. (2022) confirm Jiraporn and Lee’s (2018) findings and contradict Kyaw et al.’s (2021) by providing empirical evidence that a board with a high proportion of co-opted directors is negatively associated with employee welfare. These results indicate that having a high proportion of co-opted directors on the board negatively affects the welfare of employees, who are key stakeholders in the firm.

S. M. Lee et al. (2021) examine the relationship between co-opted boards and the adoption of anti-takeover provisions (ATPs) and conclude that co-opted boards tend to result in less ATP adoption, providing support for the governance substitution hypothesis. S. M. Lee et al.’s (2021) results also align with Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn’s (2017) prior findings, indicating that co-opted boards function as a substitute for CEO power.

Theme 4: Board Co-option and Reporting Quality

Cassell et al. (2018) investigate the impact of audit committee co-option on the quality of monitoring and find that higher levels of audit committee co-option are associated with a greater likelihood of financial misstatements and larger absolute discretionary accruals. These results suggest that the negative effects of audit committee co-option on financial reporting quality are mitigated when the audit committee chair possesses accounting expertise.

Harris and Erkan (2021) conclude that co-option can alleviate managerial myopia with respect to earnings management by shielding top management’s career concerns from employment risk. Specifically, as the risk associated with job security diminishes due to increased co-option, managers tend to exercise less control over earnings as they become less sensitive to meeting earnings expectations.

5. Research Gaps

Based on our analysis, we have identified and reported several gaps in the existing literature on board co-option, which we have grouped into four categories.

First, there is a wide range of firm performance and risk proxies used in previous studies on board co-option, leading to mixed findings. Most research focuses on the impact of board co-option on firm risk and performance, but the coverage is extensive, addressing issues such as dividend policy, default risk, monitoring effectiveness, short- and long-term focus, and capital structure decisions. Consequently, the findings are mixed, limiting the generalisability of the impact of board co-option. For instance, much of the research indicates that a co-opted board leads to weaker dividend payouts (Jiraporn & Lee, 2018), higher corporate misconduct (Cassell et al., 2018), and decreased market share (S. Huang et al., 2019). Conversely, Papangkorn et al. (2020) show that co-opted directors receive more favourable recommendations from analysts.

The second research gap concerns endogeneity issues, which are a significant concern in governance studies. Endogeneity arises from three sources: (i) omitted variable bias, (ii) measurement error, and (iii) reverse causality. Our review reveals that reverse causality is the most common cause of endogeneity bias affecting ordinary least squares (OLS) results in board co-option studies. To address reverse causality, past researchers have predominantly used the difference-in-differences technique (Baghdadi et al., 2020; Coles et al., 2014; Harris & Nguyen, 2022; S. Huang et al., 2019; Jiraporn & Lee, 2018; E. Lee et al., 2021; J. Lim et al., 2020; Rahman et al., 2021). Additionally, the lagged model (Chintrakarn et al., 2016; Yang et al., 2023), two-step GMM technique (Kao et al., 2020; Lartey et al., 2021), and propensity score matching techniques (Bhuiyan et al., 2022) have been used to address reverse causality. We found heterogeneity in how endogeneity issues have been addressed, resulting in varied impacts of board co-option on risk and performance measures for non-financial corporations. Of the 30 studies reviewed, 17 have addressed endogeneity issues.

The third research gap concerns the greater explanatory power of co-option compared with board independence. We have identified that when board co-option variables are introduced into empirical models, the impact of traditional governance measures (specifically board independence) often becomes insignificant. Yang et al. (2023) noted this limitation in their study, attributing it to a small sample size. However, this issue persists even with larger samples; Withisuphakorn and Jiraporn (2017) show that board co-option, as a stronger measure of board effectiveness, has greater explanatory power than board independence for determining corporate outcomes such as CEO turnover, executive pay, and pay-performance sensitivities. These findings support earlier propositions by Coles et al. (2014) and Dikolli et al. (2021) that not all independent directors are effective monitors, with those appointed before the CEO’s appointment having greater explanatory power. Our scoping review highlights that governance studies have yet to fully acknowledge the superior explanatory power of board co-option and continue to use board independence as a measure of board effectiveness.

The final research gap relates to the geographical coverage of board co-option studies. Seventy percent of the studies included in our review examine board co-option in firms operating in the US, with limited evidence from other economies. For example, Williams et al. (2012) is the only study discussing co-option in the UK context. After 10 years, Campa et al. (2022) examined the impact of board co-option on tax avoidance using a European sample. We also reviewed evidence from Australian firms (Bhuiyan et al., 2022; Yang et al., 2023). However, Kao et al. (2020) is the sole study examining co-option in Chinese firms. Thus, there is limited evidence on the impact of board co-option from emerging economies, particularly firms operating in Asia and the Middle East and North Africa.

6. Future Research Directions

Based on our scoping review, we propose several directions for future research on board co-option. Past studies have investigated the impact of board co-option on both systematic and idiosyncratic risk. While S. M. Lee et al. (2021) provide evidence that co-option reduces systematic risk more than idiosyncratic risk, particularly during crises, future research using non-US samples could enhance the generalisability of these findings. Additionally, there appears to be a gap in studies examining board co-option in financial firms.

The attributes of CEOs, such as their education, age, race, and gender, may influence their decision to appoint co-opted members. Therefore, it would be valuable to explore how these dynamics affect CEOs’ selection of co-opted directors. Furthermore, board co-option research has yet to consider the relationship between CEO investment in firm-specific human capital and co-option practices.

Co-option practices may vary across different cultures and countries, and future research could investigate the similarities and differences in co-option practices and their impact on board effectiveness. As most past studies focus on US firms, there is limited understanding of how board co-option and its governance controls affect firm performance in countries with diverse cultural and political structures. Future research may also explore the role of board co-option in other corporate policies and examine its relationship with corporate financial decisions on a cross-country basis.

The ethical attributes of co-opted members may mitigate the negative effects reported in existing literature. Future research could investigate the ethical dimensions of co-option and its potential to perpetuate existing power imbalances within the boardroom. Additionally, the role of co-option in board succession planning warrants examination. Co-option could be strategically employed to ensure a smooth succession process. Research could explore the impact of co-option on board continuity and stability, as well as the factors influencing the decision to co-opt directors as part of succession planning.

7. Conclusion

Our study provides a review of past board co-option research to advance the literature on corporate governance. We undertook this study with two primary objectives: to gain insights into the theoretical and practical significance of co-opted boards and to raise awareness among academics and practitioners about board co-option practices. Our review indicates that co-option, as a measure of board independence, has gained popularity among scholars and policymakers. Most studies rely on agency theory to analyse the effects of co-opted directors on firms, emphasising the monitoring role of directors. However, the director’s advisory role, which could be ideally explained by the resource-based view, remains largely unexplored in the existing literature. While mainstream corporate governance literature explores the dual role of the board of directors, co-option literature primarily focuses on the monitoring role. Hence, further study is needed to observe whether there is a convergence or divergence between traditional and new measures of board independence.

Our analysis also reveals that most studies indicate a value-reducing effect of co-opted boards on firms. Although there is limited literature showing a positive effect of co-opted directors on firms, a few studies demonstrate that co-opted directors insulate managers from short-term performance pressures, leading to increased investment in research and development. These findings highlight the need for careful consideration of co-option in future corporate governance studies. In particular, it is essential to investigate whether the benefits derived from increased investment in research and development outweigh the agency costs associated with board co-option.

Our scoping review has several key theoretical and practical implications. First, we categorise past board co-option studies into four clusters and provide a critical discussion on each cluster. This discussion has practical implications for early-career researchers and practitioners interested in exploring optimal board composition. Second, our review outlines the direction for future corporate governance research by emphasising the importance of considering board co-option as a critical measure of board effectiveness. We believe that regulators will benefit from reviewing the findings on board co-option presented in our study and updating board independence guidelines to ensure that the nomination committee conducts proper checks to explore the social or professional ties between newly appointed board members and CEOs. This will help ensure that board members maintain their independence, ultimately enhancing shareholder wealth.

_keywords_and_concept_mapping_through_thematic_content_analysis.jpg)

_keywords_and_concept_mapping_through_thematic_content_analysis.jpg)